Here I go, repeating myself again: Dancers can’t not dance. Their bodies—their instruments—need to be kept in shape. Strategies emerge. Must they practice battements by lifting their legs between their refrigerator and their tv set? Even though the pandemic wanes, if they’re close to colleagues, do they need to be masked?

Sometimes, a simple iPhone on a stand documents their progress, but more often choreographers develop new skills and new approaches. Tamar Rogoff’s A Plague on All our Houses is a stunning example of how viewers hunched over their laptops can view a dance. (The work must have been a costly one to make, judging by the hefty list of donors at the end.)

No programs are available to leaf through, but Rogoff and her colleagues have found other ways to alert us to what we’re seeing and to introduce us to the diverse bunch of performers: Guanglei Hui, Michelle Mantione, Nick Owens, and Emily Pope. All races are represented, and Mantione wields a couple of light-weight metal crutches. We hear Rogoff’s voice, urging them at the outset to “explore the space.” The camera divides them into four sets of eyes. Are they watching us?

They introduce themselves. Owens, a bottle of Windex in hand, cleans his huge mirror, executes a back flip and a few arabesques before folding into the floor. Pope, first seen upside down as she washes her hair, smears suds on the wall she’s leaning against, and stretches a shapely leg. (That leg advances into a closeup, taking credit for its owner’s skill.) Hui uses his window sill as a barre, but also crouches within the window’s confined space, or stretches to fill it, using his torso as if it were made of an elastic substance. Mantione, free of her wheelchair, extends her crutch-bearing arms into the narrow space of her apartment and cuts high diagonals with them.

I notice that all four dance on clean, polished floors, that a blue truck once drives along an empoty street. I also hear a variety of recorded music as A Plague on All our Houses progresses. Gershwin playing a bit of his “Rhapsody in Blue,” Andrea Bocelli singing the Italian text of Mitchell Parish’s “Volare,” “Juliette’s Waltz” from Gounod’s Romeo et Juliette—these are only a few of the eleven pieces that accompany Rogoff’s work.

But we also hear the performers conversing with her, joking, laughing. Lacking printed programs for us, they take turns revealing themselves to us, but not in a “now me” way, since they occasionally “interrupt” one another and sneak into one another’s stories.

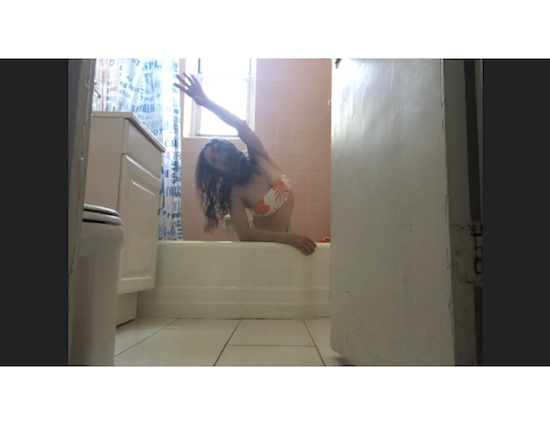

Pope shows a photo of herself—a little girl in her first solo on pointe, but her self-appointed task of removing and laying out skirt after skirt after skirt is intercut by the sight of Mantione half out of her bathtub, by two side-by-side images of Hui in his room, and by three neighboring shots of Owens. A blindfolded animal head (a camel?) takes note, and an aria ends with an invisible audience’s applause.

One interlude features the dancers working together but not together. For example, Owens reaches out a cupped hand, and Pope, in a separate frame, lets her cheek fall “into” it. In the end, however, the four fall in a heap, sweaty and disheveled. Note: this film must have been shot in the early hours of the morning. Almost no bystanders in the parks. No cars driving along the roads. We don’t see anyone bothering Owens as, masked, he exercises on a park bench. At home, unmasked, he and a partner laugh, do some pushups, his voice recalling college days.

This second set of solos reveals more about the dancers. Here’s Hui doing ballet exercises, while his baby daughter holds onto his barre’s lower rung and attempts pliés. On an empty street, Mantione lets us know that she is an arts administrator, while she gets out of her wheelchair, under it, stands, falls, sits, climbs stairs. We glimpse Brian, her partner. Pope, stretching and working out on a blue pad, tells us why she needed to be strong—teen-aged parents, an abusive caregiver, raising a child. “Dancers,” she says, “have been my family.” Imagine, again, being handed a program as you enter a theater. Instead we get a different kind of glimpse into the performers’s lives and careers.

Finally, we learn that it’s September 20, 2020, and the four arrive masked and gloved at LaMama’s empty New York theater. Each inhabits his or her own ring of meaningful cards on the floor. The lighting is dark, the music speedy (Is this “Earthly Heaven,” written and performed by Robert Een?), but the four move slowly within their circles.

Then what? Each stops, and together they bow. Not to the large invisible crew—to us.

Can you hear me applaud? I hope so. D

Dear Debra, once again, you write but you are not alone. I missed seeing Tamar’s film, now your writing brings the images to wash over my mind, I “join” you in the film, thank you. Have a good summer, Muna

Thanks so much for continuing your coverage, fitful though it must be, of pandemic dance on video. On writing about pandemic dance this past year-plus, I’ve found that while dance on video can create fascinating illusions (in Sofia Coppola’s NYCB film, when Maria Kowroski & Ask La Cour dance an excerpt from Liebeslieder on the marble First Ring esplanade, they seem to be floating magically above the floor), they are not the same as the illusions created by live dancers in front of us. And these are slowly returning, fortunately. Thanks for riding out the storm with us all. Oh–I should add that I’m not related to Tamar Rogoff, to my regret.

Lovely writing, thank you so much Deborah. I love especially “the baby daughter attempting barre.”