Merce Cunningham (1919-2009) didn’t want to tell spectators how to look at his dances or how to interpret them. To him, the stage space was an open field, often busy with activity; we could look at whatever drew our gaze. His dances didn’t “go” with the music the way those of other choreographers did. Whether the scores that accompanied them were by his life partner John Cage or by other contemporary composers, the music wended its own way in the designated amount of time, and the dancers rehearsed to counts governed by a stopwatch. The sets—maybe by Robert Rauschenberg, who also served as stage manager on the Merce Cunningham Company’s grueling tours in the 1960s (partly via a Volkswagen minibus), maybe by other visual artists of note—formed another independent strand. So did the lighting and the costumes. How these separate entities came together in performance inevitably surprised the performers as well as the audiences. And since Cunningham used various chance procedures in making his dances (say, throwing dice onto charts), he may have been amazed at the outcome himself.

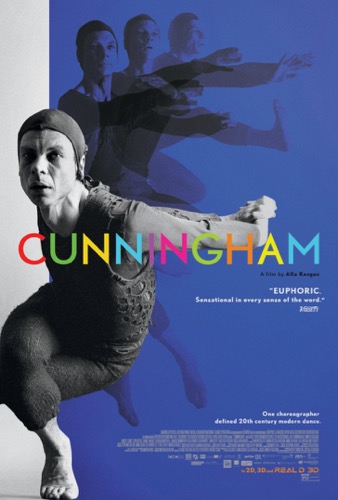

In 1977, when his work was the subject of a video in the Dance in America series produced and directed by Merrill Brockway, the choreographer studied the ways in which shots of his works could counteract the screen’s two-dimensionality. Cunningham, Magnolia Pictures’ new 93-minute film by Alla Kovgan (made in Germany, France, and the United States) not only shoots its dancers in three dimensions, but collages historic, two dimensional black-and-white images in smaller sizes on the screen, often overlaid with print from newspapers or Cunningham’s book, Changes: Notes on Choreography. This practice allows us to choose (or stumble upon) those visions most meaningful to us, or to accept multiplicity and not worry about what we didn’t see.

Merce would surely have appreciated Kovgan’s effort not to direct our focus too stringently or dictate meanings to us about the excerpts from fourteen dances she has chosen to show. In his 1955 essay, “The Impermanent Art,” he wrote:

“So if you really dance—your body, that is, and not your mind’s enforcement—the manifestations of the spirit through your torso and your limbs will inevitably take on the shape of life. We give ourselves away at every moment. We do not, therefore, have to try to do it.”

The film’s sequences in color are ravishing and unexpected. Various of the fourteen dancers appear in the former Cunningham studio, on the Westbeth roof, in a forest, on a pink floor in a garden, in a corridor whose ornate wooden grills slide back and forth, in a glassed-in bridge over the West Side Highway, on two stages set up in the vast courtyard of a European palace, in a dark space under a single light bulb, in a brightly lit tunnel, seen intermittently through the openings in a wall. And more. Kovgan and her Directors of Choreography, Robert Swinston and Jennifer Goggans, must have wanted to convey the company’s travels, but, more importantly, to suggest the ways in which our vision of a work could change. Kovgan has written that she wanted to “re-imagine each as an ‘event’” like those assemblages he staged in specific locations (often public spaces).

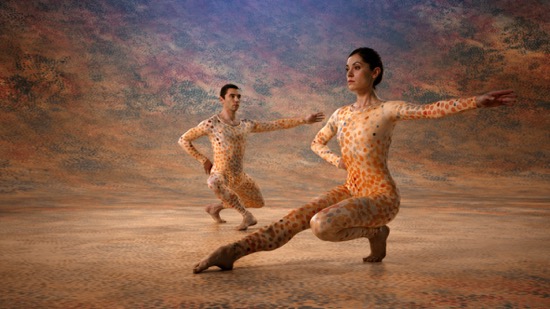

We see Brandon Collwes and Jennifer Goggans in the almost violent duet from the 1968 Rainforest (originally performed by Merce and Carolyn Brown), the dancers lashing amid Andy Warhol’s helium-filled mylar pillows). We see excerpts from Summerspace (1958), in which the performers are not only working in front of the pointillistic Rauschenberg backdrop that mimics their speckled costumes, but on a digitally recreated floor cloth. Between the re-imagined pieces and the historic footage, we get glimpses of twenty-five works.

The single camera may occasionally watch the dancers from an airplane or pan artfully, as in a section of Suite for Two. We first see the man and his partner in the distance (Daniel Madoff and Jamie Scott)—two small figures in what might be the allée of an unseen chateau. As they dance together in quiet intimacy, the camera glides slowly away from them over a bank and, travels backward along a waterway reflecting the overhead greenery, never altering its perspective. Then it advances toward the pair again, as if we’re on a boat retracing its path.

© Mko Malkshasyan. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

The glasses handed out before we take our seats aren’t the old-time red eye/green eye sort; they seem like regular glasses until the film begins and we see how fascinatingly Kovgan and her crew emphasized the three-dimensional sequences. Dancers entering the frame in the foreground seem to materialize out of nowhere, their largeness emphasized. Often we’re given markers to enhance our awareness. For instance, when the dancers are roistering in the woods, the camera has to pass a huge tree trunk that sits between them and us (it’s almost shocking). We see the distances between people and objects instead of simply accepting the fact that they must be operating in different planes. (We’ve been going to movies for so long that our eyes have been trained how to watch a flat screen and deduce depth.)

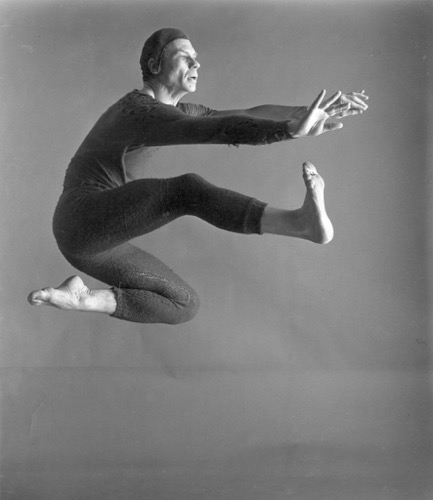

The film contains a wealth of old footage. Cunningham skidding along on his knees (omigod!). Cunningham dancing at the peak of his powers. We get to watch and listen to him and some of the great dancers in his original company: Carolyn Brown, Barbara Lloyd Dilly, Viola Farber, Valda Setterfield, Sandra Neels, Gus Solomons jr. There they are in their youthful black-and-white splendor in clips from the 1967 documentary, 498 Third Avenue. The paint is crumbling off the studio’s walls, and the heat doesn’t always work, but we can revel in, say, Cunningham hovering over Neels and Solomons, directing them as they fit together in ways that could seem deliberately erotic in the hands of another choreographer (a fact that Neels later acknowledges in a tired aside to the camera).

Rich though Kovgan’s film is and as splendidly assembled, there’s one thing it doesn’t reveal. In Carolyn Brown’s 2007 book, Chance and Circumstance: Twenty Years with Cage and Cunningham, there are photos that show the dancers’ fatigue, the ways they found to rest in uncomfortable places, but also their humor and the fun they managed to have. Their joy and their intelligence fueled their boss’s creativity, whether he told them that or not.

I’d like to honor the former Cunningham dancers who appeared in the film’s reconstructions: Ashley Chen, Brandon Collwes, Dylan Crossman, Julie Cunningham, Jennifer Goggans, Lindsey Jones, Cori Kresge, Daniel Madoff, Rashaun Mitchell, Marcie Munnerlyn, Silas Riener, Glen Rumsey, Jamie Scott, and Melissa Toogood. My hat’s off to all of them.

I mostly loved this film and wish I could have seen it more than once, since I missed quite a bit with one viewing, as Deborah’s post reveals. I do think all dance films should be shown in 3D, which I’ve said repeatedly elsewhere, inspired as well by the 3D film of Pina Bausch that appeared several years ago. I would have liked to have known in which European cities the performances we saw in the movie were filmed, which sites. And that Todd Bolender’s name had been mentioned by someone, (Carolyn Brown does mention this in her wonderful memoir), because it was he who invited the company to participate in the Cologne summer festival on that 1964 tour. Picky of me? Probably. But since Bolender was directing the Cologne Opera Ballet at that point, this seems to me to be an indication of the respect that at least some ballet people had for Merce’s work.

Thanks as usual for the eloquence of your writing and the clarity of your insights.