Matthias Penzel’s obituary about Carl Weissner, more an appreciation than an obit, appeared this past Sunday in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung. He has kindly translated it from the German for me, and I post it here with his permission.

Penzel, a Berlin-based author of several books, including TraumHaft (a rock ‘n’ roll novel) and Rebell im Cola-Hinterland (a biography of Jorg Fauser, written with Ambros Waibel), says he met Carl when he was starting out as a journalist: “He rolled many balls in my direction, contacts, ideas, door-openers, the whole works.”

This version of Penzel’s obiturary restores cuts made in the published German text and adds a few enhancements. As he explains: “Nelson Algren once said, ‘No book was ever worth the writing that wasn’t done with the attitude that this ain’t what you rung for, Jack — but it’s what you’re damned well getting.’ Same goes for this — ok?”

Mannheim Transfer

By Matthias Penzel

One of the few stories he wrote in German (“Last Exit to Mannheim”)* kicks off with the first-person narrator sitting at the foot of the Bay Bridge, San Francisco, on the stairway of his apartment house fire-escape, clocking the neighbor across the street with an old pair of binoculars (“used to play with Charlie Parker at the Five Spot”) as he watches TV (“an old Hollywood ditty with Robert Mitchum who was once again wearing a pair of underwear way too huge for him”). Just hearing the title of one of Carl Weissner’s books, published years ago, makes contemporary cutting-edge writers like Mark Z. Danielewski sit up and listen — the title in question was The Braille Film (most interesting to a guy whose House of Leaves emulates the syntax of movies and features the scribbled notes of a blind man who happens to be the only person to have watched a certain movie). This may capture it: the story of the life and impact of works by Carl Weissner.

When you phoned him, you would be greeted — for years — by nothing but the shrill pheep of an incorrectly set fax-answer-phone-machine. When he insisted on driving you home because of atrocious rain at six in the morning — his glasses finger-thick — doing 18 mph on the highway, in the right lane at least — and then when you awoke from nightmares, when letters were returned unopened, because the mailman — working a Mannheim neighborhood of Turkish gambling parlors — didn’t see the name-tags on the door bells, which would have led him to a letter box inside Carl’s apartment block across from a Women’s Bookstore, then you would sometimes ask yourself: Was ist hier bloß los?

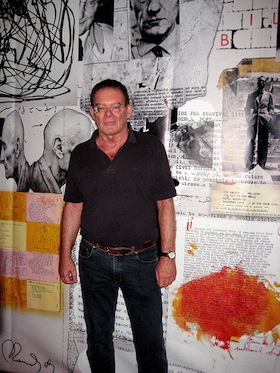

Carl Weissner translated books. While he tried pretty hard to remain in the background and unreachable, he is known to people in the weirdest hangouts — in Calcutta just as much as in Luxemburg, at City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco, among Bukowski readers worldwide anyway. If you mentioned to him that underground poets from East Germany or ad writers or celebrity reporters in Hollywood would scream in awe, “You know Carl Weissner!?!,” he would only shrug and react with a smile. Impenetrable. How does someone grow up as a child during the war, amidst the rubble, and learn to be gentle? Someone who looks and listens, who goes way beyond fine manners. A good boy at the piano who discovers jazz, then with a grant goes off to Manhattan and ’68 San Francisco. And then becomes, in still grey and triste Germany, the expert for hipster slang.

His translations are actually exactly that: transfers from a different world, interpretations into a language, a country, in which — as he put it — “many understand ‘Schriftstellertum’ like an employee, right in the midst of a streamlined career — never to wrong-foot or make a mistake, but rather to function straight and reliably.”

After the war, performing with and for GIs in Karlsruhe, he would play in jazz bands, gobble up special editions of the Times Literary Supplement, and wanting more from life, start to write. Letters. Up to twenty a day. To legends of the counter-culture, John Sinclair, Burroughs, Ginsberg, the dramatist Mohit Chattopadhyay in Calcutta, beatniks in Greece, Mexico; at the same time to Wolf Vostell; and as he could not afford all his own reading material, he cobbled together a magazine, in which he would print this New Internationale. Like a pretty cool agent, or rather a dealer, he would translate J.G. Ballard, the Beats, Warhol, Dylan, Leonard Cohen — but also Will Eisner, Denton Welch, Diane Arbus, Muhammad al-Murabit — into a German that had not existed before. The man who stayed in the background thereby kicked open a door to a library, existing invisibly and parallel to what every well-educated literary student had been completely unaware of, a door to a world of books, to grooves and a language that pulsated with life.This he did with an active vocabulary that made some of his translations — another silent smile here — look even better than the originals. And because he was a pro at his craft — never too self-assured, always with open ears, wide-awake vision, and with AFN radio playing in the background. He translated books — and did well, not grand — many of which got reprinted, repeatedly. Ten hours a day in the early days. The gain, in terms of merit not earnings, was that Weissner helped knock the mildew of past decades out of the German lingo. Zappa, whom he also translated, has by now had streets named after him; Dylan is touted as a contender for the Nobel Prize — yeah, sure (so what). Weissner remained unobtrusive. Ten years ago, he quit what he called his “day job.” Kept listening, looked around, and wrote. In Thailand, Paris, in Marseilles tracing Rimbaud, then back into the shadow of the Empire State Building. Finally, at the age of 70, he found a home for his own novels — Milena-Verlag, in Vienna — which he had nearly given up hoping for. Also his latest book, only months old, seems to be taking a whole new generation of readers on a trip.

Despite all his raging against contemporary German writers whose “A-level essays” are very neatly written but god-awful to read, he never ceased to rave not only about friends like Jürgen Ploog, Jörg Fauser, and Patrick Roth, but also about Anna Katharina Hahn, Christoph Ransmayr, Marie-Luise Scherer. Yes, he was always switched-on, curious. Talking about Jack Bauer, criticizing The Wire, talking about Grindcore Metal and Schopenhauer, skaters in Venice Beach. Inscrutable. Then mumbling, en passant, a few lines by Adam Green, thoughts on cyberpunk and SMS-texted novels — and this was years before he would go to Karstadt Mannheim to have the pre-paid card of his mobile phone recharged (by assistants who would gather around him to catch a glimpse of that darn antiquated phone), before he would exchange his fax-phone machine for a PC with access to the internet, and remain stuck to the old spelling rules.(He insisted he would not write according to the new rules taken up by news agencies and most German media around 1998. He would not let them change his work. In other words, in some ways he was quite conservative, stubborn you could also call it, operating on principles, whatever. Or simply somebody who was clear about what he wants and what he does.)

Yeah, letting the talk do the walk, his own books capture the way he thought and talked and wrote: They brim with life, they are whole reference systems that lead to much more than what is on the page. The narrative still has traces of that first-person narrator at the foot of the Bay Bridge, waiting for City Lights’ Ferlinghetti and, incidentally, Claude Pélieu, who wrapped his prose in truly cool lingo. The narrator watching what the other guy is watching, noticing and declaring what we always felt but hardly dare say. Was ist bloß los? what’s the story here? One take would be to say it is like the exploding Cadillac on screen, like the labyrinth in The Braille Film: an expansion of senses and sensibilities in order to look into the world with new eyes . . . the other take somewhere between the sheer force of cascading information and the charming effect of matryoshka dolls, image within image all the way to the meltdown, where — as in the finale of his final novel, Die Abenteuer von Trashman — the cuts are flickering while “curls of celluloid with nothing left to see on them chirrup out of the projector.”

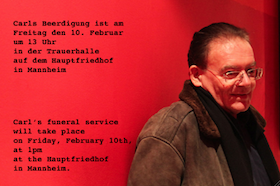

On a Tuesday in January 2012, Carl Weissner was found dead in his flat in Mannheim. I’ll bet anything that we will still get to read a hell of a lot by him — and that the old stuff will keep rockin’ for a long time. Unbeatable basically. Told in a wacko but straight manner. Like a shot, intravenously. The sorta stuff that makes you long for a reliable dealer of your choice.

*published in Gasolin 23, first issue, i.e. #2, 1973