The New York Times recently published a feature story on the state of concert music freelancing: Freelance Musicians Hear Mournful Coda as the Jobs Dry Up.

It was a good living. But the New York freelance musician — a bright

thread in the fabric of the city — is dying out. In an age of sampling,

digitization and outsourcing, New York’s soundtrack and

advertising-jingle recording industry has essentially collapsed.

Broadway jobs are in decline. Dance companies rely increasingly on

recorded music. And many freelance orchestras, among the last steady

deals, are cutting back on their seasons, sometimes to nothingness.

It’s not as if I didn’t know the story well, but I do have to say that there was something about reading (and watching the videos) that took my breath away. I thought Daniel Wakin did the story justice.

I have felt for quite some time that the forces conspiring to diminish the field of concert music are forces that are much more complex, difficult to understand, and perhaps impossible to alter than most people might believe, particularly when folks like to place the blame on easy targets such as a lack of music and arts education in the schools.

I was glad that the article presented some salve, perhaps hope even, in the ways in which younger artists in particular are becoming more entrepreneurial, adapting to and trying to seize opportunities in the changing landscape.

I do have a reflection to add to the story, maybe you could argue that it’s an extension really.

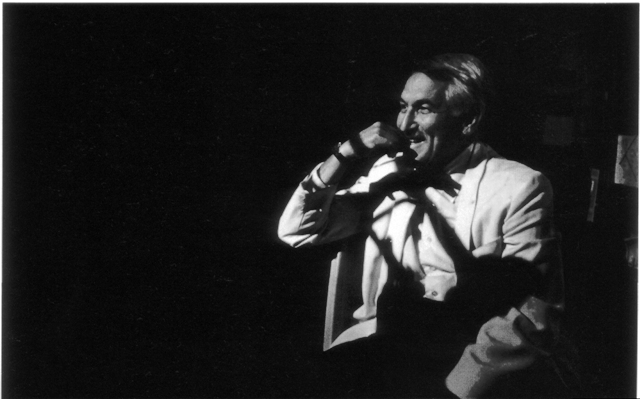

I tend to view this issue, the decline of the concert music life for professional musicians, through three different periods: the 1950’s, the 1980’s, and today. It is framed by something said to me by a teacher, mentor, and dear friend, Gilbert Cohen, who played second trombone for the New York Philharmonic. That’s Gil, second from the left, in a picture of the New York Philharmonic low brass section, circa 1964.

Near the time I was to graduate Juilliard, Gil Cohen, whom I had first met at a side-by-side concert with The New York Philharmonic and The NYC All-City High School Orchestra (we were both second trombones), later becoming close friends, said to me: “I worry about young guys like you coming up. I just don’t see much of a career to be made.”

Near the time I was to graduate Juilliard, Gil Cohen, whom I had first met at a side-by-side concert with The New York Philharmonic and The NYC All-City High School Orchestra (we were both second trombones), later becoming close friends, said to me: “I worry about young guys like you coming up. I just don’t see much of a career to be made.”

Gil went on to talk about what it was like when he was freelancing in New York City during the 1950’s, prior to joining The New York Philharmonic.

He then turned his mind towards today, keep in mind that the “today,” that day or period, was approximately 1983. He said that the field was a fraction of what it had once been in comparison to the 1950’s, and wondered how young players would make a living, in light of the number of graduates and the reduced field. Unless you got a major orchestra job, he said he worried, and everyone knows how hard it is to get such a job.

Fast forward to 2010, and the article in The New York Times. If you read the piece and don’t know the story Gil Cohen told, you might get the impression that the decline has been something less than gradual, something that hasn’t been ongoing for the past fifty years.

For these types of musicians, who play this music and these instruments, Gil Cohen paints story paints a much longer term picture. I would argue that what’s happening today is an erosion that has reached the most top level freelancers, who may have been protected, to some degree, by the declines since the mid-20th century.

Don’t get me wrong, I do recognize the the musical life in the United States is much more varied than it once was. There are more smaller productions, more new music, and artists are creating their own to replace such things as a record industry, artist management, etc. There is a wider array of styles and forms, and the field has expanded to include the teaching artist. But, if you’re a classically trained trombonist, clarinet player, etc., well, the Times piece by Daniel Wakin is certainly something you understand all too well.

Can the changes be stopped, slowed down, or altered in any way? Has it hit bottom or leveled off? I tend to think not, for I believe the forces at play are not malleable. Sure, the musicians union can stave off having Broadway producers going to fully synthesized pit orchestras. But, can the union bring back the number of shows during the hey days of Broadway that used pits full of orchestra players. It’s doubtful at best.

Great post- I remember flutist Andrew Lolya telling me about how union musicians used to be categorized- Ballet, Broadway, Symphony, etc- as there was so much work that it was sectioned off in some way. For certain instruments by the time we got to the 80’s there was a limited amount of work, and now less. Is it going to change? Probably not in the way we might imagine, but you never know! Could the public rebel against increasingly synthesized sound? Only if their ears can recognize the difference….!!

A tangential or parallel problem has been the almost complete collapse of amateur classical music making beyond the grade school level. Everyone wants their kids to learn an instrument but 99% of those kids stop playing by the time the go to college, in part because of time but also because there just aren’t many opportunities. The opportunities for adults to play classical music on an amateur level are almost non-existent.

Flash back to 50-75 years ago and there vastly more of this happening on many levels. I had a great uncle who was a CEO of a pretty big company and he would dash home for lunch regularly so that he could play string quartets with other amateur friends. They’d grab bites of their sandwiches between reading movements of Haydn, Beethoven, etc. At the end of the hour, he’d dash back to work for the afternoon.

I bet you could count the number of string quartet playing CEO’s on one hand these days, and you’d probably have fingers to spare.

These adult amateurs were also a key audience for professional musicians. So while music education for kids is vital, let’s not forget about the adults. By providing opportunities for amateur adults, I’d be very surprised if we didn’t create more opportunities for the professional freelancer as well.

Could it not be that we as musicians, have turned the corner and the circle has been completed? To understand this one needs to look back to the work that was available to musicians in the 1600’s and beyond. A lot of that work was generated for the musician by wealthy patrons, or in playing for smaller more intimate does in salons.

Maybe in this future that is evolving, there will be more work for musicians than we could ever imagine, but just not in the larger forms that we have come to expect. People may not be as interested in attending a larger concert performance, but if a smaller version of the orchestra, or string quartet or ??? is there playing for a wedding, christening, 21st, 50th, 100th??? it could be very successful and desirable.