cultural boons. It is no more than a content aggregator, but its links provide some of the most

intellectual articles for a general audience to read about literature, philosophy, history, sociology

and science. I don’t mind that the site leans strongly to the libertarian right. It gives me something

to chew on. But I cherish even more the dissent it arouses, especially in my leftist friend Bill

Osborne. He doesn’t like ALD — at all.

“If it were a political blog,” he writes, “more power to them. But it is actually a listing of arts

and letters that is owned by the Chronicle of Higher Education. College students should not read

just one side of the story, not left or right. That’s just bad journalism, and bad education. “On the

other hand,” he added, “maybe that’s what education is. In the past it has been a culture war

against stupid bigotry. In that sense, my college education very much helped me. Now the bigots

are firing back. Underneath is a hidden ethos that reads, Long live the old South etc., even

if they try to hide it with tokenism.”

When I joked that perhaps ALD was turning over a new leaf, having just listed an article by Ramsey

Clark, the former U.S. attorney general under Lyndon Johnson

— it gives his reasons for wanting to be part of Saddam Hussein’s legal defense team — Bill

replied, “It doesn’t surprise me that they linked to that article. The site occasionally includes

articles from the left if it feels they will be seen as ludicrous. Scragly old Ramsey Clark

eccentrically defending Sadam makes a perfect foil. As I said, it is disappointing that the Chronicle

of Higher Education hosts that site. Yes, ALD includes some good stuff if it isn’t on the left, but

to put together such an overtly biased assemblage in the name of the Chonicle damages the

Chronicle’s reputation.”

In any case, Bill’s irritation was on full display the other day in response to Theodore

In any case, Bill’s irritation was on full display the other day in response to Theodore

Dalrymple, “The Specters Haunting

Dresden,” which had been linked from the neocon magazine

City Journal. ALD had alerted me to the article. After reading it, I asked Bill to have a look at it

because he has lived in Germany for more than a quarter centruy and has made a deep study of

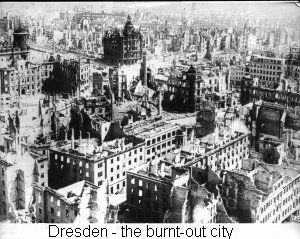

German culture. The relevance of Dalrymple’s subject to post-9/11 America is not stated

explicitly, and an upfront reference to the current bombing of Falluja would perhaps be

overdrawn. Yet some parallels are implicit. (Burnt-out Dresden, above. Bombed-out Falluja,

below.)

Dalrymple writes: “Nowhere in the world (except, perhaps, in Israel or Russia) does history

weigh as heavily, as palpably, upon ordinary people as in Germany.” But in a statement that made

me flinch, he also notes that “the shame of German history is greater than any cultural

achievement, not because that achievement fails to balance the shame, but because it is more

recent than any achievement, and furthermore was committed by a generation either still living or

still existent well within living memory.”

I

I

flinched because Dalrymple implies that, in fact, the achievement could somehow balance

the shame. Bill’s reply was pointed: “Yeah, what balances genocide? If you’re cultured enough, it

is sort of OK. What a logic!” But here’s his message in full:

“I started by glancing at the City Journal site as a whole, so I would know where the author

might be coming from. I found this in another author’s article about pomo history –or something

along those lines”:

It is still suicidal to meet the United States in a conventional war at least for

any enemy that has not fully adopted Western arms, discipline, logistics, and military organization.

The recent abrupt collapse of both the Taliban and Saddam Husseins regime amply proves the

folly of fighting America in direct conflicts. The military dynamism that enables the United States

to intervene militarily in the Middle East in a manner in which even the richest Middle Eastern

countries could not intervene in North America is not an accident of geography or a reflection of

genes, but a result of culture. Our classical Western approaches to politics, religion, and

economics including consensual government, free markets, secularism, a strong middle class, and

individual freedom eventually translate on the battlefield into better-equipped, motivated,

disciplined, and supported soldiers.

“We are going to get our asses seriously kicked in Iraq. When will these idiots figure out that

Sadam’s army dissovled by plan and that the weapons and funding caches were also all carefully

laid out. After the lessons of the first Gulf War the Iraqis knew they had to avoid a tactical war

and fight a strategic one. And when will that honky figure out that steam-rollering over

impoverished Third World countries is not a test of military might. Dick-brained hubris.

“Now that we know we cannot successfully occupy Iraq, we are going to follow the second

standard operation procedure of U.S military/economic strategy. We will so thoroughly destroy

the country that it will remain incapacitated for at least a hundred years.

“But on to the article by Dalrymple you mentioned. Yeah, what balances genocide? If you’re

cultured enough, it is sort of OK. What a logic!”

Nowhere in the world (except, perhaps, in Israel or Russia) does history

weigh as heavily, as palpably, upon ordinary people as in Germany.

“Maybe that honky should spend the next two years living on [Manhattan’s] 130th street. The

legacy of human slavery and all that has followed it has all but destroyed every major American

city. But then, he is right, from his perspective. History vanishes in the suburbs. Honkies have no

history. On the other hand, talk to blacks, or Hispanics and Native Americans of the Southwest.

They have some issues called history. Dalrymple is suffering from what might be thought of as

honky myopia. No wonder neocons talk about the end of history.

“It astounds me how even the basic infrastructure of our cities is decaying or even

non-existent. Think of how the New York subways are so out of date and also allowed to rot to

hell. The repairs on the A train will take three to five years because the old switches that have to

be replaced are of 1930s vintage and have to now be hand made.”

The estimate of the time needed for repairs has declined since our exchange, from years to months to weeks. But

Bill’s point still holds.

“I study ghetto subway stalagtites as a hobby,” he continued. “Eventually the ugly oozing

leaks that cause them will cause the walls to collapse. The honky goes on to tell about how after

the Nazis communism also destroyed German cities. In reality, there never was destruction and

squalor in the East Block that even remotely approaches the American ghettos. When whites

make that remarkable transformation to being honkies they always end up seeing only one side of

the tortilla.”

Sixty years after the end of the Second World War, the disaster of Nazism is

still unmistakably and inescapably inscribed upon almost every town and cityscape, in whichever

direction you look. The urban environment of Germany, whose towns and cities were once among

the most beautiful in the world …

“But this is a good point and one many Americans don’t fully understand, though it takes

about one day to notice it if you go to Germany.”

Well-stocked shops do not supply meaning or purpose. Beauty, at least in its

man-made form, has left the land [Germany] for good; and such remnants of past glories as

remain serve only as a constant, nagging reminder of what has been lost, destroyed, utterly and

irretrievably smashed up.

“Up here in Ghettoville, people say, my kingdom for a decent shop. And let’s not talk about

all the once beautiful, upscale parts of our cities that are now rat-infested, human dumping

grounds. My God, the honky has forgotten that Philadelphia has 14,000 buildings in a dangerous

state of collapse. But anyway, lets go get American meaning, beauty and purpose from the local

Wal-Mart, which in many towns these days is all that’s left. Honkies get so astute in their cultural

observations once they are abroad and looking at another country.”

We started it [the war], she said. We got what we deserved [the

bombing.]

“Well, I think Dalrymple doesn’t understand that Germans have official pat responses when

talking to naive Americans. There is a very considerable movement in Germany to define the

carpet bombing of the cities as a war crime. It has even been the subject of several nationally

broadcast German TV programs. They admit their own guilt, but feel that doesn’t mean that the

other side might have made bad decisions. (I’m torn two ways on this subject, but leaning toward

the war-crime side. Hiroshima tilts the scales.)

The moral impossibility of patriotism worries Germans of conservative instinct

or temperament.

“Yes, that is very true and especially affects young people. But I feel this guy hasn’t lived in

Europe very long, if at all. All Europeans share the same concerns, if not the negative attitude,

toward nationalism. Nationalism cost them about 80 million lives in the 20th century alone, and

the almost complete destruction of many of its cities far beyond Germany. All the honky

flag-waving in America would be seen in Europe as completely uncouth, almost to the point of

being bonko. But I like his attempt to explain German Anglophilia. He’s on to something there.

“Well, I am going to read on and not comment anymore if I can help it. Maybe you can see

why I don’t belong in the U.S. Something happened to my honkiness. [Bill was born and raised in

rural New Mexico in a family that lived near or below the poverty line.] And of course, you know

how I feel about Germany. I am utterly dislocated on this whole goddamn planet. I might be able

to make a go of it in Italy, but that is iffy too.”

The impossibility of patriotism does not extinguish the need to belong,

however. No man is, or can be, an island; everyone, no matter how egotistical, needs to belong to

a collectivity larger than himself. A young German once said to me, I don’t feel German, I feel

European. This sounded false to my ears: it had the same effect upon me as the squeal of chalk on

a blackboard, and sent a shiver down my spine. One might as well say, I dont feel human, I feel

mammalian. We do not, and cannot, feel all that we are: so that while we who live in Europe are

European, we dont feel European.

“Oh geez, I can’t stop with such choking remarks as this. This guy has a terminal case of red,

white and blue honkitis. No nationalism and flags to wave and he hears chalk scraping and loses

his humanity. What a fucking asshole. He ought to feel mammalian. He’s a chimp.”

In any case, can a German feel European unilaterally, without the Portuguese

(for example) similarly and reciprocally feeling European rather than Portuguese? From my

observations of the French, they still feel French, indeed quite strongly so.

“The man is an imbecile. Germans are so German they reek of it. They just have the discretion

not to strut it. When they do, people like the French, Dutch, Poles and Russians turn white and

reach for the guns. After all, one in five Poles died in World War II (6 million). And 18 million

people died in the Soviet Union. By comparison, less than 300,000 Americans died fighting both

Japan and Germany. That’s about a 60th the number in the Soviet Union.

“But of course, we claim that we defeated the Germans. The history of the war shows the

Red Army did about 80 percent of the work. Such idiotic misperceptions of history as America’s

have a lot to do with the different perspectives about nationalism and this country’s deep infection

of honkiness.”

A common European identity therefore has to be forged deliberately and

artificially …

“Uh, you mean like almost all nationalism? Gee, you’re brilliant. OK kids, let’s all stand and

say the pledge of allegiance and then go home and watch John Wayne and Sylvester Stallone

shoot Indians and gooks. Is/was Stallone just a natural cultural phenomenon and not an artificial

nationalistic construct??”

Eighteen years after the end of the war, in 1963, the pro-Nazi historian David

Irving published his first book, “The Destruction of Dresden.” In those days, he was either less

pro-Nazi than he later became or more circumspect — the memory of the war still being fresh —

but it was probably not entirely a coincidence that he devoted his first attention to an event that

Churchill suspected might be a blot on the British escutcheon. …

There were faint signs of Irving’s later acceptance of the Nazi worldview in this book, though

they probably went unnoticed at the time. Describing the state of medical services in Dresden after

the bombing, he mentioned that “a vast euthanasia-hospital for mentally incurables” was

transformed into a hospital for the wounded, without any remark upon the very concept of a

“euthanasia-hospital for mentally incurables” … Irving’s book was influential, however, precisely

because he hid, or had not yet fully developed, his Nazi sympathies.

It achieved its greatest influence through “Slaughterhouse Five,” Kurt Vonnegut’s famous

countercultural antiwar novel, published six years later, which makes grateful acknowledgment of

Irving’s book, whose inflated estimate of the death toll of the bombing it unquestioningly accepts.

Vonnegut, an American soldier who was a prisoner of war in Dresden at the time of the bombing,

having been captured during the land offensive in the west, writes of the war and the bombing

itself as if it took place in no context, as if it were just an arbitrary and absurd quarrel between

rivals, between Tweedledum and Tweedledee, with no internal content or moral meaning — a

quarrel that nevertheless resulted in one of the rivals cruelly and thoughtlessly destroying a

beautiful city of the other.

But Vonnegut, to whom it did not occur that his subject matter was uniquely unsuited to

facetious, adolescent literary experimentation, was writing an antiwar tract in the form of a

postmodern novel, not a historical reexamination of the bombing of Dresden or of Germany as a

whole. The problem that has bedeviled any such re-examination is fear that sympathy for the

victims, or regret that so much of aesthetic and cultural value was destroyed, might be taken as

sympathy for Nazism itself. The difficulty of disentangling individual from collective responsibility

for the evils perpetrated by the Nazi regime is unresolved even now, and perhaps is inherently

unresolvable.

“Dalrymple’s summations of Vonnegut might be one-sided and full of stupid

“Dalrymple’s summations of Vonnegut might be one-sided and full of stupid

innuendo. I read “Slaughter House Five” when I was young and might see it very differently now,

but I think people would be hard pressed to say that Vonnegut isn’t a writer who thinks about

things fairly deeply. His cynicism is pretty dangerous stuff — almost worse than Beckett’s

— because he mixes it with such odd humor and poor taste. But so is my disgust at “honky”

myopia. I should politlely say White America.

“Well, I skimmed on over the rest of the article. It is not information about Germany for me,

but information about how intelligent but naive Americans try to understand it. I’ve been there and

done that myself. [Vonnegut] saw Dresden the day after the bombing. He was part of a body

brigade. (Piles of dead bodies in the streets of burnt-out Dresdon, above.) Charred

corpses of children by the hundreds affect you, whether your conclusions are right or wrong.

Maybe I need to write about Americans who write about Germany.”

Seems to me you’ve just done that, Bill.

In fairness, it should be noted that, according to Policy magazine, Dalrymple “is a psychiatric

doctor working in an inner city area in Britain where he is attached to a large hospital and a

prison. His columns report on the lifestyles and ways of thinking of Britain’s growing underclass,

and in his [2002] book ‘Life at

the Bottom,’ he warns that this underclass culture is spreading

through the whole society.” To clarify further, Publisher’s Weekly says the book is essentially a

conservative “critique of liberalism and the welfare state.”