It makes me happy to welcome back my good pal Nick Rabkin to Dewey21c. –RK

The Three Horsemen of Arts Education

by Nick Rabkin

I’ve done research on teaching artists for the last three years—from Boston to San Diego—at NORC at the University of Chicago. (My report is available for download at NORC’s website.) The creativity, commitment, and accomplishment of many, many TAs has impressed me, and I’ve been encouraged by growing efforts in many communities to develop arts education more systematically and make TAs part of the strategy. I’ve also been disturbed by the paucity of validation, the stress (and even deprivation) they endure to make a life as artist/educators. Half have master’s degrees, but most make less than $10,000 a year from teaching. The proportion without health insurance exceeds the national average by a third. Despite the challenges, I found that the best of them are forging innovative, democratic practices and ideas about arts education and learning that are making a real difference to students, have profound implications, and enormous potential.

So I have wondered, what’s the problem? Why are they so marginalized?

The biggest reason is that the arts themselves are marginalized in education. I spent a good deal of time investigating why that is so, since it seems clear that the destiny of teaching artists is entirely bound up with the fortunes of arts education. There are three big reasons. We might think of them as the three horsemen of arts education, just one short of an arts ed Armageddon.

1. School reform: A Nation at Risk, the report that launched the school reform movement during Reagan’s presidency, argued that our schools had lost their focus and lowered their standards. Manically mixing metaphors, the report saw a ‘rising tide of mediocrity’ in schools that substituted ‘appetizers and desserts’ for ‘entrees’ and endangered our nation, like an ‘unfriendly foreign power’s “act of war.’ Ignoring the arts, it implied that arts education was a ‘dessert,’ inessential to a quality education, and part of the problem. It set a strategic template for school reform that still dominates educational policy.

But why did A Nation at Risk dismiss the arts? I speculate that has to do with widely and deeply held beliefs, misconceptions actually, about the nature of the arts and the nature of learning: First, a belief that the arts are emotional and expressive, not cognitive and academic. This belief, in turn, is grounded in the classical concept of the mind—that conscious, rational thought is fundamentally different and of a higher order than feelings, emotions, and sensations. Modern cognitive and neuroscience has shown that this model of the mind is fundamentally wrong, and that thinking, feeling, and our senses are all functions of the same integrated nervous system. In fact, we can’t think in the absence of emotion and sensation, and most ‘thought’ is fundamentally unconscious. This emergent model of the mind suggests that art—which lives in the connections between thought, feeling, and sensation, and which involves connecting the unconscious to conscious awareness—is profoundly cognitive. Nonetheless, our ideas about learning and the ways we have structured education are rooted in the old model, what neuroscientist Antonio Damasio has called ‘Descartes Error.’ (Check out Damasio’s book by that title, and Metaphors We Live By and Philosophy in the Flesh by cognitive linguists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson.) That error is undoubtedly confounded by the strong strand of anti-art Puritanism in our national DNA.

2. Fiscal crisis: By the late 1970s the transformation of the American economy that has proven so destructive to our national prosperity—the steady decline of manufacturing, the export of jobs from the US, and the explosion of debt—was already damaging the financial stability of school systems around the nation. New York City had a fiscal meltdown in 1975, and the school system was a major victim of President Ford’s vow to veto a bailout, resulting in the legendary headline above. Arts education was one of the first targets for deep cuts. Chicago laid off all its elementary art and music teachers in 1978, during a fiscal crisis.

3. Tax rebellion: The ‘Reagan Revolution’ was based, in large measure, on a deep resentment of government, often fueled by a misguided belief that the only beneficiaries of government programs were corrupt politicians and the undeserving poor—usually folks with darker complexions. Proposition 13 was passed in California in 1978. It restricted the capacity of local jurisdictions to raise taxes to pay for public services, including education. California schools continue to suffer, and the tax rebellion has become a sustained principle of American politics. Conservatives promote a ‘starve the beast’ (beast=government here) strategy today, and public education (teachers, in particular) is a prominent target. Despite formal designation as a ‘core’ subject, even Democratic administrations that speak to the value of creativity in education, tend to target arts education for cutting.

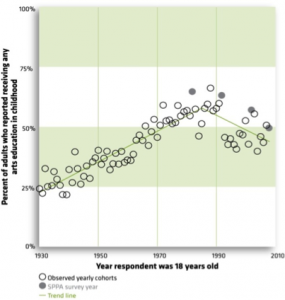

These three horsemen have done very substantial damage to school-based arts education. Earlier this year, the NEA released an analysis of data from their Surveys of Public Participation in the Arts that showed a long and steady increase in arts education reversed in the early 1980s, as they all kicked into high gear.

The graph shows that childhood arts education rose from less than 25% of all children in 1930 to a peak of about 65% in the early 1980s, when it began dropping. By that time, school reform, fiscal crisis, and tax rebellion were all underway. The rate was below 50% again by 2008. Most of the decline has been in music and visual art, the disciplines most frequently offered in schools. The rate for white children has not dropped substantially, but the rates for black and Latino children have declined steeply. Simple deduction leads to the conclusion that most of the decline is centered in schools that serve those student populations, and many of their schools have become virtual arts deserts (no, not desserts!).

Needless to say, schools serving those children are in the cross-hairs of school reform efforts that dismiss the arts.

If school reform was meeting its objectives—closing the achievement gap, improving US students’ standing on international tests, raising standards, and preparing all students for higher education and work in the 21st century—the case for making arts education a strategic element of school reform might quickly be closed. But last week a new report from the Consortium for Chicago School Research showed that more than two decades of determined efforts to ‘reform’ Chicago schools has had very limited results. It showed that reports of test score improvements were actually the effect of changes in the tests themselves, not higher student achievement. The racial achievement gap actually widened across the district. Similar findings deflated test score results in NYC last year. Large-scale cheating on standardized tests has been uncovered in Philadelphia, Washington, DC, and Atlanta. Analysis of international tests shows that the US has fallen farther behind more nations in more subjects. This pattern demonstrates that school reform is not succeeding on its own terms, not meeting its objectives. That is a tragedy for American students and the country. The only upside in recognizing the pattern is that it may open the door to ideas about improving schools that include the arts.

Nick Rabkin

Nick Rabkin’s career in the arts began with work for Chicago’s Organic Theater Company, producing new works for the stage. He was also deputy commissioner for cultural affairs for the City of Chicago, and the senior program officer for the arts and culture at the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. He was the director of the Center for Arts Policy at Columbia College Chicago for seven years, and is now a senior research scientist at NORC at the University of Chicago and a research affiliate of the Center for Arts Policy at the University of Chicago. Throughout his career he has been particularly interested in the ways that the arts contribute to the quality of democratic life – especially with regard to social relations, development, and education. He’s written widely on arts education, including the book, Putting the Arts in the Picture: Reframing Education in the 21st Century. He expects to complete the first large-scale study of teaching artists in a dozen communities – from Providence to San Diego – in the near future.

Amen

…and thank you:)

Nick, An insightful analysis of many of the historic trends leading to declining funding and lessening emphasis on arts education. There have been many journalists, authors, researchers writing these days about the “creative economy” and the need to educator our students in creative skills for the future, writers like Daniel Pink, Richard Florida, Douglas Thomas, John Seely Brown, Cathy Davidson, and Thomas Friedman. I wonder if any of these ideas are beginning to take hold in the larger society. Is it possible we’ll see a shift in the future towards a greater value on creativity and therefore the unique role the arts might play in learning?

As a casualty of “educational dietary practices,” (ie, they cancelled dessert….. and, hence, my career as a professional teaching artist!), I read your article with bitter sweetness. The “sweetness” was in the truth it contained. That educational policy-makers continue to make demands on the minds of our students, without nourishing those minds fully ( which of course, includes the neurological connections provided through the arts) continues to reap substandard results. And one would hope that the “upside” of the downside does include a revisiting of the role and power of the arts, as you mentioned. However, as I think of the reality of the iconic public school that I face each day, ( it is the icon of “Underfunded, Un-enlightened Public School”), the “bitterness” of truth unheeded depresses me a bit. There is always hope, however, as long as enlightened educators like yourself continue to fight the good fight. Maybe someday I will be able to return to my “first love”…. and actually make a living at it! For now, it’s good to know you’re out there — hoping, fighting for our kids’ minds, and transforming the “menu” so that arts education can take its rightful place as a “main entree!’

Nick (and Richard),

Thank you for the straight-on blog and for the tireless work of getting that study to completion. The first study of teaching artists, filled with good and disheartening news–I recommend it to all. The three horsemen image is pretty daunting. Come back and blog about the ways you think we might stave off the emergence of the fourth horseman, if you think that is possible.

Just got to this post, Nick and all…it’s a fine distillation of our history and what struck me hardest was your sentence:

‘That error is undoubtedly confounded by the strong strand of anti-art Puritanism in our national DNA’ –

Long ago I came to the conclusion that most Americans don’t give a fig for the arts as education…

Thanks for your clarity and focus…

Jane

Great post, Nick! Thanks.

Here’s a question :: why do you think that we can keep making these logical arguments but still receive little attention or appear to make less progress than we should?

John – The reason is that logic doesn’t have as much to do with it as our feelings and mental models of the arts – they are more powerful than logic. We need to keep asserting the logic of our case, but we also need to understand why people feel as they do about the arts. I think the Puritanism thing has something to do with it. I think Descarte’s error does, too. I didn’t mention, though, that I also think that American politics since Nixon has been such a game of resentment, and I think many Americans resent the arts. They see it as a priviledged domain that they do not share in or participate in. And they are not wrong. The stuff they like is dismissed as ‘inferior’ and the stuff they don’t like is revered as ‘important’.

Nick,

How good to be in contact again! What a treat. Drop a note whenever you can so we can catch up a bit.

All good wishes,

Leonard

A compelling and sobering post, Nick. I like your big-picture analysis of that first horseman: our bias against the arts is rooted in “the classical concept of the mind—that conscious, rational thought is fundamentally different and of a higher order than feelings, emotions, and sensations.” You mention Damasio and Lakoff & Johnson, and I would add David Brooks’s The Social Animal, which makes a similar argument based on even newer research. I look forward to reading your report…

I am teaching at Hamilton Elementary, an arts magnet–and am impressed with the high level of thinking I see in the kids across all ages in a school that foregrounds the arts.

And isn’t Steve Jobs a huge example of creative thinking? I wonder what kind of arts education he had…

Hi Ginny!

Watch Steve Jobs’ commencement speech at Stanford–he talks eloquently about how his art education informed his life.

Nick:

Still on the case, Huh? I’m glad that you are. I have become interested in in how Middle School education is such an important moment in the lives of our children. I interested in useful definitions and descriptions of the 21st century Middle School classroom. Reading these works provide additional ways to consider it.

Best

Maintain the Strain

george

Nick: Nice piece.

In another version:

War — internecine fights among among cognitivist and aestheticist arts enthusiasts that deflect the national discourse about arts education.

Famine — well, starvation by budget. Or undernourishment of our children’s souls.

Pestilence — Republican party hoards wandering the nation without supervision.

Death — the knell of programs falling to the block.