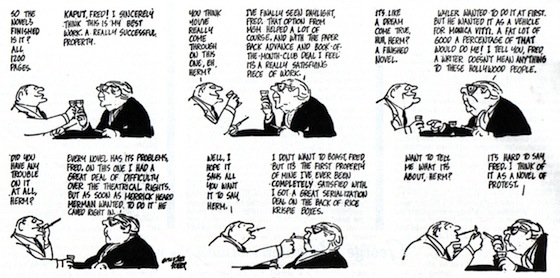

I prefer the Wyler lampoon by Jules Feiffer in a cartoon strip that ran in the debut issue of The New York Review of Books. (The contents of Vol. 1 No. 1, published Feb. 1, 1963, are pretty fabulous: F.W. Dupee on James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time; Mary McCarthy on William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch; Norman Mailer on Morley Callaghan’s That Summer in Paris; along with other reviews by Gore Vidal, William Styron, W.H. Auden, Susan Sontag, Dwight MacDonald, John Berryman, an essay by Elizabeth Hardwick, poems by Robert Lowell, Robert Penn Warren, Adrienne Rich … OK, I’ll stop there.)

By dropping Wyler’s name into a cartoon strip in The New York Review of Books, Feiffer tells us something about Wyler’s status in those days, especially when he’s mentioned in connection with Monica Vitti. (As coolly sexy as they come but not big box office, she was the thinking man’s arthouse actress: three Antonioni films — bang, bang, bang: L’Avventura, La Notte, L’Eclise, ’60, ’61, ’62 — and another for Pasolini.) Maybe the anti-Wyler screed hadn’t congealed yet. Or if it had, it hadn’t clouded Feiffer’s judgment. The fact that he names Wyler to send up “these Hollywood people” is a putdown to cherish.

Wyler often made light of the criticism that Sarris engendered. He could afford to. In France, where auteurist theory originated, Wyler was fêted at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival as one of the world’s five most distinguished directors, alongside Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, Luis Buñuel, and René Clair. But it’s clear the criticism pained him. You can sense that from his remarks when he was honored by the American Film Institute, in 1976, with its Lifetime Achievement Award.

Wyler quipped that in his retirement he had taken up making home movies. “It’s a case of a professional turned amateur,” he said. Unfortunately, his family showed “no appreciation for the out-of-focus and overexposed shots that would make some critics jump for joy.” In other words, if anyone missed the joke, he had become something of an auteur.

One of the grandest ironies in all of this is that Wyler’s belief in commercial success, for which he was pilloried, is no different from the view of that ur-auteurist Orson Welles. As Diane Jacobs correctly noted in her Talent for Trouble review, Wyler “was not content with even his best movies … unless they made money.” Now we see, according to a new book edited by Peter Biskind, My Lunches With Orson: Conversations Between Henry Jaglom and Orson Welles, that that’s what Welles believed. “Essentially,” he told Jaglom, “I don’t believe in a film that isn’t a commercial success. Film is a popular art form.”

![Jules Feiffer [photo: Suzanne Dechillo]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/feiffer-209-e1373895848512.png)