A lot of attention has been paid to the recent report commissioned by the arts endowment: Arts Education in America: What the Declines Mean for Arts Participation.

I thought it would be a great opportunity to pose some questions for the author, Nick Rabkin.

Let’s just say that rather than leave interpretation to others, that it’s always best to hear directly from the horse’s mouth.

Many people are seizing upon this report as a sort of smoking gun for how cuts to arts education lead to cuts to arts participation, and conversely how increasing access to arts education would lead to an increase in arts participation. Presumably, it’s a good part of what Rocco Landesman was using as a research based rationale for urging arts organizations to increase arts education. In this instance, it was a prescription for increasing demand.

I have known Nick Rabkin for many years and am a big, big fan of his work. I am really glad that he was able to take the time from his busy schedule to answer a few questions. –RK

*************************************************************************************************************** March 2011, Q&A With Nick Rabkin

1. What were your research questions?

The NEA’s SPPA surveys have tracked adult participation in the arts since 1982. The NEA is particularly interested in attendance at what they call “benchmark” events–mostly performances and exhibitions presented by not-for-profit arts organizations–but the surveys track some other forms of arts participation as well, including arts education. The NEA commissioned my study and several others because the data shows that the rate of benchmark attendance has declined pretty significantly since 1992. That’s a deep concern to the not-for-profits and the NEA, and it is probably what prompted Chairman Rocco Landesman’s recent remarks about lagging demand and oversupply in the arts.

Our first question was to determine the strength of the relationship between arts education and adult participation in the arts. How strong is it? And has it been consistent over time across all of the SPPAs? Second, we wanted to probe the data to see if we could better understand what has happened to arts education over time. Has arts education had declined along with other forms of participation over the years? Some recent studies have suggested that increasing arts education might be vital to strategies to increase arts participation, so our third question was about whether there was evidence in the SPPA data that supported that idea.

2. What were your main findings?

We found that arts education is the single most powerful “predictor” of adult arts participation. Other variables, like educational attainment and income also had strong relationships to arts participation, but none had a stronger association with benchmark arts attendance or with personal creation or performance than arts education. Note that I’m using the word “predictor” here, not “cause.” More arts education as a child or as an adult makes it likelier that people will participate in the arts as adults. That statistical relationship suggests that arts education is a contributing cause of adult arts participation. This finding is significant, but not a big surprise. It important to recognize that many, many influences contribute to adult decisions to participate in the arts.

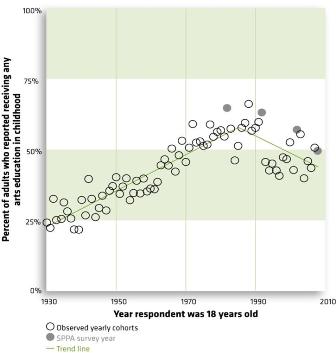

All the SPPAs asked questions about people’s experiences with arts education as children. We looked at the proportion of 18 – 24 year-olds who reported that they had any arts classes or lessons (in-school or out) before they turned 18, and found the proportion had declined in each survey–from a high of about 65% in 1982 to under 50% in 2008, a serious drop. Since the surveys covered a representative sample of Americans, including older Americans, they included data about childhood arts education that went back long before 1982. We found the proportion that had classes or lessons as children had risen steadily from 1930, when less than 25% had any arts education, until the early 1980s, when the proportion began declining. Access to arts education rose for American children by about 180% from 1930 to 1985. It has declined by a quarter from 1985 to 2008.

(Note that those dates refer to years in which survey respondents turned 18. Their childhood experiences occurred prior to those years, of course. So the decline in childhood arts ed began before 1985 – probably in the 1970s, when fiscal crises in most major school districts and taxpayer resistance to public services like education combined to force deep cuts in school districts across the nation.)

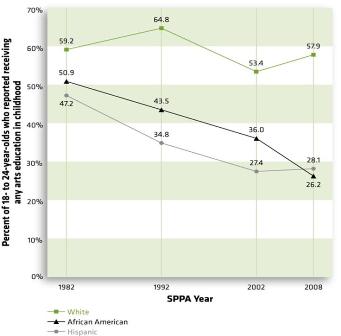

When we looked at how that decline was distributed among American children, we found that most of the decline has been concentrated among African American and Hispanic children. There was only a small decline among white children.

When we examined how the decline was distributed among art forms, we found that it was concentrated in visual art and music, the two arts forms most frequently taught in schools. (In fact, there were small gains for both theater and dance, which are both mostly taught outside schools.) So the data shows that most of the decline in childhood arts education has been in schools, and most of that has occurred in schools that serve minority children.

3. If participation in K-12 arts education is a strong predictor of adult arts participation, why wouldn’t declines in access to arts education be a contributing factor in declining levels of arts participation? What is wrong with that assumption?

I think the argument holds water, but I also believe that the effects go in both directions. In other words, education policymakers who do not themselves participate in the arts are probably less inclined to value arts education and make policy that supports it in schools. The relationship is dynamic and bidirectional, not linear.

4. Is the strategy of audience development through arts education is problematic?

Well, it is certainly problematic if you are looking for a quick turnaround. But it should be a foundation for any strategy that looks to the long term, though. That is easier said than done, since the long-term decline in arts education does not appear to be slowing down in this recession. What’s more, the trends in school reform for over thirty years have not been friendly to arts education. Intense focus on high stakes standardized tests and punitive accountability have narrowed curriculum and made it more difficult for good principals and teachers to carve out time for arts education. So the problems for the arts and arts education are linked in a vicious cycle. It will be hard to break that cycle until education policymakers realize that the basic strategies of reform have not moved the needle for student achievement and that we need to (finally) grow beyond the old factory model of schooling. There are emerging and hopeful signs that could be starting to happen (and some less hopeful signs that the recession and fiscal crisis are constraining creative impulses in education policy).

5. Most of the available research around the status of arts education is based upon what is offered, as opposed to what students actually receive. What were you able to determine regarding what is offered and what were you able to determine regarding real levels of student participation? Do you believe this distinction is important?

That’s what makes the SPPA data so valuable. It actually shows how many Americans took arts classes or lessons as children and as adults, not whether the schools they attended offered classes. That is a more accurate way to measure what matters – whether students are getting access to arts education.

6. Did the data reveal anything about how and when the arts education was delivered? For example, in-school by certified art teachers or by teaching artists? Or out of school time?

The SPPA data is limited and not very granular, so we can only see broad trends in it. In some survey years there were questions about whether people had taken their arts classes in school, out of school, or both. That is how we know that nationwide music and visual arts are offered far more than theater and dance in schools. But some surveys did not ask where the classes were. And none of the surveys asked people about who taught the classes, or the intensity, longevity, or quality of the experiences. We might speculate that longer and better instruction would have a stronger association with future participation, but we only know if people had “any” classes or lessons in music, dance, theater, visual art, or creative writing as children. We can’t distinguish between someone who had ten years of private lessons on the clarinet and someone who had six weeks of recorder lessons in their fourth grade classroom. They both could answer ‘yes’ to the question on the survey.

7. What do you think is the importance of this report?

Most advocates have believed that there has been a long-term decline in arts education for children, and we’ve had much anecdotal evidence of deep cuts in many districts, but there has been no reliable record of the picture across the country. Some have speculated that there were increases in arts education during the 1990s that were rolled back when No Child Left Behind became the template for national school policy. The NEA

s Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (SPPA) data gives us very strong statistical substantiation that arts education has been a major casualty of school reform and budget cuts, that the damage began in the 1970s or 80s and continued through the 90s. All of the effort to develop arts standards and establish the arts as a ‘core’ subject in the 90s did not change the downward trajectory, and NCLB sustained the long trend. Since the biggest victims have been low-income minority children in schools where they are concentrated, arts education is an equity and a civil rights issue. (Thanks for making that point in your blog post, Richard.)

The report also proves that there is a very powerful relationship between arts ed and participation. That is most important to arts organizations that present the arts and to artists, but it doesn’t cut it as a reason to change educational policy. There is a growing body of terrific research that shows the power of arts education to improve student performance and motivation in schools. We need to learn from it, build on it, and use it to demonstrate to policymakers that arts education can help them solve the problems that keep them awake at night.

8. When will your report on the state of teaching artists be released, and are you as excited about it as almost everyone I know is?

Thanks for asking. No one is more anxious to complete that study than I. We’ve collected a mountain of data – 3500 surveys and over 200 in-depth interviews in a dozen communities across the country. Most of the analysis is finished, and I’m writing feverishly every day. I hope the finished product will be available in two or three more months. Here’s a preview: Teaching artists are important in communities and schools everywhere. They offer essential and in-depth arts ed resources for young people that schools will never be able to provide. Especially since the 1980s and 90s, they have been bringing fresh insight and practice into arts education in schools, exactly the kind of innovation that need badly if they are to become more dynamic places for learning. Stay tuned. More to come soon.

Childhood arts education rates, 1930 – 2008

Arts education rates by race, 1982 – 2008

*************************************************************************************************************

Nick Rabkin’s career in the arts began with work for Chicago’s Organic Theater Company, producing new works for the stage. He was also deputy commissioner for cultural affairs for the City of Chicago, and the senior program officer for the arts and culture at the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. He was the director of the Center for Arts Policy at Columbia College Chicago for seven years, and is now a senior research scientist at NORC at the University of Chicago and a research affiliate of the Center for Arts Policy at the University of Chicago. Throughout his career he has been particularly interested in the ways that the arts contribute to the quality of democratic life – especially with regard to social relations, development, and education. He’s written widely on arts education, including the book, Putting the Arts in the Picture: Reframing Education in the 21st Century. He expects to complete the first large scale study of teaching artists in a dozen communities – from Providence to San Diego – in the near future.

*************************************************************************************************************

blog | AJBlog Central | Contact me | Advertise | Follow me:

blog | AJBlog Central | Contact me | Advertise | Follow me: