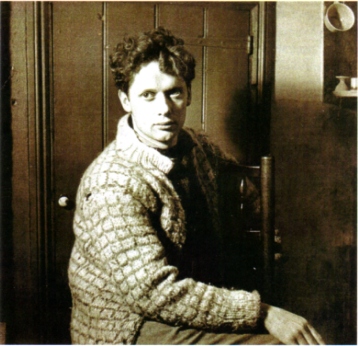

Dylan Thomas, circa 1938

Photo taken at the home of Caitlin Thomas’s mother, Yvonne Macnamara, in Ringwood, Hampshire.

© Nora Summers / Jeff Town / Dylans Bookstore

(The investigative aspect of the essay involves Williams’s indignation over “the cultural theft of Thomas’s identity by a famous imposter” — namely Bob Dylan — which is hinted at in the subtitle: “An Essay on Poetry and Fakery.”)

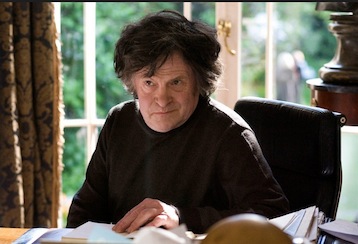

I also claimed that the memoir was infused with “a private tenderness that defies and surpasses moral abstraction.” And now that the published book (illustrated with rare photos like the one at left) has arrived in the mail, I’ve re-read it — and it pleases me to report that the “genuineness of feeling” I claimed for it remains as fresh and affecting as it was in pre-publication page proofs. See if you don’t agree.

Here’s the way Williams begins:

Williams writes that “the promised outing” took place on a Saturday — August 11, 1951 — in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Lecture Hall:As a reward for my having learnt William Blake’s poem ‘Tyger, Tyger’ and for having precociously recited it to him without stumbling, my father promised to take me to hear Dylan Thomas reading at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

I was nine. “Your treat,” he said. “He’s a poet. He’s Welsh.”

He was in the habit of taking me to things that he considered to be “improving” events such as Emlyn Williams’ one-man show based on Charles Dickens’ public readings; or to Shakespeare plays at the Old Vic, and from my earliest childhood my father encouraged me to learn and recite poems.

At his behest I was urged to learn a lot of Blake by heart and most of Kipling’s ‘If.’ I learned one of W.S. Gilbert’s ‘Bab Ballads’ (the one about cannibalism), Gray’s ‘Elegy,’ W. E. Henley’s ‘Invictus’ and a few scraps from the Welsh epic, The Mabinogion, of which my father had a fine copy with a gold embossed cover.

He’d also demand that I’d join him in reciting the seasonal, “It was Christmas Day in the workhouse/the one day of the year/In came the workhouse master/his belly full of beer …” as well as that lengthy music-hall standard ‘Albert and the Lion,’ a narrative poem that ends in tragedy thanks to a small boy at Blackpool Zoo having been somewhat too curious about the zoo’s star attraction, an elderly lion called Wallace.

My father and I found our way to the front of the audience and we sat down directly beneath a small, plump man with curly auburn hair, a raffish bow-tie, loud checkered tweeds and a shining face who stood patiently behind a wooden lectern a few feet above us.

I remember that he seemed not to be able to hold himself still and he swayed gently from side to side as if caught by a rough sea-breeze. I was almost immediately below him. From my perspective, he was spasmodically hidden behind a large pint glass of amber-colored liquid from where he would tantalizingly slide in and out of view.

This human metronome, seemingly set to some slow internal beat, shuffled his slightly soggy handwritten papers and then, after a brief introduction from the museum’s curator, Dylan Thomas sprang to life.

He pitched into a series of unstoppable recitations. His eyes bulged and his voice resonated, boomingly and rhythmically with a series of florid arias spilling out of his diminutive frame. (A phenomenon which was accompanied by misty sprays of saliva that I remember my father found hard to forgive.)

Dylan was so possessed that I thought he might go off like a bomb with his fizzing and surging. I’d not seen anyone drunk before and he was clearly drunk but he was also a phenomenon, as drunk on language as on alcohol. He was caught up by great muscular waves of language – anthemic, torrential and spell-binding – whose meaning was lost on me but whose effect was hypnotic.

I’d been to the Albert Hall once and I’d heard that building’s enormous organ with its golden pipes that so dominate the hall’s interior and I remember that I’d compared Dylan Thomas’ voice to the sound of it when my father asked me afterwards what I’d thought of Dylan’s performance.

I can only recall one line from the reading with any certainty, ‘I see the boys of summer in their ruin …’ I particularly remembered it because my father would repeat it over the years. Whenever it looked to him as if I was going off the rails, he’d trot out this line, to my chagrin as he’d quite spoil it by giving it a stern, judgmental almost taunting edge.

After Thomas’ reading was over my father and I filed out of the auditorium and my father brought me home, announcing to my mother in a matter-of-fact fashion, “The boy was hypnotized,” which was true. I still cherish a vivid, dreamy sense of having been entranced. Rhapsodically entranced.

Evidently I’d not kicked my feet in the air out of boredom once and so, to my father’s relief, I’d needed no chastening, but instead I seem to have surrendered myself to that great organ of a voice which Dylan possessed and I’d remained entirely still throughout. There’d been no microphone in the venue. It was just Dylan’s voice from a few feet away. It was not a wholly Welsh voice. It was certainly Welsh in its impassioned soaring, but it was a voice that had by now mutated into a highly stylized theatrical projection housed within what’s called ‘Received Pronunciation,’ or more frequently ‘BBC English.’

Thomas was certainly aware of his slightly managed magniloquence and he was happy to milk it to maximum effect, whilst at the same time poking fun at himself: deprecating what was something of an assumed, actor-ish persona with the sobriquet “Lord Cut-Glass.”

My father also apparently told my mother (my mother would later tell me) that although I was “hypnotized” I couldn’t possibly have understood a word of what Dylan Thomas had been “on about” since my father hadn’t understood much, if indeed anything at all. He’d say gruffly, “None of it meant much to me.”

He was aware that Dylan was in some way “modern” but I think that he may also have had an uneasy feeling that his fellow Welshman was letting the side down by being, as he clearly thought, quite so wilfully obscure. However my father’s strictures were of no avail, the damage was done, and a potent seed was planted.

When it comes to Dylan’s death, Williams sets the record straight for those of us unaware of a recent examination of the matter: “The received wisdom is that Dylan died as a result of a drinking bout at the White Horse Tavern in New York, but the story’s authenticity has lately been undermined.”

For a start, the post-mortem revealed no signs of alcoholic damage to the brain and nor was there any cirrhosis of the liver. It now seems likely that the real cause of Dylan’s death was medical negligence. Four days prior to his death a New York doctor, a Dr. Feltenstein, gave Dylan an unusually high dose of morphine as a sedative.

Although, while he was staying at the Chelsea Hotel in New York, Dylan had boasted […] “I’ve had eighteen straight whiskies. I think that’s a record,” it turned out that Dylan had, in fact, drunk nothing like that amount and that, rather than his suffering from a colossal alcoholic assault on the brain as the legend favors, he was actually suffering from a severe chest infection, probably bronchial pneumonia, possibly undiagnosed diabetes, and he was experiencing extreme breathing difficulties as a result of one or other of these two conditions rather than from an alcoholic stroke, the received wisdom.

Dylan had suffered from bronchitis and asthma since childhood and his Chelsea Hotel crisis required to be treated with antibiotics rather than with the paralysingly high doses of morphine that Feltenstein would give him on three visits. Feltenstein injected 30mg of morphine, three times the normal dose for pain relief. […] [I]t’s now thought that Dylan’s mistreatment with morphine by an incompetent and flamboyant doctor accentuated his respiratory problems and brought on the coma from which he would never recover.

Finally, a note about the book as an artifact. It is a unique production, as all Cold Turkey Press publications are. Book collectors I’ve met know this about Cold Turkey, and they especially value that. I’m not a book collector in the strict sense of the term — not, for example, the way Jed Birmingham is. But I do value books and I do collect signed copies of authors I’ve known who’ve been kind enough to inscribe them for me. So when I say that both the look and feel of this book tempt perfection, I say it as a layman. But I believe that specialists will appreciate the production as much as I do. The 15 pt. Bembo typeface, the large trim size (260x200mm), the quality of the paper stock (170 grs, cover 300grs), the rare photo illustrations — all of that contributes handsomely to the pleasure I felt.

Postscript: June 3 — I’ll be posting some of the meaty reasons for Heathcote Williams’s contempt for Bob Dylan, and here’s one of the meatiest:

Unlike Dylan Thomas who never once sold out – who never ‘shilled’ for anyone – his deadly Doppelganger would prove as keen as mustard to have his voice serve any and every American corporation.

Well, maybe you´re right -after all nobody´s perfect, nor even Dylan (Bob)- but…that has nothing to do with

his talent