I am always amazed by the dances that Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker creates for her Belgium-based company, Rosas. To begin with, I’m never sure what I’ll see or where I’ll have to go in order to see one of them. Preparing to take in her Verklärte Nacht last week, I might well have wondered whether she would perform a solo, like her 1980 Violin Phase (incorporated into the four-part Fase two years later and revived at the Museum of Modern Art in 2011), or present a duet, such as her Partita 2 (2013), a collaboration with Boris Charmatz. I doubted, however, that we’d be seeing a large group piece akin to The Six Brandenburg Concertos, which made its U.S. debut in the vast Park Avenue Armory in 2018.

De Keersmaeker’s structures and her ways of re-configuring space and relating to music have always been remarkable. Vortex Temporum (2013), seen at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2016, paired each of seven dancers with one of the seven musicians in the Ictus ensemble. Wherever they were in space, you sensed their connections; you heard the dance, you saw the music.

Verklärte Nachte (2014) made its U.S. debut this past week in the Jerome Robbins Theater, a black-box space in the Baryshnikov Arts Center—so confined an arena that the three members of Rosas occasionally came within a yard of the spectators in the front row, yet so implicitly unidentifiable as a “place” that the performers’ every shift of thought or nuanced movement— clear though these were—seemed mysterious. Verklärte Nachte (originally, in 1995, a group work) lasted under an hour, and during that time, we the audience members sat as if in some kind of spiritual bondage, unable to shift in our seats or take our attention off the performers, Boštjan Antončič, Cynthia Loemij, and Igor Shyshko.

For some of us, the piece may have awakened memories of Antony Tudor’s great Pillar of Fire, created in 1942 for Ballet Theatre. That ballet was performed to the same work by Arnold Schoenberg that infuses De Keersmaeker’s Verklärte Nacht and provides its title, which translates as “Transfigured Night.” Schoenberg based his music on a poem by Richard Dehmel, a contemporary of his, that tells of a woman who, yearning for motherhood, has had a brief, ill-fated affair. But a man whom she loves and who loves her says these words: “May the child you conceived/ Be no burden to your soul.” And: “You will bear the child for me, as if it were mine.” The three principal figures in Tudor’s ballet are a desperate, repressed heroine, a kind and faithful suitor, and a sexually vibrant man who frequents a house of ill-repute across the street.

Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht, Op. 4, composed in 1899, is suffused with late-Romantic passion. At BAC, the dance is performed to a recording by two violinists, two violists, and two cellists of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Pierre Boulez. The six, sometimes five, falling notes that begin it are often repeated. Sighing, questioning, soothing, they weave into other melodies, and resurface transformed. Sometimes a single instrument calls out. The sounds may fade away at times or simply drop into silence. You’re aware of the fragility that a solitary violin can convey, the storm that the cellos boil up, and the high notes that jitter excitedly, as if the sun were suddenly coming out from behind clouds.

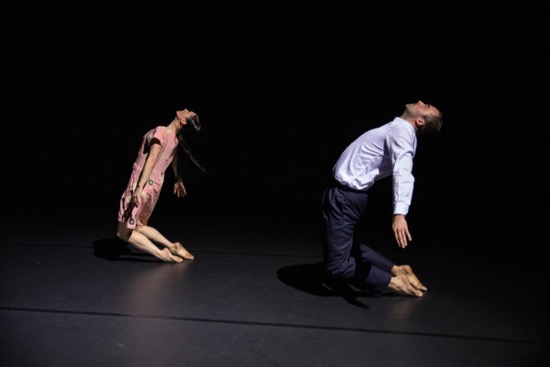

De Keersmaeker’s choreography establishes a down-to-earth formal structure. The dancers walk into the performing area from the downstage left corner and, when they’ve finished what they came for, walk out on the same path. The work begins in silence. Loemij is caught and lifted by Shyshko. When they move in unison, they might be playing a game that implies a test (“can you do this?”). But they aren’t together for long. She collapses; grasping her upper arms, he raises her slightly up from the floor and holds her there for what seems a very long time. Then they recompose themselves and walk out of sight. Almost immediately, they file in again, this time with Antončič. The men are garbed in dark suits and white shirts—no ties; Loemij wears a short, loosely fitting pink dress, spottily ornamented with flowers, plus disks that appear to contain letters of the alphabet. All three are barefoot. Now you see Antončič duplicate the way Shysko lifted Loemiji and watch both men execute Shyshko’s phrase of movement. When Loemij falls, Antončič raises her partly from the floor—just as, yet unlike how, Shyshko did this.

They exit, and this time only Loemij and Antončič re-enter. Now comes the deepest, most disturbing sequence of the work, and shortly after it begins, Schoenberg’s plangent music begins its questions. Antončič stands at the back of the area, facing away from both his partner and us on a slight diagonal. The lighting design by Luc Shaltin and De Keersmaeker creates a place that is dark around the edges, so he appears somehow distant, neutralized. Neutral? No, more like unknowable. Or standing in for an imagined person. For a long time, he doesn’t move, but I could swear that he’s listening to her.

Over and over, she approaches him from behind. Is it that she wants him to turn to her? Or that she wants to remember him, as if time has temporarily stopped? She comes up to him tentatively— sometimes so close that she could be inhaling his scent—then falls away, then tries again. And again. And again. De Keersmaeker’s choreography doesn’t call attention to itself as virtuosity—with the exception of one move of Loemij’s: she steps out onto half toe and lifts one bent leg high to the side, even as she’s falling out of this potential peak moment. She runs, tumbles silently to the floor, rolls, rises, falls. I imagine a prolonged gasp. She pulls up her dress a bit or presses it roughly down. One particular step recurs over and over, like the cries in the music. She squats low and awkwardly, feet apart, bent forward, her head hanging, and her right arm extended with the palm of her hand facing up. Her longing for something seems to have condensed into that one hand, blindly waiting for what may come. Now the music begins with its questions, its surges, its deep notes that seem to call out.

Finally Antončič turns and begins to move. Like Loemij, he can appear to be lifted and flung about by his own feelings. When he’s in the downstage right corner, he reaches offstage with one arm, but without apparent desire. The music gets fierce, even thunderous, and she races to him and jumps onto him. This is no conventional lift. Her legs are bent double and pressed against his chest. She does this more than once. The two of them dance side by side or run on a diagonal, passing each other. Sometimes he seems to snatch her out of her path. But also, when she falls into that clumsy squat, he instantly and smoothly, without stopping his own dancing, unwinds her out of it.

Briefly I wonder what has happened to Shyshko. Was he simply a brief, awkward chapter in this woman’s life?

These people are superb and nuanced movers. Loemij is close fifty years old, lean and strong, yet she conveys a frail, almost girlish sensitivity. She can be steely one moment and as boneless as a rag doll at another. No glamorous stage makeup for her. Antončič appears solidly built in his dark suit, but he’s as free in his moves as she is; like a feral lion, he can seem deceptively soft.

Suddenly, in an almost business-like way, he takes off his jacket and tosses it aside. It seems less that he’s hot and wants to cool down and more as if he’s discarding a piece of armor. He wilts slightly; she catches him. She places one hand to support his head as he begins to fall. She holds his cheeks when they’re both leaning over and all but pulls him up straighter. He can lift her horizontally, and spin with her, but he also embarks on movements that I recall her doing. When she runs one last time into that folded-up lift, he carefully pushes one of her legs down again, just before he folds up his discarded jacket. For a few minutes, they lie side by side, spoon fashion. When he arises and she stays curled up, he covers her with the jacket. But as the music becomes more and more impassioned, they roll and rise and run almost crazily. Then they “sleep” again.

In one last wild moment, she’s curled up on his shoulders. Then she quietly walks away. He revisits some of his steps, his thoughts. But on the last quiet notes of the music, he’s walking toward us. And just before he reaches us, the lights go out. Did he plan to ask us something, or was he just setting out on a voyage alone?

The audience applauds furiously, stands and cheers for the three dancers. We’ve seen an ordeal that in about an hour seems both to condense and to enrich what we ourselves may experience as, over the years, we negotiate the rigors of life. How do we approach love, how yield to it? Mysteries we expect never to solve.

good to have you back again, which enables we who do not live in the nyc area to have impressions of some of the rich dance events that happen there.

Gorgeous report.

Welcome back, Deborah, we’ve missed you. And I hope that all is well with you.

Yes, you give us a lovely window through which to imagine the performance. Glad you are writing again.

Yes, Debbie: so glad to read this poetic discussion of the piece, Really welcome back, hugs, gigi

It is amazing how much you are able to absorb and then record. A master at work. The Tudor work remains one of the most poignant and moving experiences that I have ever had in the theater due in no small part to the music which I love.. Thanks for bringing this modern take on it to life for us.