National Public Radio made a huge mistake ousting its veteran

arts reporter David D’Arcy and is still trying to cover it up. The latest

attempt came during an investigation by the National Labor Relations Board when the network

refused to produce documents that would allegedly clarify why he was fired and Tom Cole, a

unionized NPR staff editor who supervised the story, was disciplined.

D’Arcy, left, who freelanced for NPR for 21 years, was fired in January

D’Arcy, left, who freelanced for NPR for 21 years, was fired in January

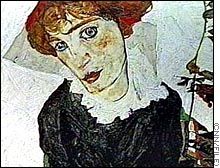

after the Museum of Modern Art complained about a story he did exposing the museum’s

involvement in a case of Holocaust art theft (the Egon Shiele painting “Portrait of Wally”) and

pointing out the contradictory stands on Nazi-looted art restitution expressed by both MoMA and

its billionaire board chairman Ronald Lauder, who also happens to collect Shiele paintings.

In addition to firing D’Arcy, NPR ran a “correction” to the story that

experts on the restitution of Nazi-looted art say is misleading and brazenly inaccurate, not to

mention damaging to D’Arcy’s reputation for thorough, in-depth reporting on the issue of

Holocaust art theft.

“NPR failed to provide documentation about mysterious activities on this matter, which they

say is confidential,” says Ken Greene, who sought the NLRB investigation as a union official of

the American Federation of Television and Radio Artist’s Baltimore-Washington chapter. “They

cited attorney-client privilege for information we requested. We say this information was not

between attorneys and clients but between managers.”

The “mysterious activities” involve “what happened during three weeks, from Jan. 6 to 27,”

he said. That is around the time MoMA is alleged to have brought pressure on NPR in phone calls

and other communications with NPR President and CEO Kevin Klose and NPR news executives.

“They never asserted attorney-client privilege about this information until the NLRB

investigation,” Greene added. “But the union expects the information to be disclosed when we

subpoena witnesses for an

The NLRB investigation was dismissed, and NPR avoided the charge of unfair labor

practices. The best prospect for sorting out the mystery, it now seems, should come at the

hearing, which has been tentatively scheduled for several alternative dates in July, Greene

says.

Another source, who asked not to be identified, confirms that NPR “didn’t want to produce

certain documents they say is privileged because of possible litigation against NPR by D’Arcy.”

It’s worth noting, however, that D’Arcy has not sued NPR, has never threatened to do so and,

according to a third source, would be reluctant to take that course of action.

These documents, sources tell me, would show that MoMA threatened

These documents, sources tell me, would show that MoMA threatened

by fax, phone, e-mail and/or letter not to cooperate with NPR reporters on future stories if it did

not repudiate D’Arcy’s piece, even though nobody at NPR — including Klose, left, who was

directly contacted by MoMA, according to a source — had ever claimed D’Arcy’s report was

factually inaccurate.

Further, D’Arcy has sworn in an affidavit for the union’s arbritration hearing that in the first

week of January, after his story aired but before MoMA began applying pressure to top NPR

executives, NPR assistant managing editor Bill Wyman praised it. “He told me, ‘This is just the

kind of journalism I want the culture desk to be doing.’ He told me that. At no time during the

preparation of the story or during the editing was any criticism raised about the way I went about

reporting it.”

The reason for firing D’Arcy, as it now stands, is not inaccurate reporting. It’s that he violated

NPR’s ethical standards for failing to report the story in a “fair and balanced” way. In a

conversation with NPR management, D’Arcy was accused of “making Ronald Lauder look like a

hypocrite … and MoMA’s trustees look like bad Jews.”

If you read the transcript of D’Arcy’s report, broadcast on Dec. 27, you’ll see it says, “At

MoMA’s opening last month, Lauder talked about guidelines for institutions and collectors.” If

you listen to the report, you hear the ambient noise of the opening. Lauder was at the opening and

took questions from the press. D’Arcy asked Lauder, one-on-one, what should happen to art

identified as objects seized by the Nazis, which had not been returned. Lauder said it should go

back to the families who had owned it.

“That was the question, that was the answer,” D’Arcy recalls. “Lauder also said he thought

MoMA was doing a better job of looking into its collection [for looted art] than other museums in

Europe had done. We talked quite a bit about collecting art from Middle Europe. I got a general

statement about MoMA policy from its chairman and sought to clarify their implementation of the

policy with MoMA’s legal counsel.”

Yet MoMA has argued in court that the Schiele painting in

Yet MoMA has argued in court that the Schiele painting in

question, “Portrait of Wally,” right, which was Aryanized from Jews who feared for their lives in

1939, is no longer legally stolen and, therefore, their heirs have no legal basis for a claim to

ownership either in the United States or in Austria. “Wally” was on loan to MoMA in 1997 from

the Leopold Foundation in Vienna when heirs of Lea Bondi Jaray — from whom “Wally” was

stolen — spotted the picture and asked the museum not to ship it out of the country so they could

eventually reclaim it. The museum insists it is bound by a loan contract to return “Wally” to the

lender.

As to the allegation in NPR’s posted “correction” that he did not allow MoMA to reply to

critical comments, D’Arcy says: “That’s ridiculous. Moma knew what it didn’t want to talk about

and declined to comment, in writing. MoMA knows this better than anyone. Its awareness of the

public relations risk in trying to explain a conflicted position in the Schiele case may account for

its refusal to talk with other reporters besides me, like Morley Safer of CBS News and Marilyn

Henry of ArtNews.”

And D’Arcy adds, “while I was preparing the story, an NPR editor sat in on at least two of

the interviews in which critics characterized MoMA’s activities. The editors knew the nature of

the criticism being directed at MoMA in this case. These criticisms had been raised for the past

seven years.”