When I watch a dance that I’ve also seen a few years earlier, I perceive it differently. Maybe I hear it differently too. Has it changed? Maybe. Have I changed? Of course. So has the world. I’ve viewed and written about all but one of the works dating from 2011, 2017, and 2018 that members of A.I.M (Abraham in Motion) performed this past week at Jacob’s Pillow. Some new dancers have taken on the roles designed by the company’s Artistic Director, Kyle Abraham, and by guest choreographer Andrea Miller, director of Gallim, and things catch my attention that evaded it before.

(And here’s another question: do I only remember what I wrote about and forget what I didn’t mention earlier?)

At Jacob’s Pillow, where A.I.M has appeared four times, why would I not have paid more attention to the vivid, changeable lighting designed by Dan Scully or Nicole Pearce? Scully’s lighting for Drive (2017) begins with a row of red footlights at the back of the stage and above them four sets of eight lamps arranged like windows. Smoke pours onto the stage. And that’s just the beginning. Certain aspects of Abraham’s choreography seem not to have imprinted themselves on my mind. For instance, the dancers’ arms are often very busy and wonderfully fluid. In The Quiet Dance (2011), their fleeting gestures may suggest pulling fabric around themselves or slipping a scarf about their necks; these aren’t pantomimic, simply components of a muscular lyricism.

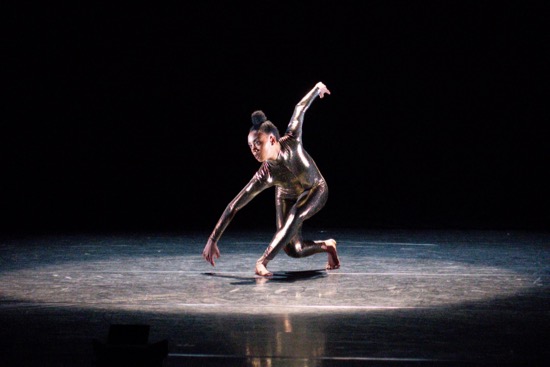

Abraham’s style draws on ballet, modern dance, hip-hop, various vernacular forms, but, molded by his own unique sensibility, rarely do these sneak into the foreground. You feel the movements—sensuous, weighty—rippling out from deep in the dancers’ bodies. Sudden steps flash out and subside. You don’t think, “oh, a leap;” instead you watch an eruption. In the solo Show Pony (2018), set to Jlin’s “Hatshepsut,” terrific Marcella Lewis (who alternates in the role with the equally terrific Tamisha Guy), wears a skin-tight, shiny gold unitard. Her legs may flash into the air, catching the light, but you see every bone of her mobile spine, a kind of generator pressing her into motion, seeking crevices of air.

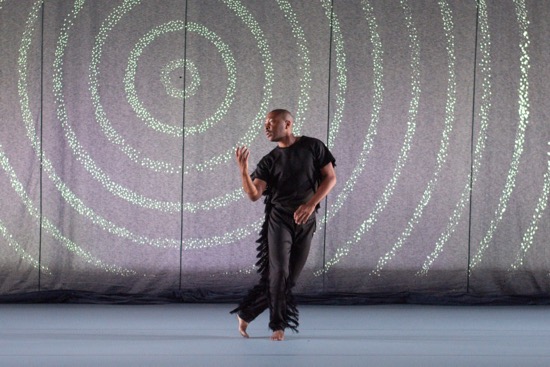

That’s not the only solo on the program. Abraham reprises his 2018 INDY, and I don’t know which of many meanings of that word he was choosing. He’s wearing a black sleeveless top and matching pants, both of them fringed like buckskins of the old West, but infinitely more elegant. What I hadn’t remembered is that he almost never stops walking—crossing the stage on diagonals or straight lines toward and away from us. Those walks are revelatory. He could be revisiting his life as if it were a condensed travelogue. Sometimes he strides with a kind of leisurely boys-in-the-hood confidence; occasionally, he affects (or perhaps signals) clichés of femininity: tiny steps, a coy glance, a kissy mouth, a finger smoothing his eyebrow. Jerome Begin’s potent score mingles piano notes with occasional human voices, thunder, a sudden squawk.

Abraham never lets us forget that things are happening to him in Pearce’s shifting paths and beams of light. He slows down, speeds up. Pauses. He may talk silently, smile, laugh; he may travel upstage, where a mysterious light glows high up, and the black curtains open to reveal grayness. Toward the end, he removes and carefully folds his shirt and pants. And then he’s cold, but not in response to the weather. He’s jerking, curling his body over, his movements halting. He puts the shirt back on, and soon, after walking away from us, bends over, his back to us, subtly convulsing. Maybe sobbing. But when he comes toward again, he’s smiling, even though one of his hands can’t stop shaking. The music fades. The lights dim to black.

You can marvel at how Keerati Jinakunwiphat, Catherine Ellis Kirk, and Lewis move in perfect synchrony during the first two sections 2018 state, by guest choreographer Andrea Miller. Attended by Reggie Wilkins’s score, whose first sounds are crowd noises and voices rising above them, the three women—bent over, their backs to us—tread the floor, silhouetted by Pearce’s lighting. Gradually they turn to face us, take little side steps, little kicks, plant their feet in a wide stance, move their arms, sway their hips. Their gaze is often upward.

In the second section, they begin sitting on the floor, facing on a diagonal, arched back until their heads touch the floor. Imagine an exercise class in hell. At one point, facing the floor, they balance on their knees and elbows, their hands pressed against their faces. Oddly, I can imagine the dance performed as a solo; Some of these moves suggest ones you’d make when alone. Yet, although the three women dance in unison until the last section, they come across as individuals. In that final part, Ellis Kirk dances with her own shadow, projected on the cyclorama. Still, before returning to their initial treading, the three cluster holding hands and, heads together, lift their wreathed arms overhead and lower them into a group embrace.

Abraham’s The Quiet Dance, mentioned earlier, is quiet both aurally and visually. It’s performed to a recording of Bill Evans playing a piano rendition of Leonard Bernstein’s “Some Other Time” from On The Town. Ellis Kirk works alone on one side of the stage for much of its duration, while various of the others—Baker, Guy, Jinakunwiphat, and Claude “CJ” Johnson—come and go on the opposite side. In this work, dancers are often in unison, but small breaks occur. For instance, four paired dancers are packed close together, facing us, but for a short time, the two in back turn to dance face to face. Later, two stop and hug.

Toward the end, you feel the tenderness among these people, even though they rarely touch, as they fit themselves into patterns. Ellis Kirk echoes elements of these only briefly before returning to her own musing. She’s the only person onstage when the lights go out, walking away from us. Perhaps she dreamed the others up.

Dan Scully’s lighting for Abraham’s 2017 Drive (also mentioned earlier) turns the stage into a dangerous place. One in flames. You can’t always see the opening in the rear curtains through the smoke. Sometimes the performers don’t just exit back there; they seem to get swallowed up. The music by Theo Parrish and Mobb Deep plus additional sounds by Sam Crawford add to the atmosphere of danger. From deep in it, voices occasionally whisper or cry out (did I hear “Try yourself try”).

Now that Donovan Reed and Jada Jenai Williams have joined those already mentioned, there are eight people—all splendid performers. In this dangerous climate, they try to be orderly, do what they usually do—that is, dance. But you also see them clump together. You spot two of them sparring, one of them helping another. Does the title Drive mean get the hell out of here? Could be. But, strangely, near the end, four white neon tubes, suspended vertically, mitigate the disastrous lighting. Is that a hopeful sign? Or just a wish?

Abraham—born in Pittsburgh, a student of art and the cello as well as of dance, the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship and other awards—has built a rich career of world-wide touring for A.I.M. and ventures for himself as a choreographer (the Alvin Ailey American Dance Company has an Abraham; so does the New York City Ballet). Some members of the Jacob’s Pillow audience were heard nervously asking one another, “What do you think it means?” But they stood up and cheered, so I’ll bet that, deep down, they knew the answer.

It’s wonderful to read about dance through your witnessing and audience experience. I very rarely get to a performance and on first read of your words I often think, ‘it’s like being there!’ But no, actually on further reflection it’s actually much different. Reading your writing is a creative enjoyment in itself. I appreciate the rolling of your words and the language you move around and wrestle with to give us a sense of what you saw, felt, remembered, thought, heard, noticed…..

Agreed – seeing a work several times, especially with time in between, helps the viewer as well as the choreographer! I’m remembering Abraham’s very obvious statements about sexuality in Pookie Jenkins with that huge white skirt, But the walks around the stage you discuss seem to change his gender in a more even way.

I also loved seeing his wonderful dancers doing another choreographer’s work (Andrea Miller’s) .

Deborah – you keep me aware of what continues to evolve in a world I have long since lost, unable to keep up with the witnessing required. Hope you are well. So love your writing and the way you allow your reader into the experience.