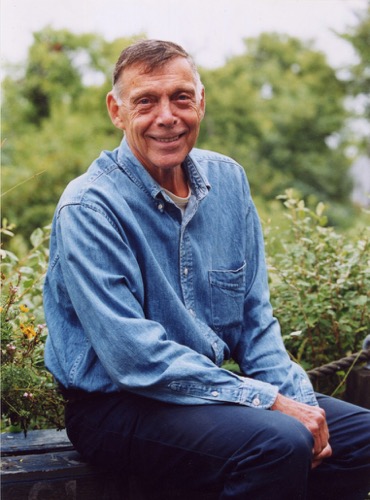

Paul Taylor in his garden. Photo: Mazine Hicks

When Paul Taylor died of renal failure on Wednesday, August 29th, and I was coping with that news, I started to think not just of the 140 dances he made during his remarkable career, but of his connection to the great figures of 20th-century dance whose pantheon he joins. As a Juilliard student, he met many of them and appeared during the American Dance Festival at Connecticut College in a piece by Doris Humphrey. In 1953-1954, he danced in Merce Cunningham’s just-founded company, and in 1954, the year in which he premiered his first work, Jack and the Beanstalk, he also played a pirate in the musical Peter Pan, choreographed by Jerome Robbins, who had understudied Humphrey’s protégée, José Limón, in the 1940 musical Keep Off the Grass. In 1959, while Taylor was a member of Martha Graham’s company (1955-1962), George Balanchine created a tie-yourself-in-knots solo for him in the 1959 Episodes, a work premiered by the New York City Ballet to music by Anton Webern that in turn offered some NYCB dancers in a companion work by Graham. Paul Taylor American Modern Dance, founded in 2015, has presented works by Humphrey, Graham, Limón, and Cunningham.

Yet in 1957, Taylor took a stance that seemed to query the physical prowess being demanded of him. Perhaps influenced by his friend John Cage’s notorious 4’33”, in which a pianist sat quietly before his instrument for that amount of time, opening and closing the keyboard cover to define sections of the piece, Taylor created seven minimal works. In one of these, Duet, he stood and a woman (Toby Glanternik) sat motionless for three minutes. Louis Horst’s review in his Dance Observer was a column of blank space headed by the title, place, and date of the performance; the venerable critic/musician hadn’t considered that standing onstage was not nothing, but rather an invitation to consider what dance was all about.

Taylor was already moving into the territory he would explore over the ensuing years. It’s a domain that juxtaposes light and dark, winging lyricism and plunges into awkwardness, refinement and crudity, complexity and simplicity, comedy and mystery. His Three Epitaphs (1956) had introduced “mourners”— clad in dark brown body suits by Robert Rauschenberg that covered their heads, hands, and feet—dancing to the raucous sounds of a New Orleans funeral band. They were both comical and somehow waifish, craving our attention. The dancers in Insects and Heroes (1961) included one disguised in a spiny black outfit—clearly an insect, but possibly heroic. Yet the 1962 program at Hunter College, where I first saw that dance, also included Aureole, set to music by Handel. It is one of Taylor’s most beautiful and long-lived works.

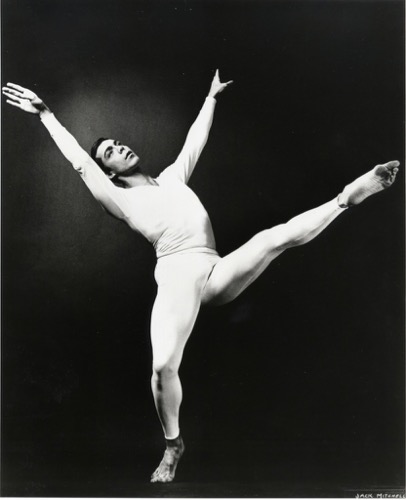

Paul Taylor in his Aureole. Courtesy of the Paul Taylor Dance Foundation Archives

I always thought that his movement style was influenced by his pre-Juilliard time at Syracuse University, where he had won an athletic scholarship as a swimmer. I’d never seen a tall, lean dancer like him move with such watery fluidity. The solo he created for himself in Aureole is a study in movement so slow and smooth that what might be difficult balances look like ongoing evolutions (others performing that solo may hint at poses; he never did). The dancers in this and others of his lyrical works, however skillful, don’t telegraph their finesse; they radiate what Martha Graham, in another context, termed “divine awkwardness.” Esplanade (1975), set to music from two of Johann Sebastian Bach’s violin concertos, is full of variations on running and walking and crawling, but its sunny atmosphere and its playful moments are challenged by a legato section in which people stand and gaze at each other or at distant horizons, touch one another tentatively, move sporadically. They look less like “dancers” than like people dancing.

For every ravishingly tender Taylor work (among them Arden Court, Roses, Eventide), there’s a stranger, darker one. Last Look (1985) comes to mind, with Alex Katz’s slanting mirrored surfaces reflecting the dancers in distortions that echo their inner anxieties and cruelties. Or Big Bertha (1970), with its spooky fairground automaton, who reduces a typical American family to its most violent urges. Or Dust (1977), with its thick black ropes hanging at one side and its dancers in the grip of some unknown epidemic.

When you see a Taylor dance, you sense a society. It may be one in which pretensions mask animal instincts, such as Cloven Kingdom (1976). Or a dance permeated by a kind of advance nostalgia for a world that is about to change, such as Sunset (1983), in which the men are garbed in soldiers’ uniforms. Taylor took pleasure in imaginatively challenging religious fanaticism (as in his 1988 Speaking in Tongues), showing traditions breaking down and in disarray. And, loving his dancers and their individual qualities, he could create a harmonious ensemble or one that foregrounded their differences.

His musical tastes were often eclectic or wedded to surprising themes. He could create a wacky world of his own or dig deep into a musical one in unpredictable ways, as he did with the tangos of his 1997 Piazzola Caldera. He could invoke an era, as he did in Company B (1991)), setting World War II images— easy-going, lusty, yet shadowed by potential death— to songs by the Andrews Sisters. But he set the seriously flawed vaudeville routines of his hilarious 2010 Also Playing to ballet music from two operas by Gaetano Donizetti.

His 1980 Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rehearsal)— twined audaciously around Vaslav Njinsky’s 1913 ballet of that name and Stravinsky’s music for it—prefaces the heroine’s sacrificial dance with a comical, two-dimensional cops-and-robbers affair. Yet, although his Beloved Renegade (2010) had been inspired by Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and the poet’s Civil War experiences in aiding the wounded, he set it to the Gloria of the deceased French composer Francis Poulenc, weaving into it visions and memories and the awareness of death. At the time, I thought that “the beloved renegade could be Taylor himself—with his eccentricities, his dark humors, his wicked wit, and the beauty he finds in innocence.”

Laura Halzack and Michael Trusnovec (dreamer and muse?) in Taylor’s Beloved Renegade. Photo: Paul B. Goode

As I write today, I imagine that those who worked with Paul Taylor over the years are sending messages to one another and congregating to recollect stories of his many creations. And not just dancers, but artists and others who collaborated with him, such as Katz and Rauschenberg, costume designer Santo Loquasto, lighting designer Jennifer Tipton, and rehearsal director Bettie de Jong. Dancer Michael Novak will now become the company’s artistic director and help carry on Taylor’s legacy.

Taylor was certainly recognized during his lifetime—not just by applauding audiences worldwide, but by awards and honorary degrees: three Guggenheim Fellowships, a MacArthur Fellowship, a Kennedy Center Honor; a Bessie Lifetime Achievement Award. And more. France made him a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1969 and over the years upped the title of knighthood to Officier and then to Commandeur. In 2000 he received the Légion d’Honneur.

He made many magnificent dances and ones less enduring. I carry a collage of them with me, remembering this atmosphere, this moment, this dancer, this feeling. I treasure two tiny artworks he gave me. They’re constructed of objects he picked up on the beach near his Long Island cottage. Smooth and splintery, combining shapes both natural and man-made, they remind me of his unique way of looking at things. He influenced me as well. One of the first dances I reviewed for the Village Voice was his Agatha’s Tale. It was 1967, and I was trying to discover what being a critic meant. Paul wrote me a letter. Knowing me as a dancer and developing choreographer, he told me that I had seen the work quite well but had then criticized what had been intentional on his part and, worst of all, cited a more experienced writer’s reaction. He closed his friendly letter with this sentence: “If you think I have sold out, then you must say so. If you think I would trade fine work for “success,” you are plain crazy and I will spank you the next time I see you.” That missive pushed me into thinking differently about my role. After all, a brisk whack can make a newborn take its first breath.

Hail and farewell, Paul. And thank you for the treasure chest of golden dances. They gave us glimpses into life’s many enigmas, its many terrors, its many delights.

Deborah, you have made me weep. And given me, eloquently, beautifully, much information I hadn’t had as you evoke the man and his work and your own relationship to both.

Even viewing this clip reminds me, as you say, of how wonderful it is when the performers do not seem to be “dancers” but rather, “people dancing.” Watching Taylor’s attention to the smallest gestures we make unconsciously in life (i.e., crossed arms and ankles) and how they can fluidly lead to some other movement, I am once again thrilled by what he left us. Thanks for the memories!

A very fine remembrance by one who bore witness to most of it. How many can lay claim to that? Deborah Jowitt, like Paul Taylor, is a very special person whose rare value should not be underestimated. Within her, dance history resides.