It wasn’t the usual impersonal voice reminding those of us sitting in the Joyce Theater to please turn off our cellphones, Instead, we who were waiting to see Camille A. Brown and Dancers perform her ink heard a muted, but excited babble and a voice that I took to be Brown’s delivering the requisite warning. It also might have been an invitation to see the performers as a tribe and, as much as possible, to become part of it.

She has done extensive reading and thinking about history and present reality, and no fewer than three dramaturges (Daniel Banks, Kamilah Forbes, and Talvin Wilkes) have been involved in the production. The program notes are thorough. In them, the choreographer cites the influence of two albums: Lauryn Hill’s Miseducation of Lauryn Hill and Like Water for Chocolate by Common. She wanted her dance language to have their “raw authenticity and vulnerability.” A quotation that she offers as a crucial foundation of ink comes from a book (a collection titled Question Bridge: Black Males in America): “I see black people as superheroes because we keep rising.” The dance’s six sections have to do with survival and all that the word can encompass: strength, persistence, brotherhood, sisterhood, support, courage, love.

ink (2017)is the third and final installment of a trilogy that began with Mr. TOL E. RAncE (2012) and BLACK GIRL: Linguistic Play (2015). The first dealt with elements of minstrelsy and more contemporary manifestations of racial prejudice and assigned roles; the second examined the games that schoolgirls play and the cultural roots of these. In all three, we see elements of African dance and African American variants of these. Brown evokes not only steps that could be seen on the vaudeville circuit and in Harlem ballrooms, but those practiced earlier when plantation slaves were denied drums but not forbidden to stamp and clap.

The musicians are onstage throughout the performance: Scott Patterson at the piano; Wilson R. Torres on drums; Allison Miller, percussion (and music director); and Juliette Jones, violin. They sit beneath two huge screens painted by lighting and scene designer David L. Arsenault that feature the faces of black men and women rising from a mottled surface. Occasionally the seven terrific dancers eye them. They may also gaze skyward or take a good, long look at us. These are their names: Beatrice Capote, Timothy Edwards, Catherine Foster, Juel D. Lane, Yusha-Marie Sorzano, Maleek Washington, and Brown herself.

The choreographer begins sitting on a box. In “Culture Codes,” we’re told, she is invoking Elegba, a Yoruba deity associated with opening avenues of communication and clearing spaces. We don’t “see” this in any literal way, of course. To the sounds of drumming, Brown performs a repeatable phrase that involves precise gestures; you imagine her gathering, reaping, rolling something up, stretching it out, turning small wheels. Her hands flutter, even shimmer. A lifetime codified. When she stands, the piano takes over. Now we see how fast her feet can move, keeping her low to the ground, anchoring her to a spot in space. She salutes the paintings before she goes.

Sorzano and Washington enter for “Balance,” and that’s what they achieve. They know each other’s bodies—can step out in unison or dance comfortably alone together. They face each other and “argue” in fits and starts; they hold right hands and figure out complications without letting go. Their hips and shoulders are mobile, sensual. In this loving partnership, they can stop dancing for a few seconds and brush each other off or fix each other up.

All the musicians are playing when Catherine Foster enters, wearing a draped skirt. She’s a rhythmic marvel, a champion of beauty. Unselfconsciously, she devotes herself to working up a pattern of stepping, turning, twisting her knees in what could be a frenzy were she not so in control of her wildness. (It’s a dance that Brown titled “Milkshake” and has characterized as “pattin Juba” meeting “Go Go.”) By the time Foster is finishing, only pianist-composer Patterson is still playing—slowly, sweetly.

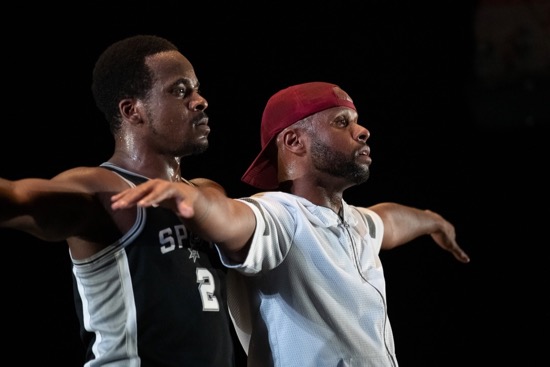

Washington enters the arena as if to establish ownership of it— jumping high, pulling himself up by the neck of his shirt. When Edwards enters wearing shorts and a red cap, the section’s title, “Turf” becomes clear. But this is no clichéd battle; it’s a compendium of what it may mean to grow up as “Black Men in America.” They back into each other as if by accident, suit up with invisible clothing (armor ?), look up in delight, sit and chat busily and silently, throw dice, dance in emphatic unison. They stare briefly at us. They also get out of breath, pat their hearts and their balls. They dance big, but also fall as if hit. Edwards digs at the ground. Someone’s grave?

In comes Lane. He’s wearing a red jacket and sneakers. Capote is ready to follow him around. “What are you doing?” one of them seems to say. (Violinist Jones has emerged from her place with the other magicians and is following the both.) He’s an athlete, can fall into a split. But when he bends way over, she puts a hand on his back and walks him along. They run in a circle together. She dances at him; then he holds her by the head—not brutally, more as if tending her, steering her. By now, they’ve removed parts of their outerwear. Maybe that’s why the section is called “Shedding,” but what they’ve dispensed with may be more significant than jackets.

Christopher Duggan

Finally the stage begins to bustle with activity, with possible violence. Everyone’s onstage. They fall, they jump and jump, until someone says “stop!” The section is called “Migration,” but these people don’t seem to be travelling to a new land. Instead, they’re excitedly working their bodies—rapidly and efficiently or sinuously and slowly. What they know of dances from the African American past has migrated into the present inventive choreography, and these together indeed acknowledge them as “superheroes.”

Afterward comes “The Dialogue.” We spectators stop cheering, sit back down and ask questions of Edwards and Washington and, eventually, of Brown and the others. Barely an hour has gone by, but a lot has happened.

What most impressed me at the performance I attended (Sunday matinee) is that the audience didn’t want to leave the theater, even after the Dialogue. They seemed to feel that this art work belonged to them–or, as one man put it, that it placed his entire family and himself, his entire life! on stage–and they basked in the glow of it. Very, very touching.

I truly, truly wish I had been there. I’m wondering if by any chance there were any questions from the audience (were there questions from the audience at all?) about this whole blackface episode in the state of Virginia? Because I would truly love to see that put into context, many contexts actually (historical, cultural, aesthetic, and racist) by an authority on all of the above, such as Camille A. Brown.