Compagnie CNDC-Angers/Robert Swinston visits Jacob’s Pillow

Once upon a time, Merce Cunningham wrote about the dancing that mattered to him: “[y]ou do not separate the human being from the actions he does, or the actions that surround him, but you can see what it is like to break those actions up in different ways, to allow the passion, and it is passion, to appear for each person in his own way.”

I didn’t think of this at Jacob’s Pillow while watching Carlo Schiavo of Compagnie CNDC-Angers/Robert Swinston as he, alone onstage, began Cunningham’s Suite for Five (1953-1958). But I did take in Schiavo’s alertness to the space around him and the ways in which he could move from slowness into a sudden burst of speed into a remarkably steady balance on one leg. I could clearly see what he was doing, but I wasn’t moved to ponder why he was doing it. That is, I saw passion, but understood that he was not responding to a crisis in his onstage life, nor was he was dancing to show off his fine technique.

Cunningham, abetted by his colleague and partner, John Cage, employed a variety of compositional procedures in order to knock his choreography into patterns as unpredictable as those we experience daily. His book Changes: Notes on Choreography is full of risky strategies, such as throwing dice or coins onto a chart of possible moves. The three Cunningham pieces that CNDC-Angers brought from France to Jacob’s Pillow this summer— Suite for Five, Inlets 2 (1983), and How to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run (1965)—require no more than eight dancers, and even so, intense awareness of one another is a given. Especially since the scores by Cage that accompany them don’t provide a beat.

Swinston has been involved with Cunningham’s work, ever since (or even before) he joined the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in 1980, and he has conveyed to the French company the rigor and the daring that the pieces demand. The dancers meet the challenge superbly. History may have buoyed them up (in 1971, Swinston was a scholarship student at Jacob’s Pillow). Director Pamela Tatge’s introduction and a series of film clips establish Cunningham’s company there: his Banjo in 1953, his Sounddance in 1975 and many pieces between and after these. In 2009, when he was unable to travel, Pillow performances were live-streamed to him; he died not long afterward.

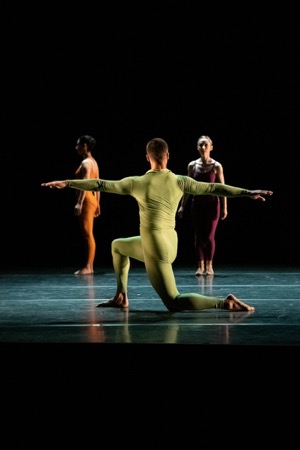

None of these three Cunningham works can be easy to perform. In Suite for Five’s short sections, separated by blackouts, you may see any one of the dancers (Anna Chirescu, Gianni Joseph, Catarina Pernão, Claire Seigle-Goujon, and Schiavo) slowly rotate on one leg, holding the other high, like a weathervane in a gentle wind. It’s especially memorable in a solo by Pernão. All the dancers in Suite for Five are given to bounding into the air. Also to lunging deeply. And, as in all the works on the program, one person may fall into unison with another as if by accident. As the dance progresses, you may focus, say, on the deliberate slide of one person’s foot against the floor. Or be startled by the moment in which Joseph leans on a slant braced by his grip on Seigle-Goujon and Chirescu, who hold each other’s hands. At another moment, backing up on his knees, Joseph gives the floor on either side of him a little slap with his braced hands.

The dancers are not alone in drawing our eyes. In front of the stage, on a level with the first row of audience members, Adam Tendler hovers over a piano, not only striking its keys to play Cage’s Music for Piano 4-19, but reaching into it to pluck or strike its strings.

Who, by the way, designed the costumes of Suite for Five (and doubtless dyed the originals)? Robert Rauschenberg.

Cunningham choreographed Inlets in 1977 and Inlets 2 in 1983. His company first performed the latter in France. It has seven dancers instead of the original six, but also, as the program explains, “The same gamut of sixty-four movements was subjected again to other chance operations.” In other words, the order of them changed.

The title of the work brings to mind the fact that Cunningham grew up Centralia, Washington. The Pacific Ocean was about thirty miles to the west, and from Seattle the inlets of Puget Sound reached southward like fingers. Cage’s score, Inlets (1977) sounds like water. Is water. Near the piano, sits a table holding two full pitchers, several huge conch shells, and a variety of smaller ones. Tendler, Laura Kuhn (executive director of the John Cage Trust), and, at the performance I saw, Swinston, pour water into the shells and tilt or shake them close to microphones. You hear lapping, sloshing, bubbling—sometimes in deep tones, sometimes in shallower ones. Once, at the end, Tendler blows a piercing note on a small shell.

The women (those named plus Flora Rogeboz) wear long-sleeved dresses with short swirling skirts in shades of blue and bronze and gray. The men (plus Pierre Guilbault) wear tights and leotards in similar colors. Mark Lancaster, who designed the beautiful lighting as well as the costumes, set them against a deep blue sky or a violet one. I think of sea birds, as well as tides, as I watch the dancers flock and separate, move swiftly or stay motionless. When they stroke one hand down their other arm, I think of birds. When they jump, they fly. Occasionally two or more move in unison, but that quickly dissolves. And, like birds, they don’t touch one another.

How to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run is as sporty as its title. The eight performers (those mentioned plus Matthieu Chayrigues) wear black tights, bright-colored shirts, and ankle warmers. Beverly Emmons’s lighting is bright, and the wooden back wall of the stage is exposed. Kuhn and Tendler sit onstage left at a small table, with access to a bottle of champagne, two glasses, microphones, scripts, and timers. Throughout the piece, they read various of the short witty stories from Cage’s 1958 lecture “Indeterminacy” (included in his 1961 book Silence). Each story must be read in one minute; this means that the reader may sometimes have to speak slowly and pause often, and at other times to fairly gabble. I like the way your attention veers between the “players” and the unstopping (and unrelated) talk of the “referees,” although this time, I’m not sure why, Kuhn and Tendler spoke simultaneously more often than I remember from previous performances. That was disappointing; the tales are too delicious to miss.

This work is like a game whose rules are invisible, distorted or non-existent. For instance, Joseph (as I recall) travels sideways, packed between two women, and, as they go, turns now one, now the other to face a different direction. This undertaking happens quickly, but it doesn’t lead to, or accomplish, anything beyond the doing of it. Three men lift Pernão and just as swiftly put her down again. A dancer’s slow unfolding of one leg and then another can seem more like a love note to nobody than an ordeal.

Like many sports, this piece is strenuous. The players run, leap, jump, drop to the ground, and assist one another, but there’s no sense of competition, only of strenuous, buoyant, enjoyable activity that seems to have a pattern whether or not we discern it.

Cunningham was interested in technological developments, and watching a television monitor in the Norton Owen Reading Room or exhibited in the lobby of the Doris Duke Theater, you can see “Virtual Reality,” a startling display of the process developed by Paul Kaiser and Shelley Eshkar known as “motion capture.” Joined by Marc Downie, they approached Cunningham’s solo Loops, which, late in his life, he performed only with his hands. To those hands, they attached 48 “small reflective markers” and photographed his movements from all directions with infrared cameras. In a maneuver I don’t fully understand, they then “devised algorithmic ways of interconnecting hands in both natural and cat’s cradle formations, as well as in several others.” What you see in the new version, Loops VR, is the interplay of curling and flowing, intersecting and flashing lines of colored light. Merce’s dancing hands transfigured.

In the lobby of the Ted Shawn Theater, you can also see an exhibit of Paul Taylor’s small art works and, in Blake’s Barn, a larger display of photographs and artifacts titled “Dance We Must: Another Look.” Curated by Owen and Associate Archivist Patsy Gay, it focuses on Jacob’s Pillow’s founder, Ted Shawn, his onetime wife and partner Ruth St. Denis, and their work in the 1920s and earlier. Here is the costume she wore for one of her Indian “nautch” dances. Here is the bejeweled “traje de luces” jacket he bought from a matador in Spain. Here are programs, photographs, travelling trunks, and on the wall, the immense faux-bronze image of Shiva Nataraja, poised on one foot, a lotus beneath him and an arch bearing tiny, spaced-out flames surrounding him. Look closely, and you can see how the arch comes apart and the whole thing can be fitted into the box below it.

On the walls, statements from choreographers, dramaturges, and scholars (Dr. Hari Krishnan, Lionel Popkin, Rajika Puri, Paul A. Scolari, and Gaven D. Trinidad among others) praise, criticize, and set in perspective the issue of orientalism as it developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Were the countries of the East always pleased when Westerners admired and respected their cultures? Or were they appalled by the lenses through which they were viewed?

Surrounded by all this, I forgot an important fact: Merce Cunningham would have turned 100 this year, and he is being celebrated by dance companies worldwide. If he were here, what would I say? “Happy Birthday,” I guess. And yes, oh yes: “thank you for the dances.”

.

And thank you for the post, heartfelt, clear-eyed, and a most excellent read.

We so appreciate that you took the time to comment on the exhibitions on view here this season. There’s an obvious connection between the performance you reviewed and the Merce Cunningham LOOPS installation, and the Taylor artworks are also clearly linked to our programming, while the Dance We Must exhibit is related to the Pillow in more general way. All of these offerings are embedded in the Pillow experience, yet usually overlooked by critics. Thanks for once again charting your own course, and responding in your customarily thoughtful way.

The farther we go in time the more history we accumulate and the more we need scribes to articulate it. Thanks for being there.