When I was about eleven years old, my family moved into a house on a Southern California palisade overlooking a country club that included a golf course, stables, a polo field, and a stadium. Sometimes I awoke to the sound of hoof beats—a horse pulling a sulky and its passenger around one of the rings below.

I don’t remember why my parents signed me up for riding lessons (although I can’t forget how the girls who owned, rode, and groomed their own mounts looked down on me). My strongest recollection is of a large, flea-bitten gray horse: Flying Cloud. He must have once been a competitor, because if I happened to ride him all by myself to the far part of the property, I could feel his energy change and see his ears prick up; he had spotted the fences set up at one end. Nothing I could do would stop him charging at one and then another and vaulting over them. Fortunately I knew enough to stand up a bit in the stirrups as he jumped.

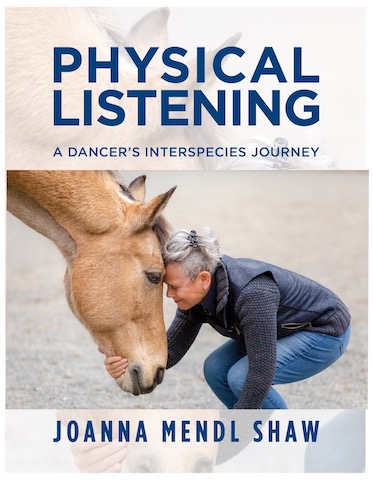

Why this lengthy introduction to writing about a book that, weeks ago, arrived via snail mail? The book in question is JoAnna Mendl Shaw’s Physical Listening: A Dancer’s Interspieces Journey (published by Arnica Press in 2021). Perhaps I delayed because long ago, I was advised to stay away from horses if I expected to become a dancer, and because the book’s author creates works for her Equus Projects that skillfully mingle costumed dancers with horses and riders. Perhaps, too, because I worked with Shaw decades ago, when I taught in a summer arts camp in Lenox, Massachusetts. Now we both have gray hair. And grown sons.

Shaw’s book is a hefty volume: 8 x 11 inches, 1 ½ inches thick, and stuffed with relevant images, both large and very small. In the Introduction, she advises us that “Perhaps you will read this book cover to cover, but feel free to cherry pick.” A wise instruction to someone entering fascinating, unfamiliar territory. Early on, its author introduces three terms that you may not have heard applied to the equine world: sponging, tracking, and mirroring (sponging is defined as “our multi-sensory absorbing of energy and action when moving with a ridden horse”).

One of the things that intrigues me about Physical Listening is that it takes me into a world I knew nothing about, as well as inviting me to adventure in a world I know better (mothering, dancing, choreographing). Shaw practices Parelli Natural Horsemanship, and, making use of its strategies, she has created pieces at stables in New York, New Jersey, Staten Island, Ohio, Montana, Sweden, and more. In the two weeks she spent in Thailand with a small group of people, her husband, and elephants, the humans also played a game involving trust and weight while walking downhill—paired and, between them, balancing a single long stick on their index fingers.

On that same page, Shaw muses about a Toronto study of babies, in which the infants early on seem able to perceive differences among images of various monkeys, but “they lose that ability” when they begin to understand language. . .when they learn the concept of ‘monkey’ and ‘animal.’” I mention this in order to point out that Shaw has a wide-ranging mind. “Embodiment” is for her a fact, a concept, and a way of experiencing the world.

And her world is rich and varied. She has worked with young adults with autism, noticed how she and her husband synchronize paddling their kayak, and made use of a life-sized inflatable elephant. In the course of teaching a Physical Listening and Performance workshop with horses and students at the University of Buffalo, Shaw initially thought that the students didn’t move their torsos fluidly. Discovering that her colleague’s dog had recently birthed a litter, she then taught an “embodied lesson,” giving each student a puppy to hold.

Shaw’s chapters have many sections and bold-faced, underlined divisions, such as In Practice with Horses, In Practice in the Dance Studio, The Score, Objectives, and Comments. The use of the word “Journey” in the book’s titles is apt. In the chapter “Dancing: Making a Visual Installation,” she recollects a doodling game she played with her father. Now within the small square that starts some of her book’s sections, she scribbles a big convoluted shape of curving lines, then subtly transforms it into a swarm of animals and faces.

The author also acknowledges and analyzes her mistakes, as well as the adventures and their results. Imagine this: “we would enter the paddock and begin moving through the space functioning as a unison herd of four. Our pathways would wind between sunbathing equines. In this herd formation we tried to avoid spatially crowding or pushing the animals.”

I don’t know how to categorize this book; it defies all attempts to do so. I was comforted by Shaw’s advice to “cherry pick,” but I also spread the volume on my lap and leafed through it—now pausing to think, now reading for minutes on end, and relishing this alluring, new-to-me world.

I must read and absorb this book! I too was at the summer arts camp with Shaw (and my studies with the author of this column at that camp led me to my current profession)! I was never a rider but my daughter was, and I would spend long, cold evenings in barns watching her do seemingly endless turns and maneuvers that made no sense to me. Now, as i spend most of my days thinking about embodied relationships between partners where one is severely movement-limited, I think I am starting to get the intricate sense of jointure of 2 individuals (human or animal). When we listen to one another’s cues (verbal, physical, visual), we can start to communicate differently. Going to buy the book now!

Judith, I would be delighted to have you read my book! When I first watched dressage riders, I felt like I was watching the grass grow.. Litlle did I know the depth of embodiment that skilled riding calls for.

I have consciously chosen not to ride, but rather work, dance and communicate with the horses from the ground. My dancers and I are all trained in Natural Horsemanship. The intersection of improvised interlude, directing the horse and responding to them an shaping into a legible choreographic language is a skill set we have been working on for years..

Much of traditional horsemanship is about dominating the animal. As dancers we a5re seeking Allyship. Different goals and a process that calls of constant physical listening as well as invention.

You can order the book for less than on Amazon on our website: http://www.equus-onsite.org

Beams,

JoAnna

Dear Deborah I’m so glad you wrote about this and posted it. I love horses and I love what she’s doing with horses. it’s amazing. And I can imagine you riding horses absolutely I’m sure you were very good. I used to ride as a child but haven’t for many many many years.

How beautiful! As an arts professional and a horse admirer (my sister Moira C. Harris was editor of Horse Illustrated magazine for more than 10 years), I find this subject fascinating. There’s so much we don’t know about how animals think, feel, and connect. Thank you for writing this book!

Adrienne Valencia

It has been a pleasure, reading through this book and getting a deeper understanding of JoAnna’s influences and accomplishments. When she worked with my undergraduate students, she translated her knowledge of natural horsemanship training into a studio choreographic practice that required the dancers to be as fully present in the moment as they had ever been, or as JoAnna put it—dancing in real time.

I know how well JoAnna writes from a few correspondences with her. I’m fascinated with her work with horses, as well as other things she does with dance.

Thanks, Deborah, for bringing your humanistic and generous consideration of this work. I will be making it a birthday gift for my niece who used to compete in hunter jumper events and whose feedback i hope to enlist at her wedding in less than a month. JoAnna, thanks and once again, congratulations on putting this into the world!