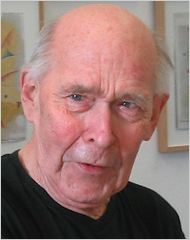

Another old friend is gone. We spent many a winter night together in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, keeping ourselves entertained over a bottle or two. He died in Berlin. He was 81.

Another old friend is gone. We spent many a winter night together in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, keeping ourselves entertained over a bottle or two. He died in Berlin. He was 81.

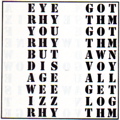

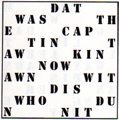

Emmett Williams was a poet who’d mastered “the write of arting.” Here’s an interview worth reading that fills in lots of details about him. And here’s an excerpt from “THE VOY AGE,” which “started out,” he once explained, “as a long kinetic poem celebrating the travels and exploits of Two Buk Tim in Tim Buc Too.” The format is based on a mathematical progression, the words a mere taste of Emmett’s playfulness.

During our time in northern Vermont, after I had succeeded Emmett as editor of the Something Else Press, we taped a long conversation about poetry and art that was later published in the West Coast Poetry Review, in an issue devoted to his work. I asked him if he agreed that he was “a poet before anything else.”

“I agree, with a few reservations,” he said. “The ‘anything else’ bothers me.”

We sat on a rolling lawn beneath giant pines in a high clearing. Jay Peak could be seen some thirty miles to the north at the Canadian border.

“I was a pretty good bartender once,” he went on. “And foreman of a landfill project. I can wield a mean axe in the forest, too. Yes, I’d call myself a poet before anything else, though I wouldn’t call it my occupation. Call it my preoccupation. Making poetry is the thing I’ve always done, or wanted to do, whatever else I was trying to accomplish. The thing that interrupts whatever else I’m doing. A ‘disturbance’ that I can’t tune out.”

I said he made it sound painful. “I know,” he said, “I’m very romantic about it.” He continued:

I see no practical reason whatsoever for making poetry or art. But that’s what I do, and there must be a reason for it. I wrote a spooky poem about it once, about this disturbance, how it was like the sound of a baby crying somewhere, you don’t know where, and nobody else hears the crying, but you feel compelled to look in every room, comb the fields and forests, and you never get to the source of the sound. Something deep down inside that pushes you on full speed ahead even though you don’t know where you’re headed. And the poem, or painting, or whatever, is a by-product of the search. It sounds melodramatic, I know. But face it, it’s something of a curse. The curse of Erato. Say, that’s a good title!

I pointed out that his love poetry was peculiar. In one love poem, for instance, he substituted “objects and activities for the letters of the alphabet.” According to the documentation of a performance in London, “the word ‘love’ could have been spelled the smoking of a cigar plus blowing a silent dog whistle plus eating a chocolate off the floor like a puppy plus tooting a little ditty on the flute.”

I pointed out that his love poetry was peculiar. In one love poem, for instance, he substituted “objects and activities for the letters of the alphabet.” According to the documentation of a performance in London, “the word ‘love’ could have been spelled the smoking of a cigar plus blowing a silent dog whistle plus eating a chocolate off the floor like a puppy plus tooting a little ditty on the flute.”

But “read on,” he said. “It says that during the Darmstadt performance it could have been spelled peering at the audience through a hole in a piece of paper plus offering a cigar to a girl plus extracting an egg from a portable vagina plus covering my eye with a patch. And so on.” He continued:

The poem is as depersonalized as the letters of the alphabet the twenty-six objects and activities are substituted for, and using an alphabet of objects and activities to spell “love” or anything else is bound to produce combinations that go far beyond the barriers of logic and common sense. Chance encounters make strange bedfellows.

How come he didn’t call the poem a Happening? “I call it a symphony,” he said, referring to the title ALPHABET SYMPHONY, “though it’s a poem, of course. A poem that gets off the page.”

If the idea of transposing one set of symbols into another was essential to his poetry, or at least some of it, so was a compulsion to make pictures. “Why does a poet make pictures?” I asked.

![EMMETT WILLIAMS, 1975 [Photos: Jan Herman (courtesy of Northwestern University Library)]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/hermanWilliamspics%20260.jpg) “Something Kandinski said years ago about his own poems is as good an answer as I could give, to the effect that writing poetry was for him simply a ‘changement d’instrument,’ and that the driving force behind all his work — paintings or poems — remained always the same. He was a fine poet, you know, only most art historians are too busy with the pictures to bother with the poems.”

“Something Kandinski said years ago about his own poems is as good an answer as I could give, to the effect that writing poetry was for him simply a ‘changement d’instrument,’ and that the driving force behind all his work — paintings or poems — remained always the same. He was a fine poet, you know, only most art historians are too busy with the pictures to bother with the poems.”

Emmett made a living through the sale of his lithographs and prints, as well as by teaching. But, “one thing I’d better say right here,” he said:

I consider myself a Poet, capital P, without any qualifiers. Not a concrete poet, not a visual poet, not a veri-voco-visual-something-or-other poet, just a plain poet. But a poet who has found his expressive form in some untraditional ways of using language, of using it as raw material. My methods are closer to composing and painting and sculpting than to the methods of most other contemporary poets. I can write sonnets, too, and I have a fairly large body of more or less traditional verse, but that’s not what interests me. I feel much more at home in the restricted landscape of “programmed” books like SWEETHEARTS or THE VOY AGE. Maybe restricted is a misleading word. I mean it the way Paul Valery uses it, where he says that the greatest freedom comes from the greatest strictness. I don’t like to run off at the mouth in poems. I do that all day long. I’m not a diarist, or a politician, or a hysteric, or an analyst, or merely a recording instrument. A poet is a maker, a creator, and I take that literally.

The conversation went on like that, running off at the mouth for more than 20 pages. It touched on all sorts of subjects, from his early career in Europe as a feature reporter at the Stars and Stripes, to the artists and writers he knew and admired and whose work influenced him — Diter Rot, Brion Gysin, Daniel Spoerri, Robert Filiou, Jean Tinguely, Claes Oldenburg, Richard Hamilton, Ay-o, Wolf Vostell, Claus Bremer, Hansjorg Mayer, Jackson Mac Low, Jerry Rothenberg, David Antin, Dick Higgins, John Giorno, Ian Hamilton Finlay — to his interviews with Ezra Pound, to his Kenyon College days as a student of John Crowe Ransom.

“I went to school with Tony Hecht, and James Wright, and William Gass,” he recalled. “And so what. It’s really irrelevant. There are a lot of people on the planet, and you bump into a lot of them as you travel around. Damn few of them become your traveling companions, though.”

Postscript: There will be A Memorial Celebration for Emmett Williams in New York City on Sunday, April 1 (from 7:00 p.m.) at the Emily Harvey Foundation, 537 Broadway (at Spring Street), 2nd floor. The program will include videos and live performances of Williams’ scores by artist friends and his son Garry Williams. Cake will be served. Event organizer: Geoffrey Hendricks. Contact: 212-431-8625 or cloudsmith@aol.com