I’ve seen Mark Morris’s work for many years, starting in 1980. I remember him dancing half naked with a mane of black curls in his 1984 O Rangsayee. I interviewed him in Brussels, when he and his company had taken over the Théâtre de la Monnaie (1988 to 1991).A few years ago, I watched him rehearse his dancers in one of the nine studios in the Mark Morris Dance Group, built on a corner in Brooklyn. I saw some of his operas and his ballets, as well as his contemporary dance works. I missed his earlier work; he started choreographing at 14.

Still, in the midst of this pandemic, it was unnervingly impressive to watch him on my laptop’s screen and listen to him as a highly articulate, no-nonsense man with a mustache and a long, full gray beard. (It was also intriguing to see his superb male dancers (more hirsute onstage than usual.) And this was no home movie captured on someone’s iPhone. The credits that showed up on the screen revealed a host of professional video artists.

What I was viewing was the Mark Morris Dance Group’s, “Live from Brooklyn,” taped on May 7th. The four offerings were not full-company pieces. Laurel Lynch performed Three Preludes (1992) to music by George Gershwin; Brandon Randolph assailed Jealousy (1985) to “Jealous Pest,” HVW 60, Act 2 of George Frideric Handel’s opera Hercules; Karlie Budge, Lynch, Dallas McMurray, and Noah Vinson danced Tempus Perfectum (2021) to music from Johannes Brahms’s Sixteen Waltzes. Op. 69; and Mica Bernas, Christina Sahaida, Billy Smith, and Jammie Walker performed their Fugue (1987) to a composition by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

No matter how complex the steps that Morris choreographs,they amply display Morris’s musicality and musical knowledge as well as his dancers’ sensitivity and expertise.I’m aware of how skillfully he uses their bodies. That is, his movement phrases are not all about the legs or what big moves can be managed. In his works, a turn of the head may be as important as a leap, a sweep of the arms may give way to a small flicking of the fingers. The dancers give themselves to nuances as well as digging into huge, even sometimes clumsy moves. Their bodies—their very selves—sing.

Isaac Mizrahi has artfully costumed Lynch to unite her with the three Gershwin preludes that accompany her. Her form-fitting black tux is set off by white gloves and white gaiters over her black slippers, as well as by James F. Ingalls’s lighting, The choreography has a lazy ease about it, with suspended moments that seem like deep inhales. These contrast wonderfully with some extremely difficult moves—such as landing from a leap onto one leg and holding that position a second or so before moving on.

Like Lynch, Randolph wears a mask for his solo, but his is red to match the red trousers that constitute his costume. Philip Sandström’s lighting turns the cyclorama red too. The jealousy of the title can turn nasty, and Handel’s chorus of singers rub that in. We first see Randolph with his back turned to us, and as he moves closer, he droops at times, as if what he feels is weighing him down. No jumping for him, but his gaze is powerful, and he turns it in various directions, perhaps locating what he suspects. As he balances on one leg, he circles his wrists separately—almost as if reeling in dream prey.

For Morris’s premiere, Tempus Perfectum (accompanied by Colin Fowler on the piano), the four dancers are costumed in lightweight, loose-fitting suits in different colors: pale blue for Budge, red for Lynch, darker blue for Vinson, and green for McMurray, with black for the two men’s pants. Matching masks, of course. The performers behave as if there’s some kind of party going on offstage or they forgot something they need, so after dancing alone or beside someone else, they run offstage. The Brahms waltzes, diverse as they are, can soothe or incite these uneasy four. The dancers yield to the music expansively, tenderly; their arms form circles and embrace the air. But they also (especially McMurray) stumble occasionally, move clumsily side to side, their feet wide apart, and thrust their dancing onto the space. This time, the lighting is by Nick Kolin.

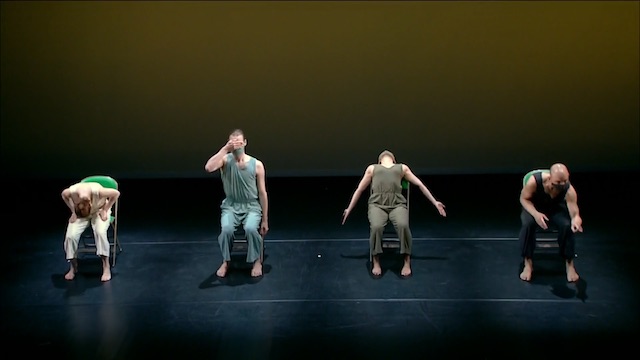

The onstage piano gets moved from place to place between each section. And Malcolm Bilson and Robert Levin sit side by side to play Mozart’s Fugue in C Minor, K. 401 for the last dance on the program. Bernas, Sahaida, Smith, and Walker clarify for Morris the fugal structure by sitting on green chairs in a downstage row. Lit by Sandström, they might almost be having a conversation, but not quite. They too are masked, and dressed in solid-color outfits: white, black, blue, or khaki.

For the most part, they face us. There are flashes of unison by two or more in their litany of stand, sit, gesture, paddle their feet in the air. Is it a true fugue? A partial one? Maybe, knowing Morris. But as Mozart’s music becomes more vivid, more urgent, the four are goaded into falling, rising, running offstage, and returning. The last image is of them back in their row and one of the women (Sahaida as I recall) standing and reaching out toward a seated compatriot. For the first time.

It has been a pleasure to watch Morris’ work all these years, and this program was especially sweet. I often see his modern dance ancestors reflected in his choreography, and this new quartet to Brahms really brought that forward. Duncan, Humphrey, and Weidman, as well as many more dance makers who have used these beautiful piano waltzes were all somehow on stage with this newest group. I know the pandemic has made my relationship to movement even more emotional than it has been in the past, but this livestream performance made my heart race.

Looks like Mark Morris inspired you to write a soaring lyrical review.