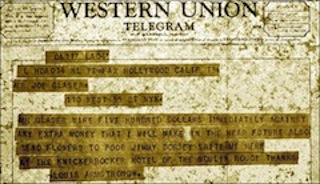

Somehow in all the reports I’ve seen about Western Union’s last telegram (sent on Jan. 27) and the end of an era, there was the usual nostalgia for a bygone technology and the usual chronicle of Samuel Morse and the invention of the telegraph, and the usual summary of famous (even apocryphal) telegrams sent by William Randolph Hearst, JFK, Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, Cary Grant and so on. But there was no mention anywhere I looked of the man who wrote the greatest homage to Western Union ever penned: Henry Miller.

Somehow in all the reports I’ve seen about Western Union’s last telegram (sent on Jan. 27) and the end of an era, there was the usual nostalgia for a bygone technology and the usual chronicle of Samuel Morse and the invention of the telegraph, and the usual summary of famous (even apocryphal) telegrams sent by William Randolph Hearst, JFK, Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, Cary Grant and so on. But there was no mention anywhere I looked of the man who wrote the greatest homage to Western Union ever penned: Henry Miller.

![HENRY MILLER [Photo: George S. Barrows]](http://www.metroactive.com/papers/sonoma/11.23.00/gifs/miller-0047.jpg) The reason, of course, is that Miller’s homage is no homage at all. It is the bitter opposite. He does not wax nostalgic, sentimental, romantic, or patriotic. His memories of Western Union, where he worked for several years in the early to mid-1920s, were engraved forever in “The Tropic of Capricorn.” Describing his experience as employment manager for New York’s messenger department, he calls Western Union the Cosmodemonic Telegraph Company (sometimes the Cosmococcic Telegraph Company) and offers an indelible, angry, funny, ranting satire of corporate bureaucracy that goes well beyond the usual.

The reason, of course, is that Miller’s homage is no homage at all. It is the bitter opposite. He does not wax nostalgic, sentimental, romantic, or patriotic. His memories of Western Union, where he worked for several years in the early to mid-1920s, were engraved forever in “The Tropic of Capricorn.” Describing his experience as employment manager for New York’s messenger department, he calls Western Union the Cosmodemonic Telegraph Company (sometimes the Cosmococcic Telegraph Company) and offers an indelible, angry, funny, ranting satire of corporate bureaucracy that goes well beyond the usual.

One day by chance, Miller writes, “when I had been put on the carpet for some wanton piece of negligence, the vice-president let drop a phrase which stuck in my crop. He had said that he would like to see some one write a sort of Horatio Alger book about the messengers; he hinted that perhaps I might be the one to do such a job. I was furious to think what a ninny he was and delighted at the same time because secretly I was itching to get the thing off my chest. I thought to myself — you poor old futzer, you, just wait until I get it off my chest … I’ll give you an Horatio Alger book … just you wait!”

I saw the Horatio Alger hero, the dream of a sick American, mounting higher and—higher, first messenger, then operator, then manager, then chief, then superintendent, then vice-president, then president, then trust magnate, then beer baron, then Lord of all the Americas, the money god, the god of gods, the clay of clay, nullity on high, zero with ninety-seven thousand decimals fore and aft. You shits, I said to myself, I will give you the picture of twelve little men, zeros without decimals, ciphers, digits, the twelve uncrushable worms who are hollowing out the base of your rotten edifice. I will give you Horatio Alger as he looks the day after the Apocalypse, when all the stink has cleared away.

Read the whole passage. It includes a stunning indictment of a brutal system that was taken up again two decades later by Allen Ginsberg, in “Howl,” which by the way bears a striking resemblance to it in literary style and passionate rhetoric.

Here’s Miller in 1938:

I saw the army of men, women and children that had passed through my hands, saw them weeping, begging, beseeching, imploring, cursing, spitting, fuming, threatening. I saw the tracks they left on the highways, the freight trains lying on the floor, the parents in rags, the coal box empty, the sink running over, the walls sweating and between the cold beads of sweat the cockroaches running like mad; I saw them hobbling along like twisted gnomes or falling backwards in the epileptic frenzy, the mouth twitching, the saliva pouring from the lips, the limbs writhing; I saw the walls giving way and the pest pouring out like a winged fluid, and the men higher up with their ironclad logic, waiting for it to blow over, waiting for everything to be patched up, waiting, waiting contentedly, smugly, with big cigars in their mouths and their feet on the desk, saying things were temporarily out of order.

Here’s Ginsberg in 1956:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked … who were burned alive in their innocent flannel suits on Madison Avenue amid blasts of leaden verse & the tanked-up clatter of the iron regiments of fashion & the nitroglycerine shrieks of the fairies of advertising & the mustard gas of sinister intelligent editors, or were run down by the drunken taxicabs of Absolute Reality, who jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge this actually happened and walked away unknown and forgotten into the ghostly daze of Chinatown soup alleyways & firetrucks, not even one free beer, who sang out of their windows in despair, fell out of the subway window, jumped in the filthy Passaic, leaped on negroes, cried all over the street, danced on broken wineglasses barefoot smashed phonograph records of nostalgic European 1930’s German jazz finished the whiskey and threw up groaning into the bloody toilet, moans in their ears and the blast of colossal steamwhistles …

They both come out of Whitman, natch. Case closed.