In today’s virtual world, I’m tempted by dance every day. On a hilltop miles away from the city I love, I can take an online ballet class, see parts of the many performances that had to be canceled because of Covid-19, or watch videos streaming from a dance company’s vault. Some times I’d have to make an appointment; sometimes I’d have to pay. (Meanwhile, excuse me a minute, I’ve been advised to plant a few hardy vegetables; the soil has already been dug up.)

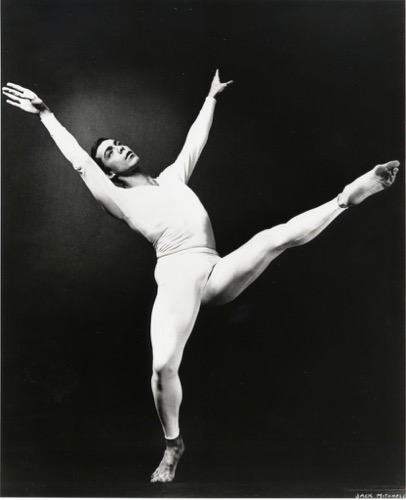

I’ve decided to look at Paul Taylor & Company — An Artist and his Work, a 1968 film directed by Ted Steeg (1930-2014) and offered online by Paul Taylor Dance Company. 1968! My choice was partly personal. The first dance review that I wrote appeared in the Village Voice in November of 1967. Quite critical of Paul Taylor’s new Agatha’s Tale, it was promptly and kindly criticized via snail mail by the choreographer. He may have remembered me from a few years earlier, when I had gone to his small, shabby studio, hoping to become a member of his company. Some audition! Just me and (unexpectedly) a teenager who’d been my student in a summer dance camp. As I recall, Paul said, “You’re lookin’ real good, but I need a little itty-bitty girl.”

Not long after that, I would come to know some of his dancers in other ways: Eileen Cropley, her friend (Tim?), and I were involved in a modest holiday concert that a friend of my mine was master-minding (and performing in) at the Manhattan School of Music. Senta Driver offered me sympathy and courage in the hospital where she happened to be taking care of newborns (part-time, I assumed). At the Martha Graham School, Bettie De Jong and I, being tall, often went across the floor together during morning class. Later she became Taylor’s invaluable rehearsal director.

Steeg, a noted documentary filmmaker, must have wanted his camera to dance too. He shot Paul Taylor & Company — An Artist and his Work in color and in all kinds of light. He often followed the dancers as if they were wild birds and might take off at any minute in unpredictable directions. The effect is almost dizzying. His camera swings around to catch something interesting, zooms into a close-up, cuts to another part of the room or another site, One minute he watches from the seats of an empty theater; the next minute he’s in the wings. Now he’s filming a rehearsal, now a performance of the same piece; now he’s crammed into a dressing room, listening to the dancers chat and watching them apply makeup. He moves in closely on two interlocked performers, until their skin, glistening with sweat, fills the screen He shoots over people’s shoulders during a small-scale fundraiser in the studio, with drinks and food afterward. He listens in while Taylor talks with his new young manager, Charles Reinhardt, and smiles inscrutably at what is being proposed. A guest star, the great French actor and mime Jean-Louis Barrault, attends a rehearsal, is treated attentively by the choreographer and shown his choreographic notes. Barrault approves of what he sees and kisses the beautiful dancer Carolyn Adams as he leaves.

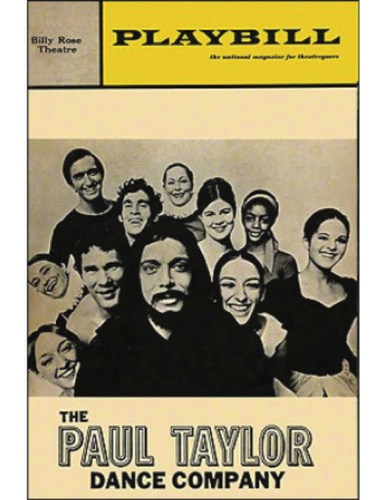

We hear Taylor’s voice a lot; it often rides over whatever we are viewing. Soft-spoken, clear, and polite, with traces of wit, he leads the viewer into his beliefs and processes. In many close-ups, he directs his gaze at us, his virtual audience. He needs a cigarette now and then. I imagine him hoping that this film will bring him the money he needs to present his work, and the film ends with the company taking over a Broadway theater (the Billy Rose I think), although it’s not made clear how many performances it can afford to give.

Steeg’s film shows us rehearsals, auditions, and classes, as well as performances. In the process, we understand why New York Times critic Clive Barnes, accosted by Al Maysles’ camera as he entered that Broadway theater, called the group “a lovely company.” Lovely it was indeed and full of very smart, devoted people (Adams, Cropley, De Jong, Driver, Janet Aaron, Cliff Keuter, Jane Kosminsky, John Nightingale, Molly Reinhardt, Daniel Wagoner, Daniel Williams, and Karla Wolfangle). For me, the best parts of the film are the rehearsals, during which Paul explains, comments on, and develops the material. The dancers try things, ask questions, propose solutions. They tell the camera that they learned a lot from Paul. One of them, Kosminsky, likes the fact that he sees them as individuals and builds on what he feels they can achieve: “He really gets your number down,” she says, and that often when performing a favorite work, “you feel it’s a dance you’ve been dancing all your life.”

The brief recurring dance passages are drawn from Agatha’s Tale, Aureole, Esplanade, Lento, Orbs, Piece Period, and Three Epitaphs (maybe more),but the sequences are interspersed, so it doesn’t make too much sense to try to identify them, even though you may note and remember the sort-of period costumes worn in the first of those dances and the all-white ones of the second. The long, practice skirt that De Jong once trails behind her may be part of Piece Period. (I’m 130 miles from my files or I could be more accurate).

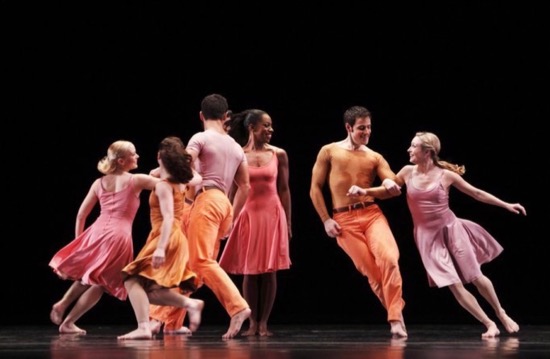

What matters to me in the clips is the freshness of the dancers. They rarely offer you a picture-perfect pose, unless the piece is a comic one. Their feet point but not stringently. They attack the steps as if these were a part of a fluent language in which they’re happy to be adept. You don’t admire how high they can kick, and they’re as likely to fall to the floor and roll as they are to skim along it or vault across it, their arms swinging. When the subject becomes dramatic, they can distort themselves into creatures you mightn’t want to meet on a dark night. Taylor may have learned about contractions of the body when he was a member of Martha Graham’s company, but he put them to new uses.

In the end, Taylor’s output consisted of more than a hundred dances. They contrast light with darkness, love with hate, virtuousness with animal urges, delight with despair. On such themes, he choreographed many variations. In theaters in cities around the world, audiences could gasp at the dancers in the 1975 Esplanade jumping up only to hurtle to the floor, or the women leaping into their partner’s arms from about a yard away. They could relish the simian antics of the tuxedo-clad men in Cloven Kingdom (1976); the jerky, predatory female coin-operated automaton of Big Bertha (1970), who destroyed a family visiting an amusement park; the tenderness of soldiers on shore leave bidding goodbye to their girlfriends in Sunset (1983); Sacre du Printemps (1980) retold as a kind of cartoon. And many many more. You could also relish the sterling dancers who worked with him over the latter part of his career. (At present, you can see them online in Matthew Diamond’s sterling 1998 documentary Dancemaker or purchase it on video or DVD).

This might be the moment to point out how varied, brilliant, and occasionally daring—was Taylor’s choice of the music that would inspire a dance or suit it to perfection. Also the moment to recollect the visual artists who were happy to collaborate with him on costumes or décor: Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Alex Katz, and Santo Loquasto among many greatly gifted others.

The good news, of course, is that the Paul Taylor Dance Company survived the death of its founder, as did the smaller ensemble Taylor 2 (this January two new dancers joined the first and one the second). Former company member Michael Novak assumed the role of the enterprise’s artistic director. In 2015, three years before his death, Taylor also established Paul Taylor American Modern Dance. Other companies performed his works on his programs, and other choreographers (Bryan Arias, Doug Elkins, Larry Keigwin, Doug Varone, and onetime Taylor dancer Lila York) created dances for the Taylor company.

This bad news just arrived from the company’s press agent, Lisa Labrado: “Due to the inability to rehearse and prepare the Company for performances in June, the TaylorNEXT Series at the Joyce has unfortunately been cancelled.” Don’t grouse about having to stand in line at the market only to find that there’s no more toilet paper. However, it’s perfectly all right to shed a few tears when summer comes without its expected offering of Paul Taylor’s works and his dancers to lift our hearts.

Very rich stuff!

I love this review, which bears all the hallmarks of your reviews of live performance, vivid description, deep contextual knowledge and over all really fine writing. You also make me want to see this film, so I’ll check out the Taylor Company website to see if they’re still streaming it.