There’s much to be said about John Gray’s essay, “The Mirage of Empire,” in the current issue of The New York Review of Books. Gray’s comments are focused on the themes of two books under review — Robert D. Kaplan’s “Imperial Grunts” and Michael Mandelbaum’s “The Case for Goliath” — and to some extent are constrained by them. Nevertheless, we were struck by contradictions between Gray’s views and ours, largely about U.S. strategy in Iraq.

This left us dumbfounded because, as we’ve said before, Gray is our fave philosophe. More important, he possesses a scholarly authority that we’re in no position to challenge. (Gray is School Professor of European Thought at the London School of Economics and the author of “False Dawn: The Delusions of Global Capitalism,” “Liberalism (Concepts in Social Thought),” “Two Faces of Liberalism,” “Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals,” “Al Qaeda and What It Means to Be Modern” and, his latest, “Heresies.”)

This left us dumbfounded because, as we’ve said before, Gray is our fave philosophe. More important, he possesses a scholarly authority that we’re in no position to challenge. (Gray is School Professor of European Thought at the London School of Economics and the author of “False Dawn: The Delusions of Global Capitalism,” “Liberalism (Concepts in Social Thought),” “Two Faces of Liberalism,” “Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals,” “Al Qaeda and What It Means to Be Modern” and, his latest, “Heresies.”)

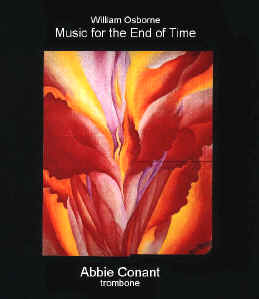

So we passed the buck to our in-house scholar, William Osborne, who summed up his response to Gray in a nutshell: “He does not seem to understand how the new world order works.” Osborne, a temperamentally shy, but not intellectually bashful, ex-patriate American composer, feminist, musicologist, cultural commentator, music critic, social critic and activist, backed up his conclusion with closely argued ideas that refute Gray point by point. Here’s the debate:

John Gray: No doubt modish theories that understand warfare as an exercise in managerial efficiency contributed to the debacle [in Iraq.] However, if America is facing strategic defeat in Iraq the reason is not that its forces there are insufficiently numerous. It is that their operations have never served any political goal that could be realized.

William Osborne: The Pentagon’s understanding of war is not “managerial efficiency” (a relic of the old industrial forms of large-scale war that are not relevant in the post-cold-war world). The principle forces now opposing global capitalism are ethnic and sectarian. These are the forces the Pentagon knows it must now exploit and where necessary destroy. The military strategy in Iraq is the creation of long-term, genocidal sectarian chaos to wear down opposition to the U.S. More specifically, the political goal is civil war resulting in genocide that will quell Sunni resistance. The U.S. understands this will take 15 years — similar to the long-term forms of destruction it spawned to subdue Latin America for the last 80 years. Our government also knows that it must disassociate itself from this potentially genocidal civil war by claiming it is no longer in control of events. In addition, the Iraqi Kurds will be given a great deal of autonomy. Turkey’s opposition to Kurdish autonomy will be quelled by allowing Turkey into the European Union. Gray underestimates the slyness and criminal brutality of the U.S.’s strategic genius.

Gray: In effect America’s military adventures are paid for with borrowed money — notably that lent by China, whose purchases of American government debt have become crucial in underpinning the U.S. economy. This dependency on China cannot easily be squared with the idea that the US is acting as the world’s unpaid global enforcer. It is America’s foreign creditors who fund this role, and if they come to perceive U.S. foreign policy as dangerously threatening or irrational they are in a position to raise its costs to the point where they become prohibitive.

Osborne: I think this understanding of global capitalism is too simple. Global economics is not based on the creditor-consumer models used by individuals or corporations. By pumping billions in interest payments into China, and by strengthening its economy with lopsided trade balances, a new industrial base and market is created that will further strengthen the power of global capitalism. (And as an added benefit, it also greatly weakens Western labor unions.) In other words, those who print money (or create it as an electronic balance) work according to entirely different economic laws and principles than normal creditors and borrowers. China alone will never be in a position to raise the cost of debt since control of the global economy is not solely in its hands. It might demand higher debt payments, but global capitalism defines the very meaning of money itself. Producing high debt almost always strengthens the power of global capitalism. It doesn’t matter whether the debt is in Brazil, America, or anywhere else as long capital expansion can be maintained.

Gray: However, it is far from clear that this exercise in geopolitics can succeed. Because of the anarchy that prevails in much of the country, multinational companies are unable to operate in Iraq. Oil production has failed to reach the levels it achieved under Saddam, and if oil facilities elsewhere in the Gulf come under persistent attack it may not be possible to ensure their security. The underlying political reality in the region is pervasive hostility to American power. As a result of its oil dependency America has committed itself to a neoimperial strategy of military intervention that can only aggravate that enmity. It is doubtful whether the U.S. has the capacity to sustain the indefinite period of war that could result, and more than doubtful that the task is worth attempting.

Osborne: The U.S. knows what it is doing. Its economic hegemony is won by long-term strategic wars of slow destruction and not quick tactical victories. It will reduce troops to a low level in Iraq and keep them out of harm’s way in the large bases it has built while the 15-year-long genocidal war it has set in motion breaks the will of the resistance. The U.S. understands very well that 15 years is a short time in terms of global strategies. (The Iran-Iraq War and the 10-year embargo were also part of this long-term strategy which taken together makes it roughly a 30-year plan.) Even if the U.S. withdraws completely, the Iraq Civil War will continue and eventually allow for American hegemony. And the “enmity” toward the U.S. that Gray speaks of is also largely irrelevant. When you can thoroughly weaken people by spawning massive destruction, it hardly matters whether you are liked or not. As Latin America illustrates, it is U.S. power that rules, not U.S. popularity.

Osborne: The U.S. knows what it is doing. Its economic hegemony is won by long-term strategic wars of slow destruction and not quick tactical victories. It will reduce troops to a low level in Iraq and keep them out of harm’s way in the large bases it has built while the 15-year-long genocidal war it has set in motion breaks the will of the resistance. The U.S. understands very well that 15 years is a short time in terms of global strategies. (The Iran-Iraq War and the 10-year embargo were also part of this long-term strategy which taken together makes it roughly a 30-year plan.) Even if the U.S. withdraws completely, the Iraq Civil War will continue and eventually allow for American hegemony. And the “enmity” toward the U.S. that Gray speaks of is also largely irrelevant. When you can thoroughly weaken people by spawning massive destruction, it hardly matters whether you are liked or not. As Latin America illustrates, it is U.S. power that rules, not U.S. popularity.

Gray: As a result of the Bush administration’s intervention in Iraq the dissolution of America’s global hegemony that is an integral part of the process of globalization has been accelerated, perhaps by a generation. The United States will continue to be pivotal, but it cannot expect its interests or its values to be accepted as paramount. We are moving into a world in which peace will depend on concerted action by several great powers. In these circumstances a revival of realist thinking is overdue. Global security is not served by launching messianic campaigns to export democracy. Nor is it advanced by pursuing a mirage of empire, which even now is melting away.

Osborne: This war was never a messianic campaign to export democracy. (Nor was replacing the freely elected Allende with the mass-murdering dictator Pinochet; nor was the mass-murdering dictatorship we created in Argentina; nor the U.S.- trained and -funded mass-murdering death squads in Central America; nor the U.S.- backed, mass-murdering regime in East Timor.)

The democratization of Iraq is a propaganda lie from the same folks who said the war was about WMD. The purpose of the invasion was to set in motion a 15-year-long genocidal civil war that will destroy Iraq and allow the U.S. to dominate what is left — the oil and strategic position of the country. As I said, this is actually the second part of a 30-year strategy that also employed the Iran-Iraq War (in which the U.S. supplied arms to both sides and which led to over a million deaths) and the 10-year embargo, which the U.N. estimates caused about half a million deaths.

But Gray is correct when he says that America will indeed become less and less relevant as global capitalism evolves. Global capitalism is a trans-national order that will ultimately suppress most forms of nationalism. We should also remember that in order to survive, global capitalism must always expand into new sources of capital — either technological or material. This expansion, both technological and material, will always require war. If long-term peace does come, global capitalism will collapse. For that reason we will never have long-term peace without the creation, acceptance, and implementation of a more advanced economic system. So far, such a system has not even been conceived.

Postscript: Speaking of cowboy art, Gray quotes Kaplan as saying, “Just as the stirring poetry and novels of Rudyard Kipling celebrated the work of British imperialism in subduing the Pushtuns and Afridis of India’s Northwest Frontier, a Kipling contemporary, the American artist Frederic Remington, in his bronze sculptures and oil paintings, would do likewise for the conquest of the Wild West.”

Gray: This reference to the Wild West is not an insignificant detail. It is central to Kaplan’s picture of American Empire. He writes: “‘Welcome to Injun Country’ was the refrain I heard from troops from Colombia to the Philippines, including Afghanistan and Iraq. … The War on Terrorism was really about taming the frontier.”

Osborne: Genocide has always been a discretely practiced part of the American ideal.

— Tireless Staff of Thousands

PPS: A blast from Doug Ireland —

Brother Jan,

I have lots of problems with some of John Gray’s thinking and writing, and not only in his piece for the New York Review of Each Other’s Books. But your man Osborne displays what I think is a widespread disease on the left of the left, i.e., sloppy use of language, in this case the word “genocide.” The word has a very precise meaning, and is, unfortunately, much over-used by anti-imperialists of a certain stripe, and inaccurately so, as in multiple instance’s in Osborne’s comments. (I feel the same way about the words “fascism” and “fascist,” “Nazi,” etc., which are also terribly overused, and imprecisely so, on the left.)

I have lots of problems with some of John Gray’s thinking and writing, and not only in his piece for the New York Review of Each Other’s Books. But your man Osborne displays what I think is a widespread disease on the left of the left, i.e., sloppy use of language, in this case the word “genocide.” The word has a very precise meaning, and is, unfortunately, much over-used by anti-imperialists of a certain stripe, and inaccurately so, as in multiple instance’s in Osborne’s comments. (I feel the same way about the words “fascism” and “fascist,” “Nazi,” etc., which are also terribly overused, and imprecisely so, on the left.)

Also, Osborne mis-speaks when he writes of a ” U.S.-backed, mass-murdering regime in East Timor.” It was the Indonesian regime in Djakarta that directed the slaughter in East Timor, not an East Timorese regime. Imprecisions of this sort drive me crazy, and weaken what ought to be a powerful, radical, anti-imperialist critique.

By the by, one point I do agree with Gray on, and that is his prediction that, eventually, the American empire will become so over-extended that it can no longer sustain its adventures. It may take a little longer than both Gray and Osborne suggest, but history teaches us that all empires eventually implode for that reason, and ours will be no different. Whether you and I will be around to see this happen to the American imperium is something I have my doubts about.

Regards as ever,

Doug

FYI: I’m not referring to Osborne in my parenthetical on “fascism,” which I didn’t notice him use in his comments on Gray — it’s just one of my pet peeves. I always refer people to the superb historian Robert Paxton’s last book, which came out in ’04, “The Anatomy of Facism.” It’s the summing up of all he’s learned in his lifetime of work on the subject, and largely supplants the earlier classic texts of Franz Mehring and Ernst Nolte on the matter. If you haven’t read it, I heartily recommend it to you. Paxton, you know, is credited with single-handedly reviving the history of French collaboration with the Nazis during the occupation — and is so credited by the froggies themselves!! As you know, it was a taboo subject in France for decades, a taboo which Paxton’s books broke, opening the way for others. That’s quite an achievement. Paxton is widely respected and honored in France nowadays for that reason.

The question of collaboration has been a preoccupation of mine ever since, as a kid of 14, I read (in English translation) Andrew Schwarz-Bart’s magnificent novel, “The Last of the Just” (“Le Dernier des Justes”), which had an influence in shaping my values system that has never left me. And I’ve done a great deal of reading on the French collaboration over the last decades, it’s a subject I know rather well, becaue it’s a case study with many lessons. What I learned from Schwarz-Bart is that the varying degrees of collaboration — passive as well as active — all still boil down to collaboration. And it’s a problem that is posed every single day — to what degree does one collaborate, actively or passively, with an evil system and evil ideologists? Or, as we used to say in the ’60s, “If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.” Or, as Goethe wrote in Young Werther, “Every step one takes costs the lives of a thousand poor little worms….”

Arts, Media & Culture News with 'tude

This blog published under a Creative Commons license

an ArtsJournal blog