Leonard Cohen, who is not given to easy praise, has called Sinclair Beiles “one of the great poets of the century.” Meaning the 20th century — they met back in the early 1960s on the Greek island of Hydra. Was Cohen being uncharacteristically hyperbolic? Well, William S. Burroughs, also not given to easy praise, once wrote:

The poetry of Sinclair Beiles is distinguished and long distilled; its unexpected striking images bring a flash of surprised recognition. The poems open slowly in your mind, like Japanese paper flowers in water.

You’ve probably never heard of Beiles, not even if you read a lot of poetry. As the title of a recent book from Gary Cummiskey’s Dye Hard Press put it, Who Was Sinclair Beiles? Good question, answered in part by Cummiskey’s probing article-cum-interview. But Beiles was something of a mystery even to those who knew and marveled at him.

Heathcote Williams writes in an unforgettable essay, “Sinclair Beiles: The first poet in space”:

Despite Burroughs’ impressive recommendation Sinclair Beiles often fell asleep during his own poetry readings thanks to a hefty diet of prescription drugs which Sinclair would carry around in a large plastic bag and which were always placed beside him on-stage so as to be within easy reach. This was a pity since Sinclair’s poems, as Burroughs had attested, were worth listening to, once he could be aroused.

Apparently, the better you knew Beiles the more you marveled. Williams continues:

When I first met Sinclair he was living in Paris with a Creole woman who had filed down teeth ending in needle-sharp points. Early on in his life Sinclair would appear like an alert wagtail, always hopping about possessed by new ideas: some new artist he’d met — an exiled Romanian covered in etching ink in a recondite atelier in the Marais whose poems were, in Sinclair’s view, “better than Blake”; Serbian glass-blowers who made crystal balls that were “better than television”; artists in light who would “open up your Third Eye till you go completely blind and mad but you won’t mind”. He had an eye for the exotic; there was a transgendered Marxist performance artist from Namibia who would recite the Communist Manifesto in Xhosa.

Williams’s essay, originally published in The Raconteur, quotes a letter that Beiles wrote to Gerard Bellaart in 1969, the year before Bellaart launched Cold Turkey Press:

I can’t tell whether I’m cynical or optimistic — whether there is something out there organising a life of pleasure or pain for us. It’s beyond my scope. Whatever happens is meat for my poetry. I record what’s happening. I don’t care why. I haven’t been able to discern any pattern to my existence. I don’t hunger after being part of a total harmony.

![Excerpt from 'Inmates,' in 'The Idiot's Voice' by Sinclair Beiles [Cold Turkey Press, 2012] 'I was in Bowden House, a psychiatric clinic in Harrow suffering from deep melancholy. All the writing I was doing did not seem to relieve it. It devolved around autobiographical subjects of an unpleasant nature. ...'](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/6The-Idiots-Voice1-e1352755092454.jpg)

‘I was in Bowden House, a psychiatric clinic in Harrow suffering from deep melancholy. All the writing I was doing did not seem to relieve it. It devolved around autobiographical subjects of an unpleasant nature. …’ Excerpted from ‘Inmates,’ in ‘The Idiot’s Voice’ by Sinclair Beiles [Cold Turkey Press, 2012]

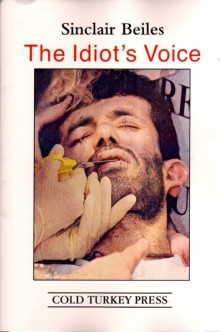

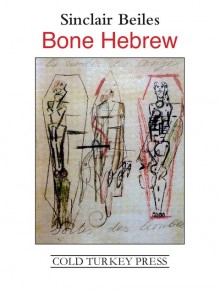

The scarcity of Cold Turkey editions makes it imperative to post an excerpt from The Idiot’s Voice. You can judge for yourself what has inspired not only the forthcoming homage but also a biography being written by the Dutch author Fred de Vries in Johannesburg, South Africa, where Beiles grew up. (Beiles was born in Kampala, Uganda, in 1930, lived most of his peripatetic life in Europe, and died penniless in Johannesburg in 2000.)

Here is a poem from a series, called “Inmates.” You’ll notice it does not depend on dazzling language or rhetorical flourishes. There are no well-turned phrases or brilliant metaphors. Instead the language is plain, sometimes awkward. The poem is rich just the same. It reads like a folktale that tells a story of the sort a Chinese sage might tell. It’s what I like to think of as “poetry for real.”

During the late 1950s Beiles lived for a time at the Beat Hotel in Paris, where he conspired with fellow residents Burroughs, Brion Gysin, and Harold Norse, and with visitors like Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso, to stand the literary world on its head. One major project did. While working as an editor at Maurice Girodias’ Olympia Press, Beiles shepherded the manuscript of Burroughs’s Naked Lunch into print.Furthermore, according to Williams, “Sinclair always claimed that it was thanks to his own acquaintance with the dadaist Tristan Tzara that he was able to introduce Burroughs and Gysin to Tzara’s method of composition, commonly known as ‘cutup.'” Beiles was in fact a co-author — with Burroughs, Gysin, and Corso — of Minutes to Go, a book of experimental cut-up texts published by Two Cities in 1960.

But it was Beiles’s nonliterary revelations that give a truly indelible impression of the man. One, for example, was “that the barren Sahara desert might be set on a much more productive course with the aid of industrial quantities of discarded tea-leaves,” Williams recalls. He writes:

I never met Beiles, but we had corresponded. A mutual friend, Nanos Valaoritis, had put us in touch. Nanos knew him from Athens. He was enamored of Sinclair’s off-the-wall grandeur, both in his writing and his personality. I subsequently published several of Sinclair’s pieces in a little magazine during the late-’60s in San Francisco. I also made plans to publish a book he co-wrote with Annie Rooney, Alice in Progress, under the Nova Broadcast imprint. It was announced in promotional materials. Regrettably, Nova Broadcast folded before that happened.The idea arose as follows: One evening after a meal with his mistress (whose distinctive teeth were invaluable in the maceration of Sinclair’s food — their meals together echoing the erotic meal in “Tom Jones”) Sinclair noticed that something was growing in their window box.

There was nothing unusual in this except for two things: first, Sinclair’s window-box had been filled entirely with sand and secondly, Sinclair’s horticultural attentions had been limited to emptying tea-leaves into it. Yet some form of vegetation was beginning to grow there, despite these inauspicious conditions.

It was when he was hovering above the tea leaves, the sand and the newly sprouted shoots, that Sinclair had his Eureka moment whereupon he began to urge everyone that he met that tea-leaves were the answer to the whole of the African continent’s food shortages.

He didn’t let it go at that. With indefatigable verve he’d throw himself into setting up elaborate presentations … all in the hope of attracting investors who were to be persuaded that limitless acres of North African sand could be composted using Sinclair’s method. Not only were the Algerian, the Moroccan and the Libyan embassies and their trade legations approached but also the Secretary General of the UN, and the Queen of Holland together with Tetleys Teas and Lyons PG Tips who were also all targeted. …

Bellaart, who like Cohen met Sinclair in Hydra, brought out a dozen Cold Turkey books by 1975, all in limited first editions of 250 copies, including Sinclair’s Sacred Fix along with works by Burroughs, Ginsberg, and Williams, as well as Artaud, Cendrars, Lorca, Vallejo, Bukowski, Carl Weissner, Ed Sanders, and Ira Cohen. More recently, and in more limited editions of pamphlets, posters, and cards, the list of Cold Turkey authors has grown to include many others already in the pantheon, such as Beckett, Pound, Arp, Mallarmé, Schwitters, and Céline. But for now it is Bellaart’s special devotion to Beiles that almost alone keeps his gloriously dissident writings alive.

!['Inmates' from 'The Idiot's Voice' by Sinclair Beiles [Cold Turkey Press, 2012]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/7The-Idiots-Voice-e1352750227194.jpg)

!['Inmates' from 'The Idiot's Voice' by Sinclair Beiles [Cold Turkey Press, 2012]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/8The-Idiots-Voice-e1352750763519.jpg)

!['Minutes To Go' by William Burroughs, Brion Gysin, SInclair Beiles, and Gregory Corso [Two Cities, Paris, 1960]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/sinclair-beiles-minutes_to_go.front_.jpg)

Thank you for shining a light on Beiles’ name and work. Both were hitherto unknown to me. “Inmates” is enough of a poem to persuade me, by itself, that I’ll want and need to connect more with the work of Beiles. You’ve done him a service. You’ve done readers everywhere a service.

Glad to be of service, Ron. Much thanks for your comment. I just checked you out. Whoa! You tickle those keys like a magician. And that band of yours sounds magnifico!

I also first heard about Sinclair from Nanos, who showed me some of his poems, which I liked a lot. Then met him, as well as Cohen, in the summer of 1970, on Hydra. I remember Beiles showing up at the house I was staying at in drag, and was, as far as I remember, as wild as he was unpredictable. In that context, Cohen seemed to be a model of sanity.

Fascinating. I wonder if you’re in touch with Fred de Vries. I think he’s eager to speak to people who knew Sinclair. As I say, I never met Sinclair. But I did meet Cohen — twice. The first time in 1963 on Hydra. I had just turned 21 and was a would-be writer. He invited me up the hill to his house. It had white-washed walls, as I recall, and was bare of furniture. Later, in 1972, and totally by chance, I ran into him in Paris, walking by the Seine. It was a foggy night and he emerged from the mist wrapped in a trench coat looking very much like a spy in an Eric Ambler novel. He said he was in town for the CBC on a free-lance assignment to interview some muckety-muck. I doubt he would have remembered me so many years later, but I happened to be with a former girlfriend of his. Surprised and pleased to run into her, he invited us up to his room — he was staying at a little hotel near the corner of Boule Miche and St. Germain — where he immediately broke out his hash stash and lit up a pipe for all of us. I don’t recall the conversation except that he mentioned that “The Favorite Game,” his first novel, would be published soon. I also recall leafing through his copy of his book of poems, “The Spice-Box of Earth,” which he showed me with pride. I had never read it. It was beautiful stuff. When the novel came out, sorry to say I found it a letdown.

Cohen didn’t have any hash when I met him- at the time Hydra seemed a bit paranoid when it came to dope- the Colonels were coming down hard on all those hippies- but he did offer a Mandrax, which I politely declined. I’ve never been to read either of his novels, though I’ve tried once or twice. I sort of have a soft spot for some of his poems, though I don’t know why because I can’t objectively say it stands up to Olsonian tastes. Must be the sentimentalist that lurks inside me. We’d arranged to play some music together, but never got around to it. By the way, how did you meet Nanos? Was it at SF State. I met him there in what must have been his first week on the job. I and last saw him in London sometime in the late 1980s.

Olsonian tastes vs. lurking sentimentalism. Not a bad way to put it. Nanos and I saw each other in San Francisco so often that I don’t recall our first meeting. It probably had to do with the little magazine I was publishing in San Francisco, or with City Lights Books, where I had a gig working as Ferlinghetti’s assistant. But it had nothing to do with SF State. I knew he was teaching there because he almost invariably stopped by my flat on Guy Place on his way home to Oakland. I published some of his poems and prose, including a broadside of “Endless Crucifixion.” You can see it here, along with Andrei Codrescu’s reminiscence of our meetings, and a link to Nanos’s terrific little memoir of his years in London during the 1940s.

http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/2011/04/a_poem_from_the_late_20th_cent.html

The last time I saw Nanos must’ve been 1998 or ’99 in New York, when he was being feted by a high-brow Greek literary society. Regrettably, I’ve lost touch with him. But it was great to see him still kicking last year a month before turning 90. Maybe you’ve seen this?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=maTfvtzOW54

And here he is reading one of his poems in Greek earlier this year.

Thanks for this Jan! Fascinating poetry. Best regards.