We’ve just wrapped our first Massively Open Online Course (MOOC) Leading Innovation in Arts and Culture. This unique course was created by Dave Owens at Vanderbilt University and customized for the arts and culture sector by National Arts Strategies. This eight-week course, offered on the Coursera platform, brought more than 9,000 artists, arts administrators and cultural entrepreneurs from around the world together to discuss the specific constraints to creating good ideas in our field and to build strategies for successful innovation. This was by far the largest course on innovation in arts and culture ever implemented. This week, we are sharing some of the inspiring conversations had by our participants in the Leading Innovation in Arts and Culture course on Coursera. We encourage you to engage and add your voice to the conversation.

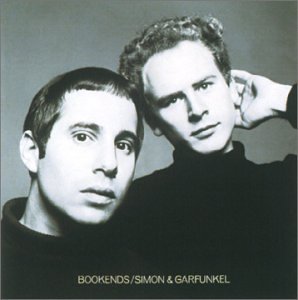

During the third week of the course, the class took a look at the role of group dynamics in innovation. We all know that it takes a village to raise a child (or a team to move an idea forward) and we work in cooperation and collaboration with others on a daily basis. In the arts and culture field this means not just colleagues inside our organizations, but partners, funders and cross-sector organizations, among others. The New York Times article, “The End of Genius” was a required reading for the class during this week and elicited an intriguing conversation surrounding genius pairs and how two brains are better than one…or not.

When it comes to collaboration, sometimes one partner can seem to be highlighted or praised more than the other for a “genius” idea. Does this come down to personality or reputation? In the case of the organization, is this reliant on who has more resources? Is it all just luck? Does it matter?

Valentina Agostini shares her thoughts:

“My idea is that most of the time the pairs complete each other. As the article says, in a pair each person needs to work and generate ideas. As we know, people can be really different: in a pair they improve their best skills to make a better work for both of them. For example one of them can be more shy in front of a public than the other one. Or he/she prefers to stay behind the scene.”

Participant Kasey Keeley highlights the role that personality can play and notes that it is not only about charisma:

“I think the personality is a large factor, but that it is quite complicated, since in different fields, different personalities (including the desire to avoid the limelight) might inspire admiration or catch people’s attention. There are plenty of artists who are admired in part because of their desire for privacy (think of Thoreau, or Dickinson), just as there are plenty of charismatics whose fame comes as much from their presence as the greatness of their ideas. I imagine luck plays some part, too – sometimes simply being in the right place to be noticed by some influential person on the right day can make all the difference (although it is possible to some extent to strategize to have this kind of thing happen, other times it really is serendipitous).”

Valerie Amor agrees:

“So if personality might be one factor could another just be luck? Some say we make our own luck – that there is a science to it. How does this fit into this discussion?”

Camilo Polo echoes the “cult of personality” but recognizes other aspects that can also come into effect:

“Although it opens up a whole new discussion on why there usually is a more favored person than the other when it comes to creative pairs, it also made me think on why sometimes pairs don’t seem to be pursuing the same actual interests in a project; I agree somehow with some of the opinions above, like the trend of cult to personality favoring one more than the other because of fitting society expectations, however this is not always the case. Sometimes a creative pair is born because they seem to agree in many project expectations, and the work they do together has great reception among their audience or clients, but when things start growing and changing, they realize the motivations have changed in one or both of them.”

Inês Beatriz Rebanda Coelho continues this conversation with the role that society plays:

“It’s a really good question and really intriguing. In my opinion it has not to do with one artist being more talented than the other or having some secret quality that the other wasn’t aware or that he couldn’t have but it’s a social thing. Society embraces the one that is more familiar to them and the one they are more comfortable with. Some authors are rejected because the society is not prepared for the novelty and innovation that they bring to the world of arts. It always passes some time for society to get used to it, until they start to understand the author and like it and it is always society who chooses who is going to be recognized next. Probably it was luck but probably it was connections. Some authors have better connections and contact with important people in the field and sometimes that are the kind of people who have power to influence the choice of the society. You always have people in your life that tell you and teach you what is really good and just good and what is not (in all the fields: art, science, culture, ethics, morals, etc.), and that influences what you like and what you dislike.”

One of the course instructors and Senior Advisor for National Arts Strategies, Jim Rosenberg places this conversation directly into the structure of some arts and culture organizations:

“This conversation made me think about the way the “genius pairs” model is built into the leadership structure at many arts and culture organizations. An artistic, creative, or curatorial leader and a strategic, administrative leader are partnered to take advantage of the unique strengths of each. Thinking about this professional pairing in our field, does it raise any more thoughts about why one member or the other in a creative pair may draw more attention? Do they draw attention in different circles? Have different interests in attention?

This split leadership model is an approach we see in lots of creative industries (fashion, gaming, advertising…). You also see this type of pairing of different skills in other industries, for example technology companies (the CEO and Chief Technology Officer) and in the most central leadership roles in larger companies (the CEO and Chief Financial Officer). If you are interested in what these pairings look like in other industries, here is a piece from Deloitte on the CEO-CFO pairing. And here is a bit of discussion on the CEO/CTO relationship.”

Whitney Melendres reflects on personal struggles in this area:

“I am in a co-director role of a non-profit and finding it difficult to come to agreements and push through relational conflict. I do believe that two are stronger than one, however I’ve also heard it said that there are no creatures with two heads for a reason.”

Is it really about one partner being highlighted more than the other or do we simply have different resources we each bring to the table that elicit different responses? What is the role of luck? How might flat organizational structures or split leadership models be used to successfully take advantage of unique strengths across the organization? We want to continue this dialogue. Tell us what you think.

We enter this world alone … and we leave this world alone. However, I am a village. I pair all the time with whoever is standing in front of me, what I see and hear or read. This whole conversation is nonsense … A group masterbation.

Ron Hartgrove