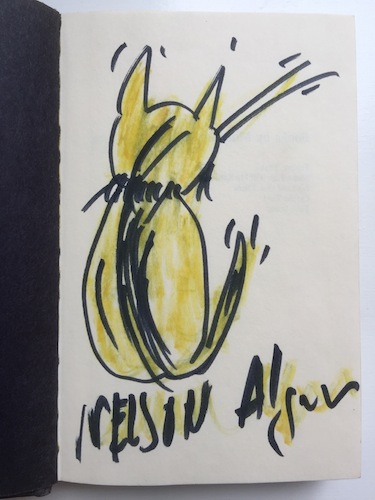

Not long before the recent prison escape that’s been making news, I mentioned to Colin Asher, who is writing a biography of Nelson Algren, that Algren once gave me a copy of Malcolm Braly’s prison memoir. Braly recounts how he broke out of prison one time early in his career as a convicted teenage burglar. The escape was not very complicated, certainly nothing like the break from the maximum-security prison in Dannemora, but it was daring. It also wasn’t long before he was caught. Algren liked the book so much he even signed it for me with one of his characteristic cat drawings.

!['A Memoir of San Quentin and Other Prisons,' by Malcolm Braly [1976]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/nelsons-braly.jpg)

The prison Braly escaped from was a famous old California reform school with a deceptively innocuous name: The Preston School of Industry. What it really was, he writes, was “a machine … to confine, control, and, finally waste our youthful energies, since they couldn’t be channeled into useful social priorities.”

Algren didn’t go into detail about why he recommended the memoir to me except to say he thought it was deeply honest and cleanly written. For example, describing the day he first went to prison, Braly notes:

That cold clear morning in the last days of 1943 when the sheriff drove me south to Preston I had no idea I was about to enter another world where the few virtues I did own would be routinely dismissed as defects. … All I carried … was the Oxford Book of English Verse … and folded into this book was a short story I had started in the county jail, naturally the story of my fall, and a list of rules I had formulated to govern my conduct. … The sheriff didn’t warn me I could have worn a dress and it would have been no less damaging and dangerous than to enter Preston carrying a list of rules and a book of poetry.

After his escape went wrong and he was returned to Preston, Braly was confined to the disciplinary unit whose inmates “were locked up alone.” For him “this was an improvement” because he was allowed the use of a library catalogue to order books. They arrived “like precious goods, in chests.” He read Hugo, Dumas, and Dickens, “not so much for their merit,” he points out, “but for the length at which they wrote. I could order five books a month, and I wanted to make sure they would last.” When he was sent back into the regular prison population, he was assigned to another disciplinary unit, “reserved for hardheads and stone fuck-ups.”

I liked knowing it was as bad as it could get and nothing was being held back to be awarded if you were quiet and cooperative. Sucking the Man’s ass bought you nothing. We were denied the hope of small mitigations and I discovered I didn’t care. I realize something of what I gained by managing to stand firm with the hard asses, and this was dear to the rum, the suspect punk, but I also learned there were things more important than the hope of comfort.

I believe it was Braly’s sense of things more important than the hope of comfort that hit home for Algren. Not many years after being released, Braly was on his way to back to prison — this time to San Quentin. He had copped a plea on a burglary charge on the bad advice of a time-serving cog in the justice system, “a kindly and fatherly” but incompetent and careless Public Defender whom he had wanted to please. On the bus to San Quentin, in a chain of 30 shackled prisoners, Braly found himself sitting next to another recidivist, “by an odd coincidence, a writer.” His description of the man conveys the kind of the pathos that I believe also caught Algren’s attention:

Years before, while doing time in a small midwestern prison, he had written and published a novel, a feat which astonished [the authorities] into granting a parole, and he had followed his star to Hollywood, where it had flickered for some years before setting dramatically. “I couldn’t stay off the sauce,” he told me. He was a nervous and intelligent man with pale eyes and a red face. I took him to be around fifty. I had been standing next to him in the bull pen where we shaped up for the Quentin chain, and one of the transportation bulls had walked up to him to ask, “Are you the writer?”

And Gerry had turned with a smile, much as if he had been asked for his autograph, and said, “Yes, I’ve written twenty books.”

Twenty books and thirty-five B pictures later, here he was on his way to Quentin for bad checks. It troubled me. It threatened my faith in the possibility of change. Despite the vast literature which feeds our hunger for positive growth, I had observed that many people did not appear to change. And if I could not change what would happen to me?

Well, as detailed in False Starts, plenty happened. He would spend nearly two decades of his life in prison. But he produced several novels, including On the Yard, which is filled with fictionalized versions of prisoners he knew. First published in 1967 and since reprinted as a classic by The New York Review of Books, the novel drew the kind of praise that even Algren, a tough customer when it came to assessing books and writers, would have approved. Go read Braly. You’ll see why he caught Algren’s attention.

Thank you for this piece.

Very interesting. Thanks for your share.

Regards.Klaas Oost

Lovely piece my friend, I’ll have to put False Starts on my reading list.

As you know, Algren championed several prison writers, most notably James Blake. Blake was the author of the tremendous, confessional, funny, sad and sexually explicit, The Joint. Algren helped edit that book, and found Blake an agent and a publisher.

A few sentences from The Joint are enough to understand Algren’s interest: “I’m sharing a cell now with a young cat sentenced to the chair for gangbang. He’s a beautiful child, a little solemn sometimes, which I guess is allowable under the circumstances. He asked me what I thought Eternity was like, and all I could offer was a guess–an Olivia de Haviland movie on television…”

At several points Blake lived with Algren, and when he inevitably ended up back in prison he would store his belongings at Algren’s house on the dunes in Gary, Indiana. Algren and his wife Amanda would send marshmallows to Blake when he was in prison because he was missing so many teeth it was hard for him to eat the prison-issue food.

To bring things back to prison escapes: In 1951, Algren and his friend Jack Conroy sent Blake money to finance an escape attempt from a southern prison. The plan went awry, maybe predictably, but Blake made a good attempt and the attempt makes a great story.

Thanks for that. The little-known Blake connection with Algren is fascinating as you tell it. Details like those make me hungrier than ever to read your Algen biography (no pun intended).