When I was looking at my old Bob Woodward interview, some of which I posted because it seemed, uh, timely, I saw another old interview I did — this one with Bill Burroughs. I thought you’d find it interesting. Here’s part of it:

Your books are filled with gun lore. What spurred your interest in guns?

That was just the way I was brought up. In the 1920s, America was a gun culture. Everyone got a certain gun. You got your air gun and your single-shot .22 and so on. I was brought up with guns. When I was living in Europe and New York, I put that aside. And when I came back to smalltown living like this [He was living in Lawrence, Kansas], I was able to take up that hobby again, as well as the whole consideration of weaponry in the widest sense, from guns to biological mutation to religion. It’s all weapons.

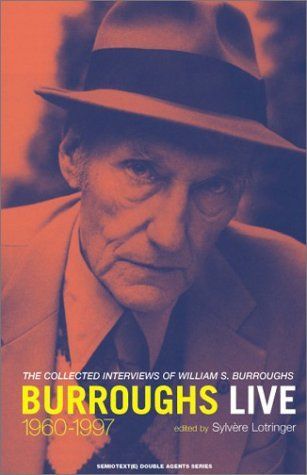

[Burroughs’ portrait with pistol, 1990, by Gottfried Helwein]

Why are you increasingly preoccupied with themes of biological mutation and space travel?

Well, I think that’s the only place the species can go. Man is an artifact for space travel in a state of arrested evolution.

Does this view have anything to do with the fact that you’ve gotten older and dying is closer?

No, my opinions on that haven’t changed in 50 years.

And they are?

Well, of course, I believe in reincarnation, which is a very bad idea at the present time. The point is that you don’t move of your own volition any more than a chair does, being very much the same substance. In other words, what animates the human body is an electromagnetic field. Now an electromagnetic field can theoretically be moved, given the knowledge, from one situation to another. It could conceivably exist without a physical body. It exists in a computer. There are many possibilities. You aren’t your body any more than a pilot is the plane, although the pilot has to observe certain rules or he’s going to be in very bad trouble. He can’t step out of his plane at 35,000 feet. There are all sorts of things he can’t do if he’s going to survive.

Since you’re writing for the space age, as you’ve said, do you have any faith in space programs?

The space programs have demontrated a very useful thing. Of course, they’ve simply sent these people up in an aqualung. It’s like taking some fish in an aquarium and bringing them up on the land. But they still have made a very useful demonstration that man can actually leave Earth. It’s one of the few public expenses that I don’t begrudge. But it’s only a first step. My feeling is that the transition from time into space is going to be quite as drastic as the transition from water to land.

Why have you called Christianity a “dangerous illusion?”

The point is that the one-god universe is a dead-end horror. All right, he’s all-powerful and all-seeing. It means that he can do everything and he can do nothing. Doing implies opposition. He can’t change because change implies introspection and action in opposition to something. In other words, this is the classic thermodynamic universe. It’s bound to run down by definition. That’s what I’m talking about. The magical universe, which is unpredictable and spontaneous, is a living universe. The one-god universe is dead. And that goes for any one-god religion. Islam is just the same.

Of all your books, which do you think is the best?

I withhold judgment. Writers are poor judges of their own work. They always tend to think that the book they’ve just written that minute is the one. In some cases it’s glaringly untrue. James Jones didn’t realize that From Here to Eternity was his only book.

What about Jack Kerouac?

Well, On the Road became such a classic and said so much to so many people in America and Europe and elsewhere that it did tend to eclipse his other work. I had the impression that in the last two or three years of his life he was hardly writing at all. Whether he knew it or not, he was dying. I don’t know if any doctor held a gun to his head and told him, “If you don’t stop drinking, you’re dead.” If that had been done, say, five years before he was dead, it might have saved him. Because you can get along with, oh, I think 10 percent of liver function. But you can’t get along with none.

You are often referred to as a “scion of the Burroughs adding machine fortune.” How did that fortune break down?

Oh, it’s pretty simple. My grandfather, the inventor, died at the age of 41 in Alabama of tuberculosis. That would be about 1897. My father, I think, was 12 years old. So the children were quite young. There were four children — Aunt Jennie, Aunt Helen, and Horace, and my father Mortimer. What apparently happened was that the board of directors persuaded them that the whole idea [of the adding machine] was impractical and they’d be better off to take any offer they can get. Obviously, it looks from here like a plot on the part of the executors and investors to buy the family out. The children received $100,000 each. That $400,000 in stock would now be worth about $50 million. My father started a glass company with his $100,000 and he ran that quite successfully for a number of years.

When you first met Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac in the 1940s, were you living off a trust fund?

No. All that stuff about a trust fund is absolutely rubbish. That was all concocted by Jack Kerouac.

The complete interview ran in the Chicago Sun-Times in 1984. My first contact with Burroughs, who died in 1997, came during the late ’60s in a brief correspondence about publishing some of his writing in a small San Francisco literary magazine. I first met “Uncle Bill” — as Carl Weissner and I used to refer to him — in London, where I visited him in his flat in 1971. Uncle Bill, in a Rolling Stone interview reprinted in Burroughs Live, recalled a video experiment we made during that visit. The tape still exists, but I haven’t watched it in more than 30 years. I hope it still holds the scary images we produced by projecting other faces on Burroughs’s and recording them in sync with his voice and lips. The result, if I remember correctly, looked like a mummy coming to life. Uncle Bill subsequently wrote a “tickertape” that served as a running commentary for a book of experimental fiction Weissner, Jurgen Ploog and I co-wrote, called Cut Up or Shut Up. It was published in Paris in 1972 by Jochen Gerz’s Editions AGENTZIA.

The complete interview ran in the Chicago Sun-Times in 1984. My first contact with Burroughs, who died in 1997, came during the late ’60s in a brief correspondence about publishing some of his writing in a small San Francisco literary magazine. I first met “Uncle Bill” — as Carl Weissner and I used to refer to him — in London, where I visited him in his flat in 1971. Uncle Bill, in a Rolling Stone interview reprinted in Burroughs Live, recalled a video experiment we made during that visit. The tape still exists, but I haven’t watched it in more than 30 years. I hope it still holds the scary images we produced by projecting other faces on Burroughs’s and recording them in sync with his voice and lips. The result, if I remember correctly, looked like a mummy coming to life. Uncle Bill subsequently wrote a “tickertape” that served as a running commentary for a book of experimental fiction Weissner, Jurgen Ploog and I co-wrote, called Cut Up or Shut Up. It was published in Paris in 1972 by Jochen Gerz’s Editions AGENTZIA.