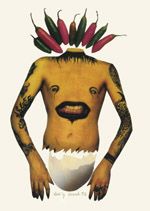

The invitation said, “They’re Old, they’re Cool, they’re Wise, and they all lived on the Lower East Side.” Needless to say, it was not an invitation to Georgie Boy’s inauguration. It was an invitation to a group show, and “they” are octegenarians — Mary Beach, whose 1998 collage “Pepper Head” (right) illustrates the invitation, Taylor Mead, Boris Lurie and Herbert Huncke, who died in 1996 at age 81. But more than age, they have in common the status of artist outsiders.

The invitation said, “They’re Old, they’re Cool, they’re Wise, and they all lived on the Lower East Side.” Needless to say, it was not an invitation to Georgie Boy’s inauguration. It was an invitation to a group show, and “they” are octegenarians — Mary Beach, whose 1998 collage “Pepper Head” (right) illustrates the invitation, Taylor Mead, Boris Lurie and Herbert Huncke, who died in 1996 at age 81. But more than age, they have in common the status of artist outsiders.

The Clayton Gallery & Outlaw Museum previews the show tonight with a reception for the artists from 6 to 8 p.m. The show opens Friday in Manhattan on the Lower East Side and runs through Feb. 27 (161 Essex St. between Stanton and Houston,

212-477-1363).

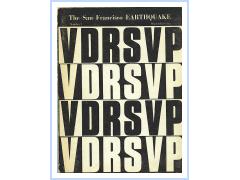

Once upon a time Mary Beach and I collaborated on a San Francisco literary magazine (left), together with Claude Pelieu, Carl Weissner and Norman Mustill. (See this item from last July.) Her life and work, like Mead’s, Lurie’s and Huncke’s, cover a lot of ground — mostly the alternative underground. From the 1930s on, the gallery notes, their combined experience includes “everything from the distant art world of prewar Europe to the literary Beat scene of New York; from Nazi prison and concentratrion camps to the Surrealist, Pop and No! Art movements; from the first Holocaust art to the streets, galleries and museums of Paris, Berlin, New York, London and San Francisco.”

Once upon a time Mary Beach and I collaborated on a San Francisco literary magazine (left), together with Claude Pelieu, Carl Weissner and Norman Mustill. (See this item from last July.) Her life and work, like Mead’s, Lurie’s and Huncke’s, cover a lot of ground — mostly the alternative underground. From the 1930s on, the gallery notes, their combined experience includes “everything from the distant art world of prewar Europe to the literary Beat scene of New York; from Nazi prison and concentratrion camps to the Surrealist, Pop and No! Art movements; from the first Holocaust art to the streets, galleries and museums of Paris, Berlin, New York, London and San Francisco.”

Of the four, Herbert Huncke and

SHIT NO! TEN YEARS AFTER

The art world is in deep crisis and has been for some time. Artificial cultivation of decorative “esthetic” values, reckless investment speculation aided by large numbers of collaborating artists have brought about a situation very much like the last stage of a bull market on the stock exchange. Esthetically and philosophically the bottom has already dropped out. The mini-movements cultivating minor esthetic modes by-passed by the pioneers of modern art are being groomed, refined, enlarged and overstated all out of proportion to their real value. Even amputated splinters of the old rebellious Dada have been converted into saleable parlor games. …

The “theoretical” part of the art market is supported by museum curators eager to please trustees and to promote large attendance by the uneducated public. It is indebted to artist-producers who operate manufacting enterprises out of mammoth lofts in New York. But the sanctity and reliability of art critics and art publications, whose full page, awe-inspiring ads and color covers have lost their magic, convince the public no longer. The museums are finally accepted for what they really are: corporate entities & private organizations controlled by a small number of not-distinguished trustees whose conflicting interests in the art market should be opened to question.

Such Sanctum Sanctorums have only been picketed; a general clean-up must begin in earnest. And many artists do understand now that their field is not just the production of art. In the most extreme cases, political confrontation has become an art form. Some are in flight from marketable objects in what is viewed as an exaggerated reaction to their unhappy findings. To many,unfortunately, all art has become useless and corrupt.

The hope is that some place, some day, a truly unmanipulated art will appear, that younger artists will become free of the art world hang-ups of their older brothers and sisters of the Fifties and Sixties, and of the poisonous atmosphere of establishment-fostered art. Let’s hope they will know better how to handle the success-monster, the ego-monster, the competition-monster, and the monster of in-group camp. These nasy monsters have always had a habit of reappearing.

The first rebellion always begins out of desperation, triggered perhaps by the realization that isolation and inwardness must be broken. The artist who understands this is free only in rebellion.

Lurie went on to describe the history of his and other downtown artists’s shows, such as “Adieu Amerique” (1959), his farewell “statement of rejection” when he was about to leave the country for good, he thought; group shows such as, “Les Lions,” at the time of the Algerian war in a cooperative basement gallery on the Lower East Side, the “Vulgar Show,” the “Involvement Show,” the “Doom Show” in 1962, which he described as “a direct attack on the danger of atomic war at the time of the Kennedy-Kruschev confrontation over Cuba, when basement air raid shelters were introduced for unprotected homes and hysteria swept the country.”

Mary Beach and Taylor Mead will be at the gallery reception tonight. Lurie, unfortunately, will not. He’s recovering from successful heart by-pass surgery, says Clayton Patterson, who

curated the group show with Anne Loretto and James Rasin.

Postscript: The opening of the show was jammed. Gallery owner, co-curator (and, I might add, a warm and generous host) Clayton Patterson sent along some photos of the guests. There’s Boris Lurie, left, sitting on his bed at home, with Clayton behind him.

Postscript: The opening of the show was jammed. Gallery owner, co-curator (and, I might add, a warm and generous host) Clayton Patterson sent along some photos of the guests. There’s Boris Lurie, left, sitting on his bed at home, with Clayton behind him.

There’s Mary Beach, right, with the writer Victor Bockris at the gallery. Taylor Mead was having a ball prancing and dancing for guests who came loaded with cameras.

There’s Mary Beach, right, with the writer Victor Bockris at the gallery. Taylor Mead was having a ball prancing and dancing for guests who came loaded with cameras.

Before the opening Mead and a friend were singing songs and strumming banjos at a party in The Pink Pony, a friendly neighborhood restaurant around the corner from the gallery. Come to think of it, Mead might have been playing a ukelele. There he is (left) at the gallery with the artist Andre Serrano (far left). Behind them are some of Mead’s acrylics canvas.

Before the opening Mead and a friend were singing songs and strumming banjos at a party in The Pink Pony, a friendly neighborhood restaurant around the corner from the gallery. Come to think of it, Mead might have been playing a ukelele. There he is (left) at the gallery with the artist Andre Serrano (far left). Behind them are some of Mead’s acrylics canvas.