I was a late convert to the e-reader. Yet once I got going, its 24/7 ready-access to the world of literature at the click of a button made me an easy candidate for seduction.

Lately, however, I have been getting lost in the Amazon Kindle Store, the victim of too many choices shelved on a flat virtual table with no personal “you’re going to love this one!” identification system yet worked out for myself. (I have never been a kindred spirit of the NYTimes bestseller list readers, and my interests are often too flaky to benefit much from those “if you like” suggestions.) Sure, I have a Goodreads account and also download samples of interesting books when those handy lists of recommended reading come along on my favorite websites, but somehow it’s not quite the same as wandering along book shelves and checking out what your local store employees are excited about this month. Maybe, you know, even having a conversation with a fellow shopper.

This came to a head recently for two reasons. On Saturday afternoon, I was cooking and listening to The Signal on WYPR. Towards the end of the program, Benn Ray of Atomic Books (the awesome book shop just down the road from me) was on as a guest to suggest some summer reading picks, including Donald Ray Pollock’s new novel The Devil All the Time (out today!). His interest in this writer was aurally evident and for me, a child of Ohio and a fan of the television show Justified, it seemed like a can’t-fail selection. Later, as I reclined on my sofa inhaling Pollock’s book of short stories in preparation while enjoying my home air conditioning, I felt bad that I hadn’t braved the heat and walked down the block to support my local bookstore (though they would have probably looked at me like a crazy person if I had handed over my Kindle and said “fill ‘er up!”). Still, I miss this simple community sharing and began to wonder if there was any practical way a bookstore of the future could provide all of the services of a bookstore–the highlights, the readings, the experience behind the product, if you will–minus the physical book, and still make enough money to survive. And if not now, would something like this find its “audience” at some point in the future?

Then, in a more abstract way, the need for the “real, live person with experience” also resonated when a colleague passed me this article yesterday morning covering the value (and values) of the developing digital media marketplace. The line that caught him was that “the food industry doesn’t have to compete with people getting food for free, nor does the gasoline industry. But with digital media, you’ve got people there who have the option of whether they’ll even pay.” Of course, you can get your food for more or less free as well, but foraging and dumpster diving is a lot more distasteful to most people than web searching, and gardening a lot more time consuming. However, like the changes we have seen when it comes to food choices for those with the resources to access them, perhaps a similar search will lead to a resurgence in valuing high quality over cheap, anonymous quantity. When it comes to music, I can almost see this road running parallel to the food trends and taking us back to a place where live music in the home once again becomes a prized skill and a sought-after experience.

Think I’m drawing false comparisons or is there a “there” somewhere in all of this?

Brave new worlds, indeed. In Orwell’s 1984, common people were forbidden to own paper, and something like the video screens of Big Brother were everywhere. The main character, Winston Smith reveled in holding paper in his hands, and dreamed of the days when paper was common. He also dreamed of the deeply satisfying rebellion that writing on paper might bring.

Marshall McLuhan famously said that digital media would make us tribal again. He described the digital world as a “total interdependence, and superimposed co-existence.†One of the characteristics of tribal societies is a very weak sense of personal property. Most everything belongs to the collective, sort of like in a large family. Europeans arriving in the new world couldn’t understand this and called Native Americans “Indian givers.†People forget that the concept of ownership is a philosophy that has evolved throughout history and has always been in a state of flux. Technology and concepts of ownership have always evolved hand-in-hand. Think of the changes in the way knowledge could be owned as the world moved from the age of manuscripts to the age of the printing press to the age of digital media.

For McLuhan, print culture created the very opposite of tribalness. Print is the technology of individualism. It is the medium of “The Author.†Knowledge in print was also reserved for the elite who had access to it. As you note, print is small, rare, and valuable. In the digital age, by contrast, the world has become a computer, an electronic brain, and we are all encyclopedic renaissance men and women with vast knowledge at our finger tips. Even the rarer, high value knowledge of which you speak can be obtained by all.

Words on paper might have a very limited “there.†They do not travel easily, and are housed in physical libraries and bookstores. Book burnings are thus hard work and never complete. In the digital world, by contrast, our thought can be located and disappeared in an instant. With a push of a button those in power can commit a kind of digital, intellectual assassination – like with the destruction of various wiki leaks sites. And as with Julian Assange, they can stop the digital flow of money, which is a big problem since paper money is going the way of paper books.

McLuhan also presciently said that terror would be the normal state in the digital world because it is so interconnected that everything affects everything. We see that the USA is the most digital and info-saturated of countries and creates more terror than any other. Another reason to long for the bygone age of print and the communities of individuals it created. The music industry and most composers still have concepts of ownership trapped in the bygone age of print.

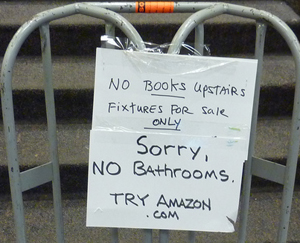

Oh, guess that “everything but the books” idea is not that original.

Post: Borders “anything but books” revitalization plan hasn’t panned out