Paul Newman, who died at 83, once told me in an interview, “There’s a part of me that has always wanted to win an Oscar when I’m 83, so I could say, ‘So there!'” The interview took place in Boston, at the Meridien Hotel. Newman was 57 then and in top form, promoting “The Verdict.” He starred as an alcoholic Boston-Irish lawyer, and there was the usual Oscar talk. The script, written by David Mamet, called for him to play the role as a piece of bruised human wreckage who has sunk so low he’s become a deadbeat ambulance chaser. Bleary-eyed, he searches the obituaries for notices of accidental deaths. Then he lines up with the mourners at the funeral service and drops his card in the widow’s lap.

Newman didn’t win the Oscar that time. (He won four years later, for “The Color of Money.”) Anyway, his death on Friday reminded me of the interview. Rolling a toothpick from one corner of his mouth to the other, he sat with a half-eaten hamburger and a side of potato chips in front of him on the coffee table. The hallway outside his suite was lined with reporters hoping to get a few minutes with him. “It’s like double parking in front of a cathouse,” he remarked, genuinely amused.

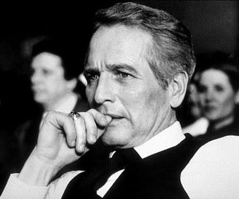

In contrast to his role in “The Verdict,” Newman didn’t have a blemish on him. He was lean, tan, and svelte in his tight brown slacks, knitted maroon tie and button-down shirt. He looked so handsome that the tinted glasses on the bridge of his nose, although meant to shield him from stares, merely served to heighten his glamour. I asked him how he had managed to look like such a dissipated wreck in the movie. Even his voice sounded wrecked. He answered with a quip: “You eat gravel for breakfast.” But Newman was not a wit, and he knew it. He compensated by being alternately blunt and playful. And always a bit defensive.

Earlier that morning he had faced waves of group interviews with as much dignity as could be expected. One reporter had asked him, “Do you ever wish you were born with brown eyes?” It was the sort of question likely to turn him surly. But he cracked wise in a tone earnest enough to convey sympathy rather than contempt for his questioner. “There is nothing designed to make somebody feel more like a piece of meat,” he said, “than some chick coming up and saying, ‘Take off your dark glasses because we want to take a look at your baby blues.’ People wonder why I get offended by that. What if I said to her, ‘Gee, you’ve really got a great set of tits, honey. Do you mind taking off your glasses?’ I mean, what do they expect your reaction to be? Are you supposed to look soulfully at them? Do I give them just a peek? Or a flash? It’s such a ridiculous position to be put in. As I said to one lady, ‘Sure, I’ll take them off, if you let me inspect your gums.”

The vulgarity of his anecdote, suggesting a horse trade, a dental appointment, and a pornographic invitation, made it Newman’s best crack of the day, though it was almost matched when another reporter asked how he dealt with autograph seekers. “I generally try to puke on their shoes to get their attention,” he said. “It gives them a gentle hint that I’m uncomfortable.”

Paul Newman was one of the greatest actors of the last 50 years. His play was natural, his charm uncompromising, I am sure the women who met him felt seduced by his incredible attractiveness. I wish I could have just melted in his arms.