by Deborah Jowitt

Here’s what surprises me. I’m used to watching dance while sitting in a darkened theater surrounded by mostly silent people who’ve been given a fragile world to watch, examine, and think about. Every extraneous thought (well, almost every one), and every momentary discomfort gets pushed aside. These days, peering at dancing figures on a small screen, or past them to a grove of autumnal trees (wait, was that a squirrel?), is a different challenge. Family members walk by and ask questions. I pause the video. The telephone rings. I get up to peel a tangerine. Sigh.

Now I’ve been e-mailed a rich, if daunting array of hour-long videos that make up Yoshiko Chuma’s Love Story, the School of Hard Knocks, filmed at La MaMa on East 4th Street.There are twenty-four of them in all. Think about it. No don’t. I’m about to try writing about just two of them: #1 and #6, although I’ve been sent links to and photos from other videos in this inviting array.

These episodes don’t resemble most of the dance videos that have been flowing into my inbox. They’re artfully conceived and imaginatively filmed by Culturehub or the participants and edited by Chuma. The timing is also intriguing. A welter of activity may be followed by pause that gives you quite a while to scrutinize a person who seems to be looking out at you. Periodically, someone calls “blackout!” and you’re left to stare at the deliberately dark screen, wondering how many minutes will elapse before it lights up again.

I’ve been following Chuma’s career since at least 1981, when I saw her Champing at the Bit at St. Mark’s Church. (Was that the dance in which the performers built fragile “houses” by connecting a series of metal poles—houses open to the winds and prying eyes?) In her 1983 Five-Car Pileup, nine extremely individual performers did what I described as “rampaging wild-child dances.” Meanwhile, about sixty-two additional people in overcoats read newspapers, rolled them up, and used them as telescopes.

Chuma, who arrived in the U.S. from Japan in 1977, has presented pieces in cities all over the world. She founded her company, The School of Hard Knocks, in 1982, but also spent the years between 2000 and 2004 traveling between New York City and Ireland, where she choreographed for the Daghdha Dance Company. The pieces that make up Love Story are bewitching anthologies of her past; they ask questions about art and life and create new visions of the present. Perhaps you don’t need to know that when Nicky Paraiso speaks lovingly of “Harry,” he is remembering dancer Harry Whittaker Shepherd, who died during the AIDs epidemic. In watching episode #6, you might recognize a section of Chuma’s Suspicious Counterpoint, if you’d seen it in 1991. In it, no one gets to play the piano for long. Musician Mark Bennett begins by choosing a Chopin waltz, while Paraiso, plus others who are running around and falling, take turns shoving each other off the bench so that each individual can play at least a snatch of what he loves (some Gershwin is heard). Bennett doesn’t give up. Chuma ends the struggle by banging on the instrument herself.

Every now and then, there’s a long-distance, overhead shot that shows various dancers, musicians, stagehands at work amid the welter of stuff positioned in that black-box theater familiar to New Yorkers. Paraiso announces that, yes, we’re in LaMama, where no one has been since March 13th. There’s some fetching rule-breaking going on here. Near the beginning of #1, we see six people, marooned in their own habitats. They are Ryuji Yamaguchi, Kathryn [Ray], Tanin Torabi, Deniz Atli, Mizuho Kappa, plus violinist Ginger Dolden. But the five don’t relate to us in politely regulated ways; they all talk at the same time—loudly and volubly and in various languages.

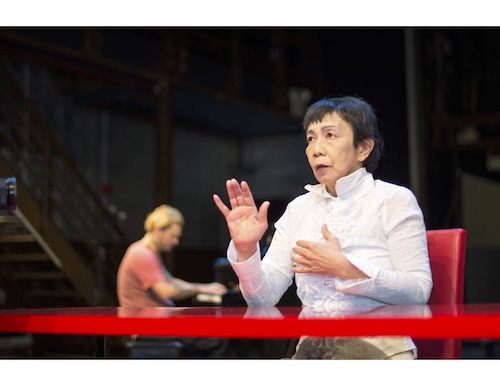

Red is the color that catches your eye: red-covered couch, red table, red chair. People sit to tell stories of difficult border crossings (Heather Litteer), to speak about an offer of marriage from a recently met Trumpist (Ryan Leach). Some performers think of sitting, but don’t stay. Occasionally, Yoshiko simply stares at us. But she dances too. When Robert Black plays his cello, and Dane Terry hits the piano keys, she fairly lashes herself around.

There’s plenty of intriguing dancing, some of it in collaged archival footage. But there’s also a lot of talking. Various performers sit in their homes and stare at the camera while an unseen voice recites the relevant bio. Guest artist Joan Finkelstein in Woodstock shares the screen with Chuma who’s elsewhere; they talk seriously of Yoshiko’s work past and present and what drives it. The topics raised in these encounters vary. For instance, Chuma and photographer Matthew Pokoik from Mt. Tremper Arts speak of his trip to Japan, the tea ceremony discussing the notion of “service” and how it may be interpreted.

Not all the intermittent events in #1 are happy ones. And the technology is not afraid to show us its seams. “Can you hear me?” asks Dolden. Could Jason Kao Hwang’s violin be a bit louder? Images get messed up deliberately. The final one— Black playing his cello —may begin hour #2. That’s what I’ve been told happens. So Ursula Eagly must have appeared at the end of #5, because it’s she who begins #6, even though, after we watch her sit and breathe, her image becomes a tiny postcard at the right edge of the screen. Equally small is the space inhabited by Saori Tsukada who prepares us for the six lessons we’re about to learn.

First comes a geography lesson (cue the map of Iraq, where the School of Hard Knocks has performed). Then a dance lesson, which doesn’t exactly happen, although a guest artist Valerie Scott is summoned, and we see her hands semi-artfully arranging small objects on a table. Then a lesson in running, which I can sort of make out in the 1×2 -inch picture at the screen’s right edge. (The runs are not very good, as we’ve been warned). Lesson #3 is my favorite, because it is, very briefly, devoted to Art History and Archaeology. In it, we learn of the layers that pile up over time, making civilizations vanish.

I begin to notice the shadowy figures who appear and disappear in the background—moving objects, covering the red sofa with green fabric, setting a microphone in place, etc. I see that whoever is holding the camera doesn’t hold still; he/she moves in, pulls back, tries out a new angle. Miriam Parker is dancing wonderfully; the movement slips and snakes around her body, shudders out of her shoulders . But we also see her seated and talking very clearly to someone (us?). “Can I interview you?” she asks. Chuma, wearing a gray silk shirt, slips in behind her and copies her equally eloquent gestures.

Many images and thoughts are stirred into the texture of installment #6. People, such as pianist Bennett, stare at us while a voice reads their resumés. When he sits at his instrument and plays softly, Chuma, Paraiso, Terry, and Mizuho Kappa group to listen to him. But they don’t lean in to watch (well, maybe Terry does a bit). Standing alone or paired, they stare in other directions.

Why does Paraiso decide to sing of a beautiful mermaid and then of angels, while Bennett not only plays for him but joins in the singing?

Watch the bustle of activity when Chuma carries in two door-sized pieces of plywood taped together. The group onstage starts rushing around it, ripping off the gaffer’s tape and hurling piles of it onto the floor. And what’s inside? Chuma lifts and holds up a life-sized, two-dimensional, seated-on-air image of a years-ago member of Hard Knocks: Mary Schultz. Glad she could make the show.

You keep feeling that reality, or the usual everyday events, have gone subtly awry, even as you remind yourself that many of the people you’re seeing and hearing— maybe once knew— have been associated with Yoshiko Chuma at one time or another. Remember singer Gayle Tufts? (I think she’s still big in Berlin). I spot cellist Robert Een, who collaborates with Meredith Monk.

Filmmaker Jacob Burkhardt, who also figured in Chuma’s career, is seen sitting in his home reminiscing. He’s the one who knows the origin of her company’s name “The School of Hard Knocks.” Holding up an LP record jacket of Pearl Bailey’s 1960 “Songs of the Bad Old Days,” he reads from its reverse side how that, for young artists, the “good old days” were their school of hard knocks. He recalls making short films with Chuma and composer Alvin Curran, aimed at the 1980 Venice Film Festival. You guessed it; we get to see some.

A man lies in front of a closed building, dreaming of the Grand Hotel des Bains, ocean waves, distant figures on a jetty (“Sogni del Casino”). We also watch Burkhardt’s face for a long time, wondering whether there is a next film. There is! Dark cars spin down dark streets where dark figures walk and headlights form dances, grow distant, zoom nearer. And amid all this, the voice of the late poet and dance writer Edwin Denby, reads a poem. Then, jolting along to feverish ,jazzed-up music, we’re taken to a gloomy early morning in New Jersey with the New York City skyline rising (“Martens Bar,” 1976).

Is there more? Yes! In 2007, Chuma won a Bessie Award honoring her sustained achievements in choreography, and for the ceremony, she created a montage of images from the School of Hard Knocks’ travels to cities all over the world. That’s what ends video #6. How young they all looked! How rambunctious! How adventurous! How greatly gifted!

Thank you Deborah: I see that your gift for putting us in the theater with you and making us watch the dance through your eyes transferred to watching it in front of a screen, minus peeling a tangerine.

Great description and response, Deborah, as always. Yoshiko’s unique, brilliant brain and artistic practice — and the panoply of extraordinary American and international artists she has interfaced with over the years — remind me why I’m in this dance business for life. Your reflective reaction tugs at my heart.

Thank you! This puts me in all those places past and present, right now. The best attribute of dance, through your writing.

On this election day, your writing here, which speaks of the current crisis but links us as you always seem to do, with the golden age of dance in America reminds us just how important and fragile dance is at this very moment.

I’m not familiar with Y. Chuma but totally intrigued and will look up her dance.

Your article was beautiful and magically written.

Thank you.