Osborne is a composer, musicologist and social historian. He divides his time between New Mexico, where he was born, and Germany, where his wife Abbie Conant is a professor of trombone at the University of Tubingen.

and Racism in American Classical Music

Given the many European press reports about the Vienna Philharmonic’s sexism and racism — see articles in Der Standard and Profil magazine for two recent examples — one might ask why the orchestra continues to be euphorically received in the United States. How can we explain that the Philharmonic’s sexist and racist employment practices are largely overlooked? Does this acceptance have something to do with classical music and the nature of America’s cultural life?

One of the most obvious answers involves the demographic of American classical music, which is overwhelmingly white and elitist. Forty years after the American civil rights movement began, the country’s major orchestras are still 98% white; its conductors are still 99% white; the composers presented are almost 100% percent white; and the audience at least 95% white — even though the urban areas where these orchestras reside are from 30% to 50% black.

Many Americans rationalize this situation with the naive (and smug) assumption that African-Americans have their own rich musical traditions and are simply not interested in classical music. Such views, of course, are absurd and racist. They represent a form of aesthetic segregation. It is grotesque that one would even need to explain that the talents of African-Americans are as manifest in classical music as in jazz and pop. We practice musical racism through bourgeois essentialism that presumes to define black and white forms of taste and ability.

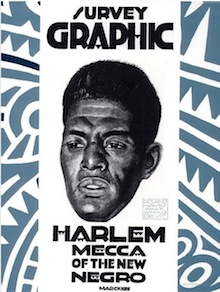

These racially informed perspectives are strengthened by our plutocratic method of funding the arts. Most of our funding comes from donations by the wealthy, which inevitably allows a racially based class system to strongly influence our cultural lives. Elite white interests, as represented by institutions such as Lincoln Center, are where the money goes, while the cultural needs and identities of the poor and colored remain mostly ignored.This is clearly illustrated if we look at the cultural status of areas such as Harlem. Due to its remarkable history, Harlem should be one of the great artistic centers of the world, a cultural Mecca visited by millions around the globe each year. The reality is almost the opposite. Instead of being the pride of New York City, for over half a century Harlem has been decimated by poverty, degradation, and neglect. The area must continually struggle to maintain its cultural existence. Our Eurocentric perspectives not only inure us to the sexist and racist values that shape institutions like the Vienna Philharmonic, they blind us to profound forms of cultural expression directly in our midst. And worse, they create forms of racist neglect and contempt that actually destroys culture.

With an irony so extreme it boggles the mind, whites have recently taken an interest in Harlem, but only as developers who want to make fortunes by gentrifying it. (These developers include Columbia University which plans to expand its campus into the area.) In an age-old pattern, as the real estate prices rise, African-American residents will be forced into yet another racist, cultural Diaspora that will weaken both their and New York City’s cultural identity. (The destruction and rebuilding of New Orleans along elite white interests is another well-known illustration.)

None of this should be surprising. An ethnocentric and self-serving perspective is an inherent part of any racially informed plutocratic system of arts funding. While most concert halls in Europe, for example, are named after great cultural figures in their history, our halls are usually named after wealthy white people whose backgrounds are so mundane we don’t even know who they really are. Even if these cultural institutions are built in areas where the poor live, they are surrounded by social barriers that allow for very little communal interaction.

An effective integration of our “minority” communities into classical music would require a commitment to education and accessibility that simply does not exist in the United States, and probably never will under its current system of funding the arts. Programs exist, of course, but they fall vastly short of what is needed. The problems represented by our extreme social dichotomies are simply not within the purview of corporate donors. And the wealthy alone could never solve such immense problems.

We also have to admit no solution is in sight. Our political culture refuses to acknowledge that our massive legacy of human slavery is a responsibility so large it can only be met and solved by our government. As a result, paradoxes abound. Why have we spent a trillion dollars to occupy and “rebuild” Iraq, for example, while leaving close to 30 million of our own citizens in ghettos where they live deeply deprived and degraded lives? Can it be any wonder a society like ours could easily overlook the racism of the Vienna Philharmonic?

The ironies of our one-sided cultural policies were vividly illustrated when New York’s cultural elite built Rose Hall, a new venue for jazz at Lincoln Center, while continuing to ignore the decades-long cultural destruction of Harlem. On one hand, it is wonderful that African-American culture can be celebrated near the most privileged center of New York’s cultural life. But, on the other hand, it cannot be overlooked that the entire orientation of the hall’s programming has been shifted toward a conformist form of jazz stripped of its traditional sense of protest, and oriented toward consumption by a white gentry capable of paying for high-priced tickets. It is little wonder that cynical observers sometimes refer to Rose Hall as the Lincoln Center Jazz Plantation — a terribly harsh metaphor, but not without an important point.We are left with the vague but prevalent idea that black and Hispanic communities are little more than something over which an elevated freeway is built so whites can rush to their comfortable suburbs. It is simply not considered that those communities have rich cultural lives that should be supported and made a central and vibrant part of America ‘s cultural experience and identity. And it is not considered that these communities should receive the same opportunities for education in classical music made available to many whites (whether those whites use it or not.)

As a result of these social practices, a bizarre atmosphere surrounds places like Lincoln Center or Carnegie Hall. In ways that have yet to be fully studied, the patrician rituals of classical music vicariously celebrate the highborn and racist character of our Eurocentric cultural heritage. In the euphoric reception of the Vienna Philharmonic, and in the large amount of funding it is given for yearly appearances, one senses a quiet, bourgeois celebration of the ensemble’s sexism and racism.

There are many issues enfolded in this cultural landscape. We already feel the devastating loss of whole cultures within our culture. Can we move beyond a mere hip comodification of world music, to a genuine racial and cultural integration in classical music itself?