This brings back memories …

One morning there was a knock on the door of my room in the Tenderloin. It was Huncke coming to say good-bye. This was during the late-’60s. He said he was leaving town and could use a loan for the road. If I could spare 25 bucks, he’d be grateful. I didn’t know him well, but he was always cordial, and I was pleased that we were friendly. We sometimes spent a couple of hours gabbing in Janine Pommy Vega‘s tiny North Beach pad, where the two of them lived for a while not far from my job at City Lights. I never expected repayment, of course. Hell, I considered it an honor that he put the touch on me.

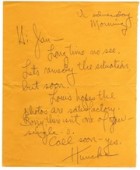

Many years later — it must have been in the mid-’70s — I saw Huncke again in New York at Books & Co., the Madison Avenue brainchild of Burt Britton on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. He was with his compadre Louis Cartwright, who was taking photos, as I recall. Huncke must have sent me some of them, because not long afterward I got a note from him saying, “Long time no see. Let’s remedy the situation but soon. Louis hopes the photos are satisfactory. Sorry, there isn’t one of you single-o. Call soon — yes.”Regrettably, we never did get together. But in 1990, six years before Huncke died, I was asked to review his autobiography, Guilty of Everything, for The New York Times Book Review. I don’t know whether he ever read what I wrote. Hope so.

GUILTY OF EVERYTHING* The small press was Cherry Valley Editions.The Autobiography of Herbert Huncke.

Foreword by William S. Burroughs.

Illustrated. 210 pp. New York:

Paragon House. $19.95.

Given Herbert Huncke’s multitude of crimes, “Guilty of Everything” is an appropriate title with a faintly sardonic ring to it. As a triple threat — narcotics addict, gay hustler and petty thief — at times Mr. Huncke became a pariah even to friends who were outcasts themselves. During a stretch in Dannemora State Prison in New York, he recalls, “not one person in a period of about five years so much as sent me a penny postcard.” For all that — or precisely because of it — Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac declared him innocent of something. They placed him at the heart of the Beat mythology (though Neal Cassady made by far the greater legend). Kerouac claimed to have borrowed the very term “beat” from Mr. Huncke, while Mr. Ginsberg regarded him as the prototypical hipster, a seminal figure of alienation and suffering, more sinned against than sinning.

Unlike Harold Norse’s recent “Memoirs of a Bastard Angel,” which covers some of the same subterranean territory, Mr. Huncke’s autobiography does not breathe literary gossip on every page. Nor does it possess anything resembling Mr. Norse’s graceful prose or fastidiousness. It reads like an oral history of urban survival and offers an uncommon tale of the streets from which the 75-year-old author is lucky to have emerged.Herbert Huncke arrived in New York at the beginning of the 1940’s, already an addict who had been hooked on heroin for the first time at the age of 15 in Chicago. He headed straight for Times Square and, when not in jail over the next decade or so, made 42d Street his headquarters. A sparrowlike man of astonishing endurance, Mr. Huncke became a ubiquitous figure in the midtown tenderloin, darting through its hidden alleys and hanging out with such colorfully nicknamed grifters as Russian Blackie and Detroit Redhead.

In 1946 he met William S. Burroughs, who turned up hoping to sell a shotgun and some morphine. Although Mr. Huncke initially distrusted the future author of “Naked Lunch,” suspecting him of being an F.B.I. agent, they were soon injecting morphine together. “I gave Burroughs his first shot,” Mr. Huncke writes. Through Mr. Burroughs, he met the other future luminaries of the Beat Generation and became, in the words of Mr. Burroughs’s biographer, Ted Morgan, “a sort of Virgilian guide to the lower depths.”

During the good times — to stretch a phrase — Mr. Huncke dealt drugs to support his habit, forged prescriptions, broke into cars, burgled apartments and turned tricks. He also shipped out briefly as a merchant seaman in what seems to have been his only legitimate occupation besides recruiting interview subjects for Dr. Alfred Kinsey, the sex researcher. During the bad times, he wandered the snowbound streets of Manhattan with “shoes full of blood,” as Mr. Ginsberg subsequently described him in “Howl,” a harbinger of today’s homeless legions.

Recalling the harsh winter of 1948, Mr. Huncke writes: “I lived in cafeterias and slept in all-night movie theaters, trying to stay away from the cops on their beats. . . . I’d walk the underground tunnels down around Penn Station, into the station restrooms, nodding on toilet seats. . . . Sometimes I’d roll a stray drunk, maybe steal a suitcase . . . anything so I could make it till morning. . . . I only wanted a place to live or die in out of the cold; not to be found a corpse crouched in a doorway.”

It is a mind-bending irony that he now longs for the old days, lamenting the increased sordidness of the current drug scene like any New Yorker complaining about a decline in the quality of life. He not only recalls when a dapper addict “used to be a role model” — an ethos that apparently has gone to hell — but he wonders, “What’s become of the enthusiasm, the interest in doing new things, in trying to further mankind?”

For the record, “Guilty of Everything” is largely a rewrite of “The Evening Sun Turned Crimson,” Mr. Huncke’s collection of autobiographical vignettes published a decade ago by a small press.* Some of the stories about his Chicago childhood, his Times Square experiences and the counterculture poets of the 60’s have been streamlined or eliminated, while new narrative material has been added to create a memoir with more drive and cohesion.

Although too many details of Mr. Huncke’s life remain maddeningly vague, this is an honest book, as Mr. Burroughs notes in the foreword, and “never more entertaining than when recounting some horrific misadventure.” There is no lack of those.

Postscript: July 23 — Walter Hartmann, who recently translated Carl Weissner’s Death in Paris into German, writes in an email:

me, of crs i’ll nevaire forget his “i’m more than a junkie” when handing him books to sign in a side room apres the hamburg pudel club reading –– someone had just remarked, “this guy did the cover!” when i handed him the ch.valley “crimson” book w/ my garish wrap –– & now someone retorted, “yeh, and junkie and a half!”, & everyone laughed –– i look it up now, the date besides his signature is 11-1-94 –––

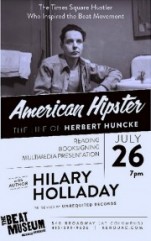

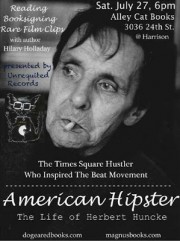

![American Hipster: A AMERICAN HIPSTER: A Life of Herbert Huncke, The Times Square Hustler Who Inspired the Beat Movement' by Hilary Holladay [Magnus Books, 2013]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/huncke-AMERICAN-HIPSTER-cover-e1374547504677.jpg)

![The New York Times Book Review [June 10, 1990]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/huncke-nyt-bkrvw560-e1374531452685.jpg)

!['Guilty of Everything, The Autobiography of Herbert Huncke' [Paragon House, 1990]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/huncke-guilty-of-everything.jpg)

!['The Evening Sun Turned Crimson' by Herbert Huncke [Cherry Valley Editions, 1980]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/huncke-evening-sun-turned-crimson140.jpg)

Hilary’s book is interesting. Thanks for mentioning us.

Hi! Why not add this review to the Amazon Book reviews? It might result in someone being intrigued enough to buy a copy.

I have no connection to Amazon (in fact, I’m just shy of being completely contemptuous of their operation), so the shrill factor here is zero.

Be well.