James Klosty’s Merce Cunningham Redux is a big book in several ways (try lugging it to a sunny spot; it weighs about six pounds). Published late in 2019 by Brooklyn’s powerHouse Books and selling for $75, it first came into the world as Merce Cunningham in 1975 (Saturday Review Press) and reappeared in paperback with a new introduction in 1986 (Limelight Editions). In those earlier decades it measured 8 x 10 ½ by ½ inches and was 217 pages long. Merce Cunningham Redux measures 10 x 12½, is an inch thick, and contains 376 pages. In the earlier editions, essays short and long by such Cunningham colleagues as Carolyn Brown, John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Christian Wolff preceded a section of photographs by Klosty. In the new edition, the same writings, plus a new one, are interspersed between clusters of images relating to sixteen dances that Cunningham made between 1958 and 1972. I’m in love with it.

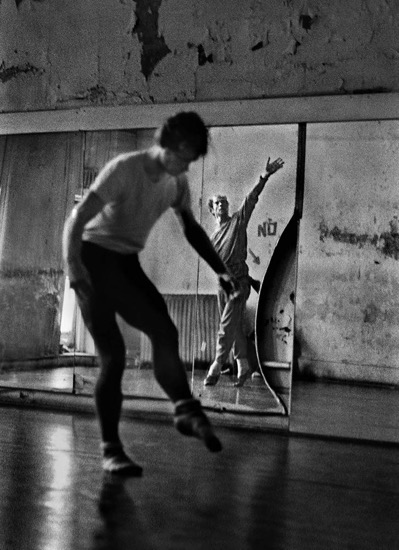

Most dance photographers—even those I’ve admired most, such as Barbara Morgan or Lois Greenfield—tend to freeze the subject at a peak moment. The swirl of a costume can hint at the motion that initiated it. In his introduction to the 1975 edition, Klosty wrote that dancing was “about qualities of movement. Not the shape of movement but the quality of movement. While photography is literally a timeless art——what’s left when time is taken away—dancing’s very being is time. The essence of its art is the linking of seconds into a language. . . .” His intent, he said back then, was not to create a dance book, that is not “to document or ‘illustrate’ Cunningham’s dances.”

Unlike many photographers of dance, Klosty didn’t invite dancers into a studio of his own or attend scheduled sessions that welcomed the press during dress rehearsals. In the 1970’s, he was close to a company member and had time on his hands. He travelled with the dancers, ate with them— perhaps foraging for mushrooms with John Cage. (on tour in Berkeley, California, preparing Spaghettini al pesto to feed an assembled party of forty, it took, according to Cage, five hours to wash and chop the basil).

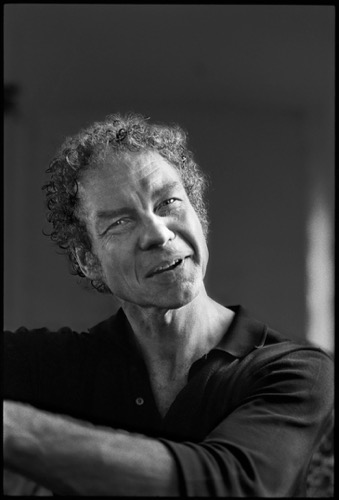

Klosty watched the dancers. They learned to ignore him much of the time. How else could he have gotten, for example, four indelible images of Brown and Cunningham in practice garb, ready to rehearse? She, gesturing, tells a story, he listens, gets increasingly interested; both of them explode into laughter; then, still laughing, they turn slightly away from each other, ready to move on. In another photo, Viola Farber, cutting Jasper Johns’ hair with the most gleeful of smiles, looks away from her task at someone we can’t see. His mouth curls up slightly; whatever she’s heard makes him grin too. Cunningham sits outdoors on a wooden step somewhere in Europe, amid the tangled wires, folding chairs, and heaped-up fabric to be used for an Event—one of those collages of passages from his works. Examining his hands, his feet slightly pigeon-toed, he is watched intently by one of two identically dressed little girls I take to be twins, while a third child looks mistrustfully at the camera.

Klosty’s collaboration with Yolanda Cuomo Design has resulted in an adventurous layout: double-page spreads, for instance, with no surrounding white space; images framed by a black line; two four-page fold-outs, one of which was the results of the same roll of film being accidentally run through the camera more than once. On some pages, several related pictures line up; a single one sprawls narrowly across two pages. Some images are grainy; some are blurred; some are dark. Valda Setterfield is almost silhouetted against windowed french doors, holding onto a doorknob as she does a barre, while her little son, Ain Gordon, barely visible, only slightly outlined by light, waits on a chair staring at Klosty and the camera that seems to have become part of his anatomy.

Whether the images in the book are ones of dances being performed or of offstage preparations, I can’t help feeling that they were influenced, however slightly, by Cunningham’s bold experiments in dancemaking. He saw the space of the stage as an open field, instead of hewing to its usual set-up of good places to be (downstage-right, upstage-left, etc.). He submitted his planning to chance procedures, such as tossing pennies onto a chart of possible moves. In keeping with this, Rauschenberg, touring with the company as its stage manager, often improvised a set out of materials found on the spot. Cunningham first saw Johns’s decor for Walkaround Time— which was related to Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass—at the dance’s premiere in Buffalo, and Johns saw the dance there for the first time. The dancers, as usual, had to be fearless, adept, and very game.

On tours that might be as strenuous as the ten-week one of Europe in 1972, the dancers became close—scrounging, foraging, and making do. Before Carolyn Brown had become a company member, her then-husband, composer Earle Brown, had paid for her lessons with a score commissioned by the company. No money changed hands. In the early days, before AGMA (American Guild of Musical Artists) became involved, Cunningham paid for food, gas, and motels, and the dancers got $25 per performance. The white Volkswagen mini-bus they often traveled in was bought in 1959 with some of the considerable money that John Cage had won on an Italian radio quiz show by identifying mushrooms correctly.

One of my favorite Klosty photos sets some MCDC people in a stony alleyway in 1970. Not, you might think, a restful place and possibly not very clean. But there, supine on the upper area lies lighting designer and video artist Charles Atlas, and there, their heads near his feet, sleep Gordon Mumma and Mimi Johnson, her head on his chest. Carolyn Brown, however, is awake. Sitting in the lower space, leaning back against the wall—her book laid aside, her hands folded in her lap, her legs turned out and neatly spread—she gazes slightly upward. We will never know what she sees or what she thinks, but I imagine she’s doing both.

Merce Cunningham Redux comes out ten years after Cunningham’s death in 2009 and eight years after his company’s two-year Legacy Tour ended on December 31st 2011— the last of six stupendous, three-ring performances in New York City’s Park Avenue Armory. So Klosty’s creation is not a “dance book?” No, it’s a book that reveals dancing as an art form, a practice, and a way of life that involves hardship but is often filled with joy.

Here is one of my favorite Cunningham quotes: “You have to love dancing to stick to it. It gives you nothing back, no manuscripts to store away, no paintings to show on walls and maybe hang in museums, no poems to be printed and sold, nothing but that single fleeting moment when you feel alive.”

I was at Brandeis in the 1960s with Klosty and we acted together in many plays. I was fascinated to hear of his relationship and then how it led him to a living partnership—as you say, “ a way of life,” with Merce and his company. No one else could have taken these pictures! The book price was a sticking point for me, but after reading your review, I have to have it.

what a comprehensive review of this Merce book.

I’ve always been curious about the photography of Cunningham, as well as the writing. So I appreciate your thorough review of this heavy book.

It’s a magnificent book, and your piece about it is no less masterful. I so appreciate the way your commentary on this book is consistent with the way you might write about a dance; in both cases helping us to see the work in question more fully.