Kimberly Bartosik/daela premieres I hunger for you at Lumberyard.

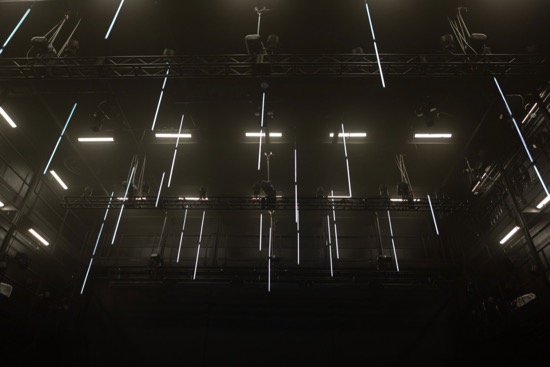

A view of Roderick Murray’s setting for I hunger for you. Photo: Alon Koppel

Lumberyard first appeared in Maryland in 2011, providing residencies for dance artists who were preparing new work. It resurfaced this past summer in stunning new quarters in Catskill, New York as a center for performances and film showings and opened its inaugural season at the end of September. On October 12 and 13, Kimberly Bartosik/daela premiered Bartosik’s new I hunger for you in Lumberyard’s state-of-the-art theater at its Water Street campus beside Caterskill Creek—a tentacle of the Hudson River—and just down the hill from the shops and restaurants of South Main Street.

The piece will have its New York City premiere on October 31 through November 3, as part of BAM Next Wave Festival, and I suspect that spectators will be seated the way we were for I hunger for you. In Lumberyard’s flexible, lofty-ceilinged black-box space, we were positioned in rows along three of its sides and hence viewed the opening sequence differently.

Christian Allen and Lindsey Jones, the first of the five remarkable dancers to enter, stand and slowly raise their arms before an array of vertically suspended neon tubes by lighting and set designer Roderick Murray. The performers (costumed by Harriet Jung in grays, browns, and blacks) face my side of the space, as do Dylan Crossman and Burr Johnson, who enter to flank them. Joanna Kotze, the last to arrive, appropriates center. So I see these five approaching us or turning to repeat their solitary paths, while those seated along the sides of the space perceive streams flowing side-to-side in both directions as they pass one another.

The pattern is symmetrical and tightly organized. At some point, I realize that Crossman and Johnson are only travelling halfway toward us before turning back. Watching these journeys, I begin to imagine them as simulating the way city streets ought to work (or, at least, how city planners think they ought to work). No one bumps into anyone else; no one gives a damn about anyone else, even though the two members of both pairs move in meticulous synchrony to the electronic background sound by Sivan Jacobovitz (arranged with Bartosik).

The movements become larger: jumps, turns, thrusts of one leg into the air, twists of the body. And by the end of the sequence, each person is making choices that differ from anyone else’s. The territory itself alters when some start taking diagnonal paths; collisions almost occur, or are avoided. Silence. Everyone calms down.

The program notes mention “deeply internalized forces of faith, violence, life force, and compassion.” Only after seeing the piece, did I read an interview in The Brooklyn Rail, during which Bartosik spoke of our current corroded political atmosphere—one in which (my words) truth is distorted, people cling to beliefs and rituals they’re unable or unwilling to examine, and reasoned dialogue is buried by violence. Every day my e-mail box is full of passionate messages calling me by name and attempting to inflame me, make me feel culpable, urge me to action, and beg for my money.

Joanna Kotze and Dylan Crossman in Kimberly Bartosik’s I hunger for you. At back: Lindsey Jones (L) and Burr Johnson. Photo: Alon Koppel

Often in I hunger for you, the dancers are locked in place, swaying or vibrating. Allen approaches each one of the others. They pay him no mind. Kotze reaches out to Crossman, who shrinks away from her possible touch; when he takes her hands and whispers something to her, she pulls away and goes toward Allen. Crossman continues convulsing. Allen and Johnson dance wildly, but that process moves them so close together that they almost kiss, almost (or do) touch cheeks. Allen slides a foot between Johnson’s legs, but in doing so bends improbably far back. Then Johnson slowly retreats, gradually raising his arms. By the time he begins to fall, Allen has raced to catch him.

Everything these people do looks both like and unlike something familiar. Crossman often crouches slightly and, knees bent, shifts from foot to foot, his hands balled into fists and pressed against his pelvic bones. What is he defending? At times, he also holds his hands low, fingers together, palms tilted slightly up, as if readying himself to push something away. Why does Johnson lift his shirt briefly to expose his belly before leaving the performing area? And where did she come from, this golden-haired child (Dahlia Bartosik-Murray), who sits down, legs crossed, and watches Kotze gesturing quietly, lost in some kind of meditation? When the lights brighten, and the sounds cease, the girl goes. Then Kotze lets her hair down, the stage darkens again, and she begins twisting and flinging her body and limbs around, as if these were all at cross-purposes. Before long, a soft throbbing sound starts up. A bit later, rumbling gives way to a perky tune.

Dylan Crossman (L) confronted by Burr Johnson. Half-hdden: Joanna Kotze. Photo: Alon Koppel

As various of the dancers come and go in this unstable world, you can believe by the way they often gaze upward that they’re searching for spiritual help. Jones, temporarily dancing alone, reaches out, as if to say, “come on, bring it on,” and for a moment, I imagine an exorcism. But another event is more purifying: Glowing between one blackout and another, Bartosik-Murray runs in a big circle over and over, light and swift. A beautiful sight.

As the music roars and develops a percussive rhythm, the five become more and more unhelpful with one another. Or rather, they try to help, but seem to have forgotten how best to do that. Still, Kotze and Johnson can join Crossman and, fists at hips, jolt in rhythm with him. Increasingly, that stance begins to convey, “I will not be moved.” You can’t always guess their intent. Crossman strokes Kotze’s face, pushes Johnson’s chest. In various ways and for unknowable reasons, people drag or lift one another.

L to R: Joanna Kotze, Dylan Crossman, and Burr Johnson in a rehearsal of I hunger for you (spectator at back). Photo: Alon Koppel.

The stage is very dim for the last section, the sound a quiet crackling. There are shadows, assertions. Crossman scours his own face and rubs a hand softly down Johnson’s face as the latter bends backward, but then strokes both his hands down Johnson’s legs as if he’d like to take the skin off them. He leaves, and Johnson remains, reaching out into space as the lights slide into blackness.

As we were stumbling out of the theater, a pleasant man we’d been talking to in the lobby before the performance, came up to us asking, “What did you think of it?” I was, as usual, politely evasive. I couldn’t say that I felt yanked about by it, astonished by its fierceness and its beauty, exhausted by it, and that “thought” was something that would come later. Perhaps ironically, after dining in Catskill and setting out for western Massachusetts, from whence we had come, flashing police lights and an accident near the eastern end of the Rip Van Winkle Bridge caused us to bear right instead of left. Driving miles south when we meant to go east, taking a vaguely familiar road and finding ourselves where we hadn’t expected to be, passing the same crossroad twice, getting little help from convenience store people, and trying to stay calm may have been a suitable follow-up to the ideas generated by the performance. Which way are we heading? What should we resist? How can we avoid violence, counter falsehood? Whom should we believe? What rituals can enlighten us, and which need to be re-examined? I don’t mean to say that these constitute Bartosik’s message, only that they crept into the creative maelstrom of her choreography and empowered it in mysterious ways.

Brilliant writing, offering, speaking of hunger, a great deal of food for thought, not just about the performance, but also if I may say so the truly terrible times in which we live. Does art heal or does it provoke, that’s one question that came to mind as I read the conclusion, putting me in the car with Jowitt and her companion just as her description of the performance as usual put me in the theater with her.