Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui/Eastman performs at Jacob’s Pillow

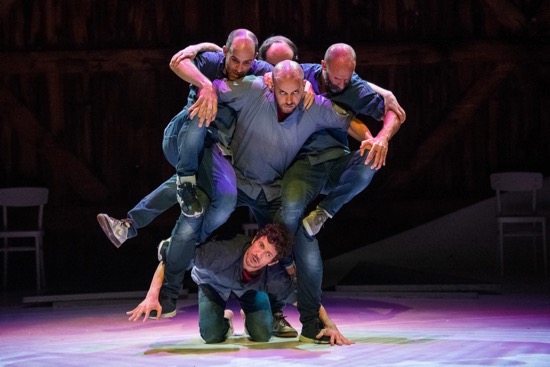

Fractus V. Patrick William Seebacher (TwoFace) supports (L to R) Johnny Lloyd, Sidi Larbi Cherkoui, and Dimitri Jourde; below: Fabian Thomé Duten. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Ten years ago, I began my review of zero degrees, the duet that Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui created and performed with Akram Khan, like this: “The audience leapt to its feet,” noting that I couldn’t remember ever seeing such an eruption before at New York City Center. Now it has happened again. When the curtain came down on Cherkaoui’s 2015 Fractus V at Jacob’s Pillow last week, the theater was smaller, but my 2008 words were still apt: “the mass of spectators—in the orchestra seats, in the balconies—rise as if a wave has rolled through the theater.”

I think this response is not to the work’s excellence alone. Several pieces by Cherkaoui that I’ve seen shape up as tests of coordination and cooperation—also as ordeals. How many times can a dancer keep doing this? What stringent rehearsing enabled this unusual feat? What if everything these people are building falls down? If a split-second timing is even slightly off, could a performer get hurt?

Often, the dancers move set pieces around—building their environment, restricting or enlarging their terrain. I think of the man-sized wooden boxes in his Sutra (2008), the silver cages, small and huge, that figured in his 2010 Babel (words), the 12-feet tall wooden folding screens of Orbo Novo (2009) that shaped a jungle gym, a maze, a prison. Two flexible faceless dummies kept Cherkaoui and Khan company in zero degrees.

The people who inhabit these dances are not always part of a consistent group headed by Cherkaoui. Sutra was performed by seventeen Buddhist monks from the Shaolin Temple in China’s Henan Province. He created Orbo Novo (which premiered at Jacob’s Pillow) for the now-defunct Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet. Babel’s dancers came from thirteen countries and spoke twenty languages or dialects thereof.

L to R: Patrick Williams Seebacher (TwoFace), Fabian Thomé Duten, Johnny Lloyd, and Soumik Datta. Photo: Christopher Duggan

The five dancers and four musicians who appear in Fractus V are billed as Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui/Eastman, an ensemble founded in 2010. Its members represent nine different nationalities. The dancers were schooled in various traditions (hip-hop, flamenco, circus, et al). Musician Soumik Data plays the North Indian sarod (held like a guitar). Shogo Yoshi plays Japanese taiko drums. Kaspy N’dia sings. Woojae Park sits on the floor to play either of two long, narrow six-string geomungos (similar to kotos). At times, the score also involves a wooden flute, a piano, and a harp. The resultant atmosphere (created by Cherkaoui and the musicians) is fascinating. N’dia’s singing can adjust to another tradition when, at one point, Fabian Thomé Duten, an expert flamenco performer, enters with elegant, stamping bravado —a passage in which he is joined by Cherkaoui, born in Belgium of Flemish and Moroccan parentage. Later, when Park also sings what sounds somewhat like flamenco cante jondo, the other four men surround Duten, doing introspective b-boying stunts on the floor and looking like fractious dogs.a

Fractus V, like many of Cherkaoui’s dances, employs text and raises political and social issues. The lines that dancer Johnny Lloyd intermittently speaks into a microphone are drawn from Noam Chomsky’s ideas about freedom of speech versus attempts by the media to control our thinking, and the movement occasionally alludes to traditions that have a ritual tang. For instance, several times during the performance, three or all five of the men line up behind one another and form what resembles a many-armed Shiva (with a difference) or create a symmetrical totem or a formalized scrimmage. During one of Lloyd’s speeches, two additional pairs of arms join the gestures he’s making in order to emphasize his words, enwrapping him and freeing him in the process.

Fractus V. (Top to Bottom): Fabian Thomé Duten, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Patrick Williams Seebacher (TwoFace), Dimitri Jourde (L), and Johnny Lloyd. Photo: Christopher Duggan

The men begin sitting at ease in chairs ranged along the back of the stage. Half the musicians are stage left, half stage right. But all of them form two squads, facing each other across the space to sing in a harmony that lifts your heart those Latin words familiar to Catholics; “sanctus” and “benedictus” rise sturdily and float heavenward.

What we see contrasts with what we are hearing (or does it?). Patrick Williams Seebacher (TwoFace) advances toward the center of the stage and performs an uncanny solo. Without moving from his spot, he quails, dissolves, entreats, sickens. All this fluidly and almost simultaneously. His opponents—one or many—are invisible; his own hands tighten about his throat. When he has finished, he watches the other four collapse, as if echoing a lesson that they’ve learned.

The men bring in and rearrange the large white triangles that make up the set (by Herman Sorgeloos and Cherkaoui), as if fitting together the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. These flat shapes create floors and walkways and poke up like icebergs. In one remarkable coup de theater, they have been arranged, peaks pointing upward in two lines that form a V; a falling dancer touches one, and they flutter down in sequence like a house of cards.

Patrick Williams Seebacher (TwoFace) and Fabian Thomé Duten “shoot” Shawn Fitzgerald Ahern. At back: Kaspy N’dia. Photo: Noor Eemaan

Cherkaoui perhaps wants us to understand that violence doesn’t conform to theatrical time. One sequence takes place between those soon-to-topple walls for so long that it becomes almost unbearable. Shawn Fitzgerald Ahern (who alternates with Dimitri Joude in this exhausting role) falls over and over—shot by three others bearing revolvers. Collapsing, flipping over, dropping like a stone, he keeps rising, will not die. And the executioners replace their guns with cameras to capture his unending demise.

Through all this the men dance wonderfully—maybe in pairs, maybe in unison. Sometimes they’re weighty, sometimes fluid (Charkaoui is as flexible as a contortionist). Often they’re contentious, occasionally deferential (they bow down to Seebacher a couple of times). When Park sings sweetly, they advance toward us, taking small steps and swinging their hips invitingly, almost an exaggerated rendition of geishas in a tea house. Krispijn Schuyesmans’ lighting throws the dancers’ enlarged shadows on a fiery cyclorama; at times, eerily, two men are moving, but only one of them has that other self. Whatever the dancers do, the musicians soothe them, incite them , force them into rhythms, and underscore their moves. The Latin title “fractus” can mean “broken” or “weakened” or “defeated.” A percussive crack at a certain moment can make you imagine a bone shattering.

Charkaoui has written that “Fractus V stands for the natural fractures which are necessary to grow and become stronger.” You can think of that in many ways: as the knowledge that healing transmits to the body, the torture of supposed heretics that promises them a place in heaven, or the revolutions against an existing order that hope for an improved society.

Another great review at a time of fracture. Let the healing begin.

It never cesases to amaze me how many art expressions can be done with body movements. I have to say that the title got my attention, and very fitting for a great article.