Relevance.

It’s quite the loaded term in the arts and arts education fields, don’t you think? I was once talking with two colleagues and the topic of jazz came up. One friend said that she didn’t think that jazz was relevant. The other friend had a cow, as the saying goes, wondering exactly how such a statement could be offered.

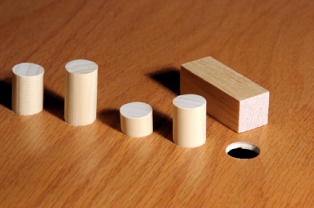

To many in the arts, relevance is established through a transcendence of the art, that is too often in the mind (and heart) of the beholder or a shared by relatively small group of cognoscenti. Matters of popularity are relatively unimportant, for how can one possibly compare Justin Bieber to Miles Davis or Bach.

That was, in essence, what my other friend offered as a response to the question of relevance: that jazz is an expression of the human condition, that it feeds our souls, and enriches our lives. Thus, it is relevant in a way that transcends temporal matters such as box office sales (or whether or not anyone is listening). And, for that reason, it is worthy of government and private funding.

Does it sound familiar?

Today, there is a massing of challenges to the arts the likes of which we have not seen before, outside of the pure market forces which dispose of the lauded TV shows that fail to gain a big audience, or days gone by when entire forms like Vaudeville where killed by changes in taste and technology, even though the essence of Vaudeville lives on, having woven itself through many current forms.

I would bet that most people in the arts, if pressed, would say that the challenges are coming from conservative Republicans, who seek to defund the NEA, NEA, CPB, PBS, US Department of Education, and more. And while that may be true, it’s a much more crowded and diverse field than many realize. You have Robert Reich and Paul Krugman (two of my heroes!), questioning the charitable status granted major arts institutions. To them, the major institutions are elitist, catering to tax breaks for the wealthy, hardly a charity.

You’ve got Bill Maher stating that the arts are “nice but not essential.”

You’ve got the elimination of Grammy categories propelled by complaints from those in the record business who feel that the Grammy Awards are out of touch, as evidenced by Esperanza Spalding being selected over Justin Bieber for best new artist. In other words, those who run and heavily influence the Grammy Awards have questioned the relevance of less popular forms. And you know what, they’ve succeeded in getting quite a few categories either diminished or dropped from the awards program.

And don’t forget, there’s the Obama’s deficit commission, Erkine-Bowles, which is calling for a limit on the amount someone can deduct from their taxes for the purposes of charitable contributions. While this proposal is not specifically focused on major arts institutions, a la Reich and Krugman, if enacted it would have seismic effects upon the entire non-profit sector, including the arts.

Let us not forget the great paradox that many feel about arts education. On one hand there are many in the arts world who want to see greater access to quality arts education in the public schools, based on a belief in the importance of such experiences in a child’s life, while also believing that greater access leads to greater participation (butt’s in the seats!). At the same time, what ultimately inhibits greater access to quality arts education is a matter of relevance. The great policy hurdle is really a matter of perceived relevance.

What exactly is there to do, when relevance is measured by many as whether or not tweens download a CD or watch a particular show on Nickelodeon? I get it, I really do, that this issue is nothing new. That being said, it’s quite the brew, when you have the Philadelphia Orchestra declaring bankruptcy, government funding on the precipice, long-standing models of dissemination and creation upended through the ever increasing pace of change in technology, where one day it’s MySpace, the next it’s Facebook, followed by who knows what! Add to that an NEA Chairman who arguably places the agency in harm’s way by publicly musing about whether there is too much supply and not enough demand, and well, you’ve got to admit there’s a dynamism at play here, the likes of which we have never quite seen before.

So, what is there to do about the fluidity of our times and the questioning of relevance?

Well, first, I think it’s important to recognize that as a field, we haven’t done a great job of communicating the importance, and yes, the relevance of the arts in America.

At the same time, It is not a bad thing, mind you, to admit that there are some things that we can do little about, which are the sorts of trends, changes in tastes, generational shifts that cannot be halted, even though there is always a call for that public service campaign to magically redirect a shifts or two in favor of a particular art form or genre.

I do find solace in many of the ways artists are ignoring the tracks laid down by previous generations, choosing instead to jump those tracks at will, while helping to redefine what we have come to know as for profit, non-profit, traditional, education, community, and service.

It seems to me that it is these artists who will reshape the context for what creates and defines relevance. As older organizations and structures fail, new will emerge, a bit like what happened after the 1988 fire at Yellowstone, where the scorched landscape was renewed in surprising and wonderful ways.

To help it along, we need to remain open rather than closed minded about change, encouraging experimentation, providing support, and finding thoughtful ways to reflect on the meaning and potential of the experimentation, as a living world of arts should, thereby engaging in what Maxine Greene calls “making meaning,” for it is within such making of meaning that the reshaping of relevance will emerge.

Labeling an art form “irrelevant” is small-minded.

As arts leaders, the question shouldn’t be whether the arts are relevant, rather whom are the arts relevant to, and how do we expand that population.

If the arts were intended to be relevant to as many people as professional sports, we wouldn’t need public funding and donations to support them.

Excellent post. As an arts advocate I’m helping prepare my community for Arts Advocacy Day – April 27th. In Washington, D.C. local arts funding is now 1/3 what it was three years ago. The arts are within the development budget and what we keep hearing is, well, all development spending is down. The public, and the politicians who follow them, see that there will always be justin bieber and dancing with the stars, so why do we need ballet and the orchestra? We’ve known that audiences are graying for years. Your piece hits the nail right on the head about the need to establish the relevance, or value, of non-profit (can I say i.e. classical?) arts versus the for profit forms.

Kessler says: “Well, first, I think it’s important to recognize that as a field, we haven’t done a great job of communicating the importance, and yes, the relevance of the arts in America.”

I wonder if we could define “relevant” in this context. Because I believe the arts are more relevant and more important to more people than, say, sports are. It’s just that those who “provide” the instruction (I’m one of them – happen to be in music education) have chosen to ignore the meaningful, relevant, art forms to the different cultural groups in our society and instead “push” our white, elitist, Western European art music as if it is what all should strive to know. It is interesting that you bring up jazz. That jazz music is not REQUIRED as a form of American music history in all of our conservatories (much less public schools) is a real mystery to me. Why have we chosen to ignore/oppress jazz (for instance) in schools and Schools of Music? (oh I know, it’s “there,” but almost always on the periphery). This is a great topic. Thanks for bringing it up. And by the way – I love this blog.

I’d like to see more talk about the way arts and artists serve their communities and engage their communities. (I don’t mean “outreach,” I mean what effects does the art have.) As a classical musician, I find that much music aims to please and impress others in the music business. It’s as if the audience eavesdrops while professionals sing for each other.

I think our society needs the arts very much right now, and needs art to speak not just to other arts professionals but to everybody, because the culture and the species are on the cusp of huge changes. (As Daniel Quinn has said, the next few years will be amazing, either because we change our way of living or because we don’t.)

One way to think about “relevance” is that arts and artists should have an effect on the local community–not the community of arts professionals, but the neighborhood and the watershed. I don’t mean the economic impact, but the impact on the community’s understanding of itself, its emotional well-being, its compassion, its ability to concentrate, its sense of connection with other times and places, its sensitivity to beauty, its capacity for awe, etc. Does the art maintain divisiveness? Does it bolster enthusiasm? Does it contribute vitality?