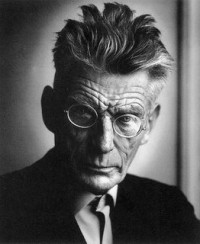

I knew my friend Bill Osborne and Samuel Beckett had met and spoken about Osborne’s musical settings of Beckett’s plays. But I had never heard the details. Now at last the full story!

By William Osborne

I spent seven years doing nothing else but setting the works of Beckett to music. At the end in 1987, I gathered up all the scores and some recordings of them I had, and dropped them into the mail box of his Paris apartment. I knew he was a recluse and a bit of a misanthrope. I figured I would never hear from him and just forgot about it. A few weeks later I got a short letter in the mail. It was with a bunch of junk mail I was going through and quickly tossing away. The letter was in such a scrawl and not very long, so I thought it was nothing and was about to throw it away when I noticed the signature on the bottom: Samuel Beckett.

He said he “liked my work and its execution.” By “execution” he meant performance. He felt that his works should not be interpreted but merely executed. He also didn’t like the way one of the works was performed on the tape I gave him, so saying it was an execution also reflected Beckett’s usual word play. He added that if I were ever in Paris he would like to meet me.

Naturally, I quickly found a reason to be in Paris.

We sat in a café across the street from his apartment and talked for exactly an hour. He always met people in that café instead of his apartment so he could get up and leave if he didn’t like them. He was wearing a big overcoat and didn’t take it off so I figured he would quickly leave, but he seemed to enjoy our discussions. From time to time he would unbutton a button on his coat. His coat was mostly open by the end of our visit. I wondered if people judged the success of their visits by how many buttons he undid.

We talked about a wide variety of things. He was interested in tennis and wanted to know more about Boris Becker since I live in Germany. I knew he liked Schubert songs, so I gave him a set of recordings of Winterreise done by Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten. I asked him if he knew the recording. He said he didn’t. He seemed elated with the gift and practically grabbed it out of my hands. We talked about his time with James Joyce. He seemed to really enjoy reminiscing about that time.

(I might add that the reason I gave Beckett the Pears/Britten version of Wintereise wasn’t just because I figured that he would have long had the definitive Dieskau recording, but even more because Joyce had a thing about Irish tenors and Pears leans slightly toward that lighter, brighter style of singing (even if still not much like one.) I seem to remember that Joyce occasionally drug Beckett to performances of one of his favorite tenors. My thought was that Joyce might have influenced Beckett a bit in that direction, and that he might appreciate Pears’s style. I also think Beckett was interested in the theater scene in the UK to which Pears and Britten made significant contributions. For whatever reason, Beckett was clearly very curious about the recording.)

Beckett was always a stickler for not allowing any changes to his stage directions, and he took an even dimmer view of things like musical adaptations but he was fairly tolerant of my efforts. He said he did not like musical settings of his work “because the music always wins.”Until I read your latest blog, I didn’t realize that line had such a history. The concern is just a practical reality. For 500 years Western culture has been trying to create music theater that genuinely integrates music, text, and theater, but it has never succeeded. As opera illustrates, the music not only wins, but by miles. For a playwright with Beckett’s meticulous sensibililties, having his words buried under the dominance of music was painful.

Anyway, I told Beckett very matter of factly that I was trying to create a kind of music theater where the music didn’t win. He seemed taken aback and intrigued. My goal has always been to create a complete integration of music, text, and theater where all three elements are of equal importance. We talked about that for quite a while. (There is a long essay on my website where I outline my theories of music theater along with a video to illustrate my efforts.)

Beckett wrote his texts with an extremely refined musical sensibility, which is why I was drawn to them. He expected that his texts would be performed with certain rhythms, but he had no way of notating that, so I think he was often frustrated by productions he didn’t direct himself. In my settings, the texts flow freely between sung and spoken passages, and I precisely notate the rhythms of even spoken passages. I think that is one of the reasons Beckett wanted to meet me after looking at my scores. I felt he wanted to be able to notate the rhythms of his spoken texts. Based on his interest, I think we might have eventually done something together, but this was shortly before his death and his health was already failing.

I spent those seven years setting Beckett with the hope I could learn enough from them to write my own texts. I have been doing that since 1987 which was not long after I met Beckett. Naturally, I could never match even remotely the beauty and meaning of Beckett’s words, and so my works probably began to lean more toward music. It’s really hard to keep the music from winning, and that has profound existential meanings almost no one understands. Anyway, your blog brings back many memories for me that are almost like from another life, but I’m still trying to keep the music from winning.One other little thing … In return for my gift, Beckett wanted to give me tickets to a performance the next night of Madeleine Renaud performing “Oh les beaux jours!” in Paris, but I had already booked my return flight to Munich. I still regret not going. I should have just bought another airline ticket.

This is a slightly edited version, with illustrations added, of a comment Bill made two days ago on the blogpost “An Absurd Debate About the Last Word.” I thought the comment deserved more prominence than as a mere appendage. — JH

![Notation from score for Osborne's musical setting of Beckett's 'Happy Days' [1987].](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/winnie-page-6-small-copy.jpg)

Thank you for this, Jan. You are too kind. The “Samuel Beckett Meets William Osborne” is hilarious.

One more typo to clean up: In the caption under the video link above–to Abbie performing as “Winnie”–her last name should be “Conant.” I think Bill would know that, biergarten visit or not. 🙂

Done. Thanks for the catch.