People dancing in their rooms, their legs grazing furniture, their possessions on view for all to see. People dancing in meadows, in parks, on rooftops, through empty city streets, by the ocean. They are sometimes masked and almost always alone. Only longtime mates can sweat together. It’s 2020, and a pandemic has re-envisioned solitude.

What ties these dancers together is the choreography they’ve all learned from the directors of the company to which they belong. They’re in sync, or in counterpoint, and, however lonely they may be, they are, to those viewing them, confederates working together the way they always have. Their equality, of course, has to joust with their settings. Does that dancer really inhabit that cushy living room? This one must love to read; look at all those books! That one manages in close quarters. What a view from this one’s windows! Nice rug. Good hardwood floor. . . .

I’ve seen some online events during which I wonder whether an arabesque is going to knock over a blender, but that couldn’t really happen; space is something to which dancers are forever having to adjust. Another skill that some of them have developed is how to make a successful selfie. Some pretty skillful angles veer into Rooms2020 at times, although some may have been engineered by compliant unseen partners.

Among the at-home dances I’ve seen recently, one strikes me as truly suitable to performers who have to be isolated: Anna Sokolow’s 1955 Rooms, recreated for the pandemic as Rooms2020. In the original piece, even when there were quite a few dancers onstage, they were anchored to their straight-backed chairs, and the choreography conveyed powerful images of isolation in restricted spaces.

Jim May, a onetime Sokolow dancer and the founder and director of the Sokolow Theatre/Dance Ensemble, Samantha Géracht, its artistic director; and assistant artistic directors Eleanor Bunker and Lauren Naslund collaborated with eight dancers to produce the online production Rooms2020. Naslund directed and edited it.

We meet the performers lined up in two rows of four, all of them sitting on chairs as Kenyon Hopkins’s score kicks in. The jazz-influenced music is sometimes strident, sometime wailing, sometimes pushy, its New York sounds suggesting city streets, rough-edged encounters, and sudden silences. It evokes the town that Sokolow, the offspring of immigrant parents, explored in others of her works. I can believe that Hopkins composed the music alongside the choreography.

The creators of the film plumbed their knowledge of Sokolow’s Rooms for movements and gestures. Memories of the dance from years ago flash into my mind: Jeff Duncan and Ze’eva Cohen performing the piece’s solos, maybe Jack Moore too.

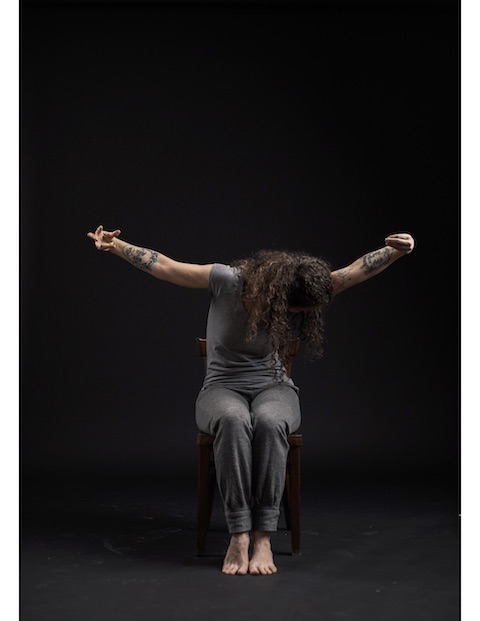

In sections with such titles as “Alone,” “Dream,” “Escape,” “Going,” “Panic” “Daydream,” “The End,” each character has his or her own idiosyncratic gestures, but they also share a common vocabulary. At times in the film, the dancers lean uncomfortably far back on their chairs, gazing upward, their feet relentlessly brushing the floor in front of them; walking and walking, they get nowhere, their desires not always in sync with what their legs are doing. Often they reach forward or upward with two straight arms. They lean over and press their heads against imagined (or in this case “real”) walls. They stand on their chairs. They lie on them, stretched out on their sides. Turning this way and that, a person hops on one leg, the other lifted behind, as if he’s stuck in that mode. They crumple or dive to the floor, curl up there, haul themselves erect again. Sometimes they seem to see themselves in a mirror; sometimes their eyes are fixed on whatever lies above them.

Samuel Humphreys, curled in and rocking on his rug, imagines being outside in a grassy wilderness. Three times in “Dream,” he leaves his comfortless home, but always returns. Erin Gottwald in “Escape” has no similar freedom. In a room with a sofa, she rests semi-suspended between two hard chairs. She pushes the skirt of her polka-dot dress up along her body as if it’s a skin she can’t get out of. Seated on her chair, she reaches up with both arms, but spreads her legs. Looking into her cell phone, she sees only herself.

Gottwald Brad Orego has no such softness. He begins and ends “Going” sitting on his hardwood floor, his head resting on his chair’s seat. His apartment in a hi-rise building surrounds him with glass windows. Surrounded by reflections, he gets jazzy in front of a mirror. In “Panic,” Luis Gabriel Zaragoza feels trapped in a room where his only companions are the many little pictures hanging on his walls. Twice he runs out into a bleak corridor. The music turns briefly stentorian as he presses his hands to his face. In the end, he’s curled up under a low table.

Photo: Samuel Waxman

Margherita Tisato’s tattoos are only partially concealed by the kimono sleeves of her costume for “The End.” Her hands are alive. Her fingers wriggle beside her face; they cover her face, clutch her throat. She looks up, reaches up, falls. In her final solitary moment, she’s standing on the chair.

The video’s creative team created more images of what it means to be alone together. In “Daydream,” Erika Langmeyer, Sierra Powell, and Ilana Ruth Cohen do their dreaming in their separate spaces, not always in perfect synchrony, and sometimes seen one at a time. In “Desire,” six chair-bound people repeat the motif of lying back, looking up, reaching out their arms, and working their feet rhythmically. But they also lie on the floor (briefly, some on top of others). Finally, they’re standing on their chairs, their heads hanging.

Watching this thoughtfully reconceived version of Rooms, you’re aware of the silences and the stillnesses that pit both the choreography and Hopkins’s emotionally and environmentally charged score. Is this what being alone for a long time feels like? What to do next? Why get out of bed? Are you going crazy? Are you alone by choice? If you died, who would bury your bones?

Instead, let us thank the powers that be for the sunshine and the moonlight and the grass that continues to grow. And thank the spirit of Anna Sokolow for showing us the darkness so fiercely.

Watching this reminded me of seeing it live in the 1980s with Stuart Smith, Jim May, Lorry May, Susan Thomasson, Dian Dong and so many beautiful other dancers —

I was fortunate to have seen Rooms in its premiere season while a student in New York more than a half century ago, its impact is still with me today

. . Anna Sokolow had that rare talent to search and find the essence of what she wanted to express and to choose those artists she knew would perform it with a deep honesty, revealing both themselves and the images and statements that Sokolow want to present,. In Rooms and many of her other pieces, I always had the feeling she was presenting people who showed their inner world thru movement, rather than dancers doing steps.

Never is her work pantomimic and yet we as audience are drawn into her work as we recognize ourselves and the situations of the characters of each work. She sought and found element of our inner world both dark and light, and had the artistry to bring it to us in the real meaning of dance theater .Seeing Rooms the first time opened up for me areas of movement theater that I always wanted to see but until then never experienced.

The always stirring and at times stunning connections between past and present make Deborah’s work relevant, personal and unique.

Wonderfully written Ms Jowitt. I had such

similar thoughts and feelings watching it

You spoke the truth of it just right.

I love this post for many of the reasons listed above, but also because I have never seen Sokolow’s work before, and to see it through such informed eyes, expressed with such loving eloquence makes it an intensely rich experience. And on a mundane note, when looking at dancers, dancing at home, I have had the same thoughts with which Deborah begins: I notice the books; I worry about what’s on kitchen counters; and sometimes I hold my breath when someone’s toddler tries to participate in the dance.