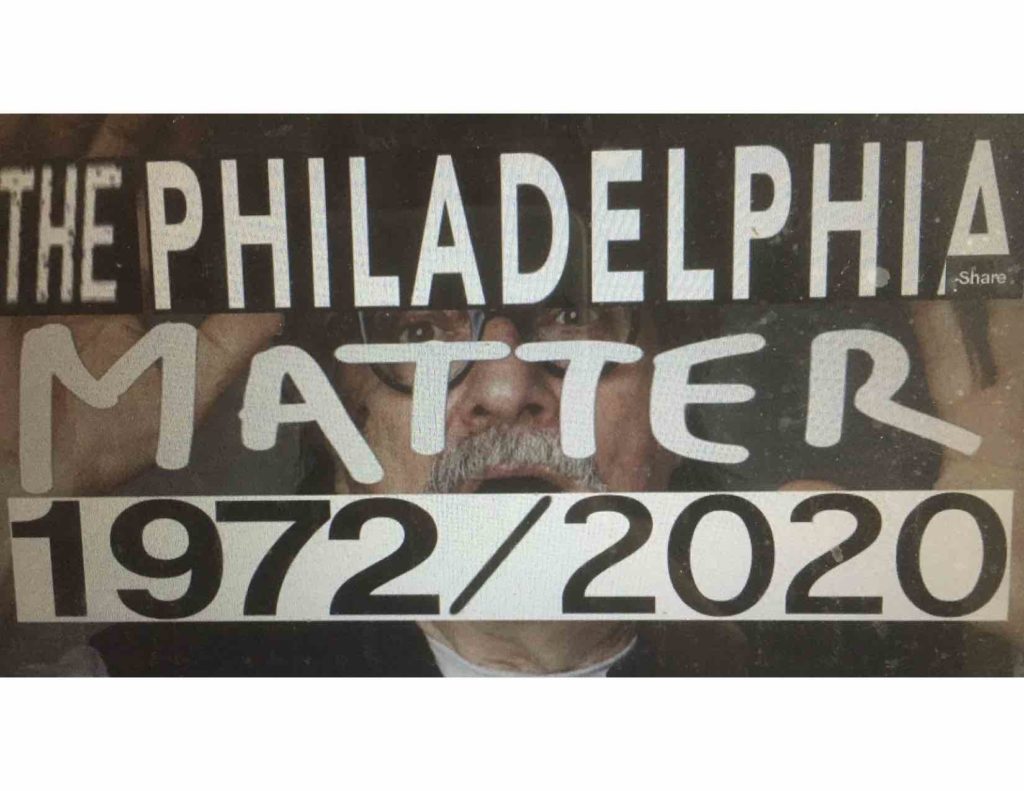

I sit at my laptop, looking out the window into a green world far from New York City. The screen announces “The Philadelphia Matter 1972/2020,” and glimpsed behind it is the large, alarmed face of its creator: choreographer David Gordon. The piece (no surprise) is propelled, guided, and shaped by words. Printed, hand written, large and small, the words reinforce what we also may hear spoken, and (again, no surprise), Postmodern poetry—written and uttered by Gordon and/or his wife, Valda Setterfield— repeats and enlarges upon itself.

The Philadelphia Matter, a curated work in Philadelphia’s 2020 Fringe Festival, takes its title from Gordon’s 1972 The Matter and from the twenty-six Philadadelphians who make up its cast and to whom he sent a video of him rehearsing his solo more than forty years ago. They’re to learn it. Given the visual style that shapes pandemic dance, the twenty-six dancers appear singly, three at a time, or more. Their individual cloistered images slide sideways onto and off of my screen, descend and ascend, appear and disappear, often garlanded with words.

In addition to showing material from The Matter, the 1979 Closeup, and the 1974 Chair, this virtual, incorporeal work delves into history. We’re told of the film Sunset Boulevard, which young David saw many times, or A Place in the Sun (cue the closeups of Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift). We also see snapshots of the song and dance master Fred Astaire and other nimble guys and learn of the MGM musicals to which one or another of Gordon’s four aunts schlepped him when he was a kid.

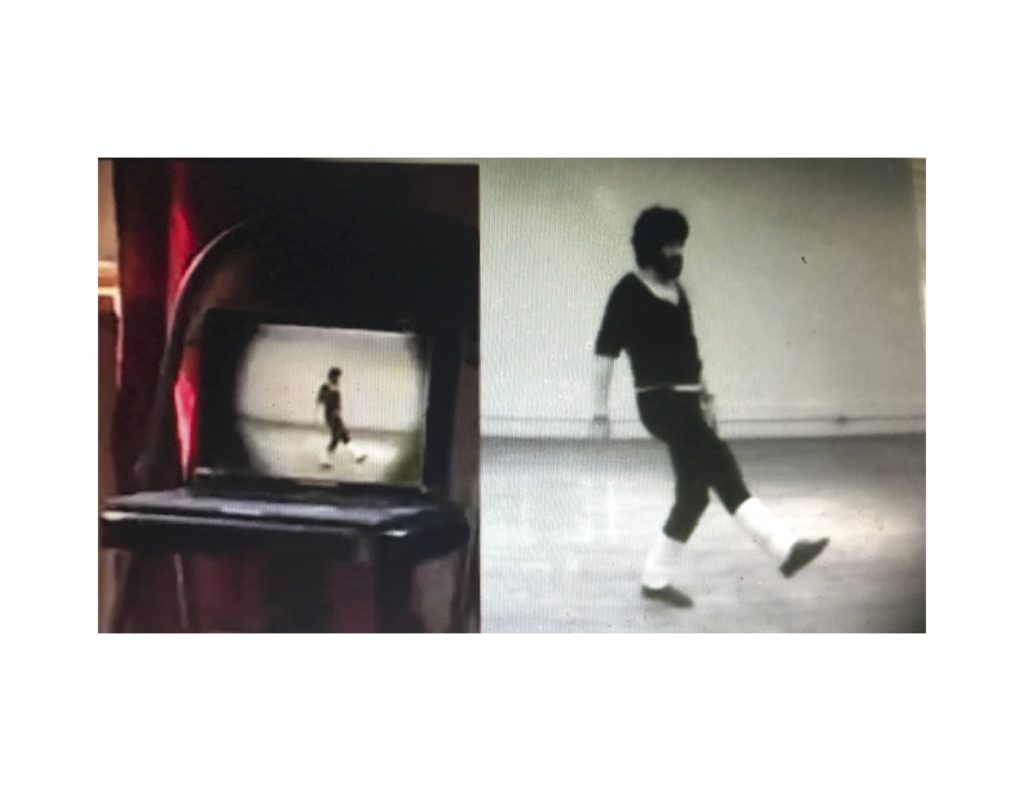

Maybe the movies he devoured back then helped propel him into talking and singing while he danced, and although there’s plenty of talking in The Philadelphia Matter, we never stop seeing dancing. The piece begins with a solitary woman whose space is the immense, empty Lincoln Center Plaza and grows from there. We hear voices and/or music almost all the time. And, if you look closely at the screen, you can see the Philadelphia dancers’ mouths moving when they perform The Matter. I’m guessing that they’re la-la-la-ing, just as bearded, shaggy-haired Gordon does in the blurry forty-year-old black-and-white rehearsal tape.

I’m far from the files that contain decades of my writings on dance, but watching Gordon takes me back to the 1970s. In the video of “Song and Dance” from The Matter, his dancing is as easy-going as his singing. His pedestrian moves—walking, turning, swinging his arms, dropping to the floor—look as if anyone could do them; nothing is pushed, extended, or shown off. At one point, he tells us that he and Valda sing and dance as if no one was watching, as if no one could see them.

Well, we do see them. We also learn quite a lot about Gordon as the words and dancing swirl and swarm around, and jazzy music plays. While finishing his college English major David joins a modern dance club. Choreographer James Waring tells him he could be a dancer. Doing that, he meets Valda Setterfield, who has left London for New York. She joins Merce Cunningham’s company. He asks her to marry him. She says yes. It’s 1961. Later they have a son: Ain.

Not all the dancers in this new/old work of his are young. We also see onetime performers in Gordon’s Pick Up Company— Karen Graham and Scott Cunningham, Graham and Wally Cardona. And we glimpse the younger Gordon and Setterfield in the 1979 Close Up, along with the today-era pairs in his cast (male-female, male-male, female-female). The title of the duet can be read in two ways: “closeup” as in a photograph and “close” pronounced “cloze,” as in closing a box. What is beautiful about the pairing is the task its participants have been given. One person, say, makes a circle of his/her arms, and the other one ducks carefully and rises into it. Maybe the first person lowers the circle so his/her partner can step out of it and appraise it. That’s their ongoing task: shaping embraces and supports for each other—always watching, always gentle, always tender. It could break your heart.

In another sequence Gordon and Setterfield mark their coming performance at the World Trade Center. It’s September 10, 2001. It’s raining. Men in slickers pass by. The performance is cancelled. Valda and David take the R train back to their Prince Street loft. The next morning, they look out their windows and see people running uptown along Broadway. It’s 9/11, and when they perform Close Up at the Joyce Theater, it becomes about loss.

The Philadelphia Matter is beautifully designed. (Here’s where I’d better credit Jorge Cousineau, Gordon’s expert video collaborator and editor.) One of the loveliest sequences happens in a green world, beginning with a tiny distant figure advancing toward the camera across a field. We hear birds. Images of the dancers appear in other green spaces as they perform “Song and Dance,” But we also see them in their apartments diligently recreating those carefully designed, noncommittal steps. At one point, the collisions and layerings of images become as distinctive as contemporary artworks.

Toward the end of the video, a new duet emerges out of necessity. In June of 1974, Setterfield, in the passenger seat of a car, was on her way to inspect a possible summer rental. The car was hit by a train and dragged into a telephone pole. Her head went partly through the windshield. Her face needed stitches. Gordon, on his way to Washington D.C., turned back. She, not remembering what happened, tells him that she’s had food it’d be a pity to waste. In her assigned locker he finds her bloody sweater and mashed cans of beans.

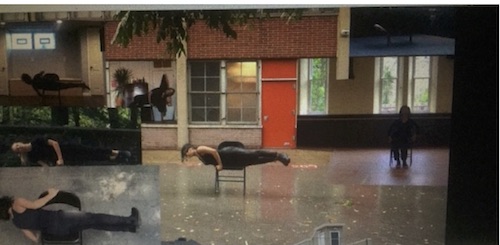

Gordon believes a new duet might help heal her. We hear both of them speaking. Lucinda Childs is one of those letting them use a studio. It has blue metal chairs, and slowly they begin to work on what will become Chair. Gordon piles coats beside his wife’s chair in case she topples and takes away the coats gradually, one by one. She starts remembering. What can the two of them not do on those clanking chairs. Eventually, they will tilt them, tip them over, step boldly on and off them, lie sideways on them, slide them down their bodies, fold them, trap themselves in them.

Images of the two performers proliferate. Black and white becomes color. “The Stars and Stripes Forever” pounds out its heroic measures, and finally, on a rainy street, one of the Philadelphia dancers sets a chair in place and begins Chair herself. Gradually, her collagues join, their disparate single images sliding up and down the screen, on and off it. A dog gets his own tiny window, which swiftly streaks away. The pavement turns into a roof.

In the end, the original dancer is alone. A tiny card in the lower left-hand corner says “The End,” and we hear a small crowd clapping and yelling their approval. I’ll add my cheers. Valda and David will have to imagine them.

Lovely, just lovely, the writing so vivid we don’t really need the screen captures. And Deborah has made me remember the first time I saw Gordon’s Pick-UP Company, in New York, in 1979, and how many years it took me to understand, at least in part, what he was doing, the sheer humanity of his enterprise.

I went to the talk=back this weekend with David, Jorge, Wally and several others involved in this…the pain of making this work (because it had to “stick” to the screen and couldn’t be re-improvised daily as it had been in real life) was a source of craziness in the collaboration process. And yet… so much good came out of it. There were no “rehearsals” but rather, continuing auditions, where the 26 performers would send in a self-tape and then be asked to enlarge it, put it in a different setting, repeat it in 1.5 minutes instead of 2 minutes. And wear black. Sounds SO hard! And yet… so much good really did come out of it.

Sterling. Endearing. Haunting. I believe David Gordon invented the folding chair, Valda his stalwart partner and a true star, a wife conjured up by by memories of MGM.

Gorgeous piece and gorgeous review Deborah. Just one thing. I think it was a box of mashed strawberries. Not beans. Whatever it was when David saw the bloody sweater he chose not to tell Valda.

Your writing brought me to the space again vividly. After watching the piece online I felt I was there with you.