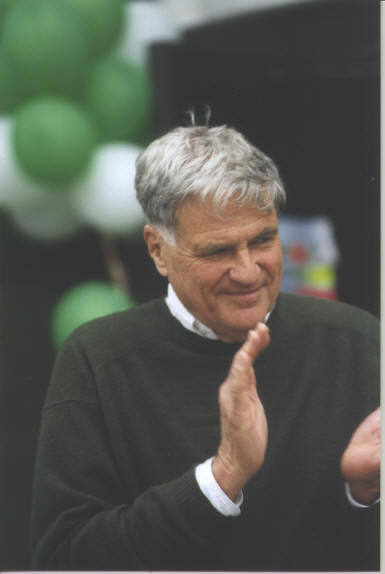

At Dewey21C, It would be impossible ignore the passing of Ted Sizer, one giant of an educator. You see, Sizer was considered by many to be the heir to John Dewey.

There will be obituaries everywhere, as well as tributes. He footprint was all that.

I never had the privilege of meeting Mr. Sizer, but have read and been inspired by his work and vision, a vision that always seemed to reflect the complexity of what was at hand. And today, in so many ways, remains a counter-balance to the technical solution variant of school reform so evident all around us.

At the Center for Arts Education, Sizer’s thinking was evidently behind so much of the first decade of work in school partnerships. This was work, in my humble opinion, that reshaped and reframed the entire notion of school partnerships with arts organizations (and post secondary institutions).

The work was based upon the needs and interests of local schools, and was not determined by one curriculum, framework, or blueprint–no matter how well liked or politically connected the document was. Guiding principles were established to provide some coherence, but in the end, the school community and its partners determined much of what they would do and where they would go.

This was all fueled by The Annenberg Foundation, which also fueled the Annenberg Institute for School Reform. While much of the school reform world likes to trash the Annenberg Challenge as one colossal failure, they don’t often bother to look at the work of the three Annenberg Challenge organizations devoted to arts education. It’s as if it doesn’t really count. In many respects, that is a metaphor for the very place of arts education in schools then and now, and a good guide as to where we need to drive to as a field and hopefully one day, a movement.

Sizer was heading up the Annenberg Institute for School Reform, and naturally, his work and principles had an effect on the thinking of my very fine friend and colleague at CAE during this time: Hollis Headrick, Greg McCaslin, and Russell Granet, among others. Whether by explicit design or lurking in the background, the connection to Sizer is difficult to deny.

My takeaway about Sizer is that he was ultimately about the art and craft of education, and that was and will remain, refreshing, instructive, and central.

I have thought a great deal about quality of conversation. It is something I have been wanting to blog about. It is something I want to capture better, as a way of measuring, understanding, and communicating. What I mean specifically is how I am often deeply moved by the ways in which the quality of the conversation illuminates the development of understanding, shared language, individual and collective capacities, learning, programmatic objectives, skills, and so much more. It would be fair to say that it’s the polar opposite of the standardized test.

And it makes me think, so very much, of the work of Ted Sizer.

I leave you with a a group of quotes:

It is an inescapable reality that students learn at different rates in

different ways.That creates the need for a schedule of sensitivity that

not only teachers close to the particular student can devise – not some

theory-driven, central office, computer-managed schedule.

‘We parade adolescents before snippets of

time. Any one teacher will usually see more than 10 students and often

more than a 100 a day. Such a system denies teachers the chance to know

many students well, to learn how a particular student’s mind works.

Only by examining the existing compromises in schools, however painful

that may be, and moving beyond them, can one form more thoughtful

schools. And only in thoughtful schools can thoughtful students be

hatched. And this requires thoughtful leaders.

Schools are complicated places. Attitudes - those of teachers, students and others - must change as well as the structures of the schools in which they work. This takes time, political protection and patience.

When the students forget the explicit contents of today's lesson - and we know that they will - what is left? Anything? What happens after they forget the difference between atomic number and atomic mass? What is left after they forget the difference between the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights? After they forget the rhyme and scheme and meter of a Shakespearean Sonnet or between sin, cos and tan?

Respect for students starts with respect for teachers, for them as individuals, for their work, and for their workplace.

Thank you for sharing these quotes. I am a teacher today in no small part due to a course with Ted Sizer in 1986 on high school in America, so I am sharing these with my students today and remembering Ted Sizer fondly.