I emphasize literary. Although Perlez rightly describes the novel as “a scathing portrait of the imperious attitudes of the British” colonials who once ruled the country now known as Myanmar, it is most affective literarily as a portrait of its touching central character, Flory. He is a tragic figure who could have stepped out of the pages of a Joseph Conrad South Seas novel written from the point of view of the British Raj.

In her article about an attempt to preserve the house Orwell lived in in Katha, Myanmar, “camouflaged in the book as Kyauktada,” Perlez gives an apt summary of the story, which takes place in a “colonial outpost on the banks of the mighty Irrawaddy River [where] brutish characters swilled too much whiskey at a whites-only club, and wilted in the vaporous heat.”

The snobbery and ignorance of the British overseers in Burma are exemplified by Orwell’s youngest creation, a 22-year-old naïf named Elizabeth Lackersteen who arrives here with her blond hair bobbed into an Eton crop, the mode of the late 1920s, and wearing fashionable tortoiseshell glasses. She comes in search of a husband.

Flory, a British timber merchant with a birthmark down one side of his face, the only character who shows empathy with the Burmese and who despises the boozers and bores of the British Club, falls for her.He tries to interest her in local culture, taking her to a pwe, a Burmese play performed by gaslight outdoors on the street. She recoils at the “smelly natives,” calls most things “beastly” and prefers to laze in a drawing room perfumed by “chintz and dying flowers.”

Elizabeth’s favorite haunt is the British Club, where the men wear khaki shorts and topee hats and berate the Burmese servants for running low on ice for their tumblers of whiskey and gin. …

Elizabeth spurns Flory, who, overcome by desolation and rage, shoots himself. In turn, she is spurned by Lieutenant Verrall, a rude — even by British Club standards — polo-playing young army officer. At the end of the novel, the villain, U Po Kyin, an exceptionally rotund magistrate, moves to another district for a plum job.

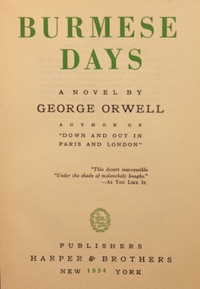

It seems to me no accident that Orwell chose an epigraph for the novel from Shakespeare’s “As You Like It” — This desert inaccessible / Under the shade of melancholy boughs — as if to underscore the literary nature of his project.

![Orwell's house in Katha, Myanmar.[Photo: Aung Shine Oo for The New York Times]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Orwell-house200.jpg)

thanks for promoting this novel, you made it intriguing enough to make me try it. I have never gotten around to reading this, perhaps because I failed to complete “Keep the Aspidistra Flying” and afterwards, pretty well stuck to Orwell’s journalistic side; “Down and Out in Paris and London” is one I re-read often.

most of us have the fortune of wearing our otherness inside of us. I think at certain moments though, it can feel like a birthmark, visible to anyone who see us.

the description of Flory and Elizabeth reminds me that young alienated men almost always fall for the wrong woman at some point, and vice versa to be sure.

thanks again, looking forward to reading “Burmese Days”.

It’s a brilliant piece of novel writing, not journalistic at all. If you don’t like it, I’ll buy you a drink. If you do, you buy me one.

bought it, am reading it and damnit, I think I am picking up the bar tab.