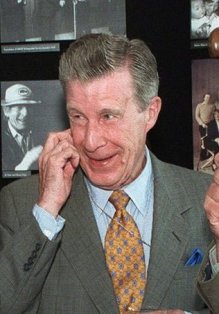

My friend Schuyler Chapin died last Saturday. Perhaps you didn’t know him. Perhaps you didn’t know much beyond his tenure as New York City Commissioner of Cultural Affairs or saw him interviewed in a documentary about Leonard Bernstein. Maybe you read one of the obituaries.

All the aphorisms about Schuyler are true: the end of an era; he broke the mold; a true gentleman; lived a charmed life; and yes, I could go on.

The career Schuyler had, well, I just don’t think it could be possible today. In an era when people did not reinvent themselves and move from job to job, career to career as they do today, Schuyler was the doing it and doing it big time.

The career Schuyler had, well, I just don’t think it could be possible today. In an era when people did not reinvent themselves and move from job to job, career to career as they do today, Schuyler was the doing it and doing it big time.

Essentially, he started out as Jascha Heifetz’s road manager. In a relatively brief amount time he headed up Artists and Repertoire at Columbia Records. He was right there at what was the beginning of the true golden age of recordings. Under Columbia, you had Ormandy, Bernstein, Szell, all making volumes and volumes of recordings. He was there with Horowitz, Stravinsky, Glenn Gould, and countless others.

From Columbia he went to Lincoln Center, as the first head of programming at the first performing arts center of its kind in the nation.

Much has been written about his time at the Metropolitan Opera and at the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs. But, it is his work with and for the many artists, and the many friendships and important relationships that he had that was the mark of this great man. His important friendship with Leonard Bernstein. His support for the career of Dimitri Mitropoulos. His friendship with the great music patron Francis Goelet. Schuyler’s touch is clear throughout the philanthropy of Goelet. These are just a couple of examples from a list that is too great to count.

A number of years ago, I read a biography of Dimitri Mitropoulos, the great mid 20th Cenury conductor and music director of the New York Philharmonic. Studded throughout the book is Schuyler Chapin, who managed Mitropoulos at the time. It becomes abundantly clear that Schuyler was more than a manager: he was helping Mitropoulos navigate his way through his complicated career and personal life.

Schuyler was always there when you needed advice and always found a way to help. I once went to him for career advice after just starting at The American Music Center. Things were so very rocky at that time and I was very worried.

He told that he had a story for me that he thought would be helpful, which I remember very, very well: when he was at Columbia Records, he got a phone call from the agency of the Soviet government that managed (controlled) all the major Soviet artists. They had a live concert recording of Sviatoslav Richter they wanted to sell Columbia Records. Back then, because of the Cold War, Soviet artists didn’t make it over to the United States very often and there was a scarcity of recordings. Richter, if you don’t know, was one of the truly great pianists of the day, and of all-time.

Schuyler got the green light to buy the master tapes, for a significant sum of money. It was to be a great moment for Columbia Records and for Schuyler’s career.

The records were pressed, plans were made, and then a letter arrived from Richter himself begging Schuyler Chapin to destroy the recording. The letter was, in essence, smuggled in by another artist so the Soviets would not be alerted. Richter wrote that he was embarrassed by the performance and the recording was sold without his permission. Richter appealed to Schuyler’s honor to halt the project.

Schuyler then had to march himself into the office of Goddard Lieberson (father of composer Peter Lieberson), president of Columbia Records (also a composer by training) to tell him that the project had to be canceled, including the destruction of the recordings, and the writing off of the money paid to the Soviets. Schuyler offered to resign. This glorious story, as told to my by Schuyler, who happened to be one of the greatest raconteurs you could ever encounter, concluded with Lieberson telling him he would not accept his resignation, but to be sure never to let it happen again.

This early crucible in Schuyler Chapin’s career tells you much about the man. He would not let the great Sviatoslav Richter down and was prepared to lose his job over it.

He had a charm and grace about him that was from another place and time. The ability to put people at ease and the good musical skills to hit the right note and tone as a board member, a leader, and as a friend.

What was overlooked in the obituaries was his great leadership and commitment to arts education. He gave of his time and capital to help create The Center for Arts Education while bringing along the next generation of civic leaders committed to this cause, such as Laurie Tisch. He dreamed a dream along with many others of a public school system in New York City that would provide the power, beauty, and wonder of arts education to all its students. Where New York would be the arts capital and the arts education capital of the world.

Yes, he will be missed.

Thank you, Richard, for this detailed view of my Dad, with a new perspective. My brother Sam, the Massachusetts engineer, found this story, and has circulated it among family.