A tour of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, the official name of the Berlin Holocaust memorial designed by Peter Eisenman, draws a powerful review from architecture critic Nicolai Ourousoff, whose reviews have usually left me cold. But not this time.

“The memorial’s power lies in its willingness to grapple with the moral ambiguities arising in the Holocaust’s shadow,” Ourousoff writes in today’s New York Times. “Its focus is on the delicate, almost imperceptible line that separates good and evil, life and death, guilt and innocence.”

Echoing Eisenman’s own statements about the thin membrane between the mundane and the cosmic, he writes:

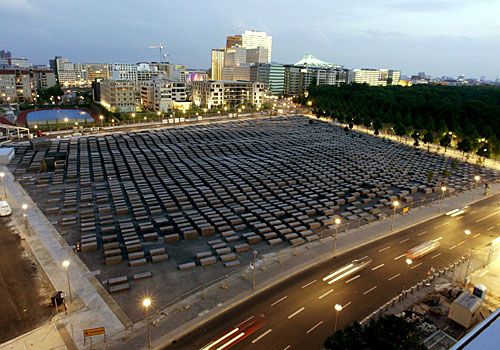

In other words, you have to be there to sense the true impact of the place. Even so, the photos accompanying this item are worth seeing. From top to bottom: an aerial view showing the memorial bordered by a street and a park within the city (Jockel Finck/AP); a view of the tallest pillars — all told, the pillars vary in height from mere inches to 15 feet or so — and a cobblestone lane deep within the memorial (Harf Zimmermann for NYT); a view toward the Reichstag dome from within the memorial (Herbert Knosowski/AP); a large wall display showing Holocaust victims in the documents center located below the memorial (Michael Kappeler/AFP/DDP).[T]he memorial’s central theme is the process that allows human beings to accept such evil as part of the normal world — the incremental decisions that collectively lead to

the most murderous acts.There is no way to glean this from photographs; it can be understood only by experiencing the memorial as a physical space. No clear line, for example, divides the site from the city around it. The pillars along its periphery are roughly the height of park benches. A few scattered linden trees sprout between the pillars along the memorial’s western edge; at other points, outlines of pillars are etched onto the sidewalk, so that pedestrians can actually step on them as they walk by.

The sense of ambiguity — the concerns of everyday life, a world of unspeakable evil — will only be amplified once the memorial opens to the public [on Tuesday]. It is not hard to imagine Berliners sitting on the pillars at the memorial’s edges, reading books or sunning themselves on a spring afternoon. The day I visited the site, a 2-year-old boy was playing atop the pillars — trying to climb from one to the next as his mother calmly gripped his hand.

These moments speak to one of the Holocaust’s most tragic lessons, the ability of human beings to numb themselves to all sorts of suffering — a feeling that only intensifies as you descend into the site. Paved in uneven cobblestones, the ground between the pillars slopes down as you move deeper in.

At first, you retain glimpses of the city. The rows of pillars frame a distant view of the Reichstag’s skeletal glass dome [at right]. To the west, you can glimpse the canopy of trees in the Tiergarten. Then as you descend further, the views begin to disappear. The sound of gravel crunching under your feet gets more perceptible; the gray pillars, their towering forms tilting unsteadily, become more menacing and oppressive. The effect is intentionally disorienting. You are left alone with memories of life outside — the cheerful child, for example, balanced on the concrete platform.

It sounds from Ourousoff’s report that Eisenman’s design for memorializing the murdered Jews of Europe easily rises to, and perhaps above, the standard set by Maya Lin for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington. Which is as it should be. One day we’ll see what comes of the design for the 9/11 memorial to those who died at Ground Zero in New York, in a field in Pennsylvania and at the Pentagon in Washington. — Jan Herman