The Martha Graham Dance Company at New York City Center, April 11 through 14

Martha Graham’s Embattled Garden. Left: Lorenzo Pagano; right: Anne O’Donnell and Lloyd Knight. Photo: Melissa Sherwood

I assume that Isamu Noguchi heard at least some of Carlos Surinach’s sly, scorching music for Martha Graham’s Embattled Garden in rehearsal before he designed the scenery that would be so crucial to the 1958 dance. The garden is the one we’re told existed in Eden. No greenery for Noguchi (and not much innocence in the behavior Graham created). He created instead a low, gaudily colored platform with a hole in its middle; you could imagine it as a conversation pit were it not for the slim flexible poles that edge it and suggest rushes that the dancers need to push through. The other structure is a tree whose parallel branches resemble a giant comb. Jean Rosenthal’s lighting, re-imagined by Beverly Emmons, casts a hot, unshadowed sun on the landscape.

Embattled Garden was the first dance on the Martha Graham Dance Company’s 2018 opening gala at City Center, the oldest piece, the only one by her on the program, and the only one to focus on character and struggle. Compared to her 1940 El Penitente, with its tempting and its apple, this is a sensual, hot-wired essay into. . . .what? Wife-swapping gone temporarily wrong? The muscular, sinuous Stranger (Lorenzo Pagano) can hang upside down from the “tree” like the snake that he is. He can connive with Lilith (Leslie Andrea Williams), Adam’s first wife according to Hebraic folklore. Adam (Lloyd Knight) is still as guiltily attracted to her as the Stranger is to Eve (Anne O’Donnell).

Leslie Andrea Williams and Lorenzo Pagano in Embattled Garden. Photo: Melissa Sherwood

Graham suavely constructed this quartet to display the shifting allegiances. It’s Lilith who binds the hair Eve has been lashing around, and Adam, standing behind Eve where she sits, who strokes that ponytail up his chest as if it were his proudest possession. The four may, late in the dance, stand in a circle on the platform and bow formally to one another—arms open and slightly bent, hands cupped, fingers together, but that may be a pretense.

The bright colors of the set, the hints of a fiesta in the music, Lilith’s yellow dress and red fan and Eve’s red gown are in keeping with the uxoriousness and marital discord that Graham created. She shows the Stranger tempting Eve (falling onto her in fact), Lilith lying on the floor, opening and shutting her legs as Adam stands over her, Adam wrestling with his two-edged lust, the men fighting fiercely, Eve letting rage invade a tender duet with Adam (whap! she slaps him hard). Graham’s choreography manages all this with formal clarity. Figures freeze while others move, yet keep their motivations alive. In the end, Adam falls into Eve’s lap, but recovers to lift her up and carry her to “their” platform. He’s stroking that long hair again as the curtain falls.

O’Donnell, Williams, Knight, and Pagano perform their roles in this vivid quartet superbly—always aware or who’s doing/feeling what in this cocktail party pared to its possible savage essence.

Anne Souder and Lloyd Knight in Lucinda Childs’ Histoire. Photo: Melissa Sherwood

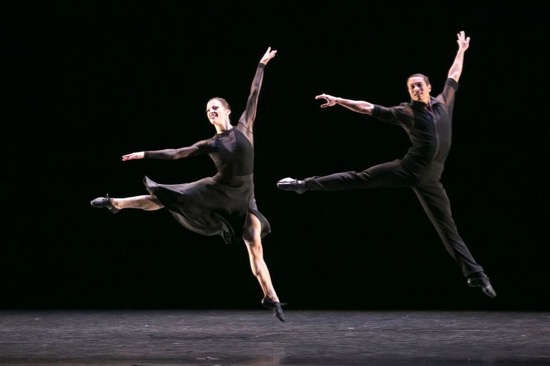

Lucinda Childs created a duet, Histoire, for the Graham company’s 1999 season. For the 2018 season, she developed it into a dance for four couples. The original piece, performed by Lauren Dalley Smith and Ari Mayzick, is set to Kzrysztof Knittel’s Histoire III, and the dance is cooler than the music and, following Embattled Garden without an intermission, it calms us down.

Smith and Mayzick wear black (costumes by Karen Young) and black shoes. And to Knittel’s initially meandering music for harpsichord and tape, they advance toward and away from each other on a diagonal path, changing places, examining one another. By the time a high-toned percussive beat pushes its way in, they’re ready to dance in unison. The movement is balletic in some ways (a leg lifted high in arabesque, say), but the two also cover ground in easy-going skips that don’t aim for height. They end as they began, and three other paired performers enter: Lloyd Mayor, Marzia Memoli, Ben Schultz, Anne Souder, Knight, and O’Donnell.

Laurel Dalley Smith and Ari Mayzick in Lucinda Childs’ Histoire III. Photo: Melissa Sherwood

Now the music is Piazzola’s Milonga en re for violin, piano, and double bass, followed by his Soledad for violin, bandoneon, piano, and double bass. So the temperature heats up a bit, along with Yi-Chun Chen’s lighting. Some of the motifs hint at relationships within the formality. For instance, couples stand, spaced out on the stage, the men facing the back and the women attempting to peer around them toward us; then the men push their partners away. The piece is a mini-feast of identical duets on an imagined ballroom floor.

The Martha Graham Company in Lar Lubovitch’s The Legend of Ten. (L to R): Lorenzo Pagano, Ben Schultz, Laurel Dalley Smith, Anne Souder, AbdielJacobsen, Charlotte Landreau and Ari Mayzick. Photo: Melissa Sherwood

At City Center on opening night, Lar Lubovitch’s 2010 The Legend of Ten was preceded by a ceremony. The Graham company’s artistic director Janet Eilber presented Lubovitch with an award honoring his remarkable fifty-year choreographic career. As she told the audience, he has made dances not just for his own company, but for ballet companies worldwide, as well as contributing to operas, musicals, and ice skating productions and competitions. He’s daring musically too: The Legend of Ten is set to the first and fourth movements of Johannes Brahms’s Quintet for Piano and Strings in F minor, Op. 34, as recorded by a young Glenn Gould and the Montreal String Quartet. Lubovitch says in a program note that he used the “ten dancers as the legend mapping the musical and emotional textures of the music.”

The piece (staged by Katarzyna Skarpetowska and Reid Bartelme) starts with the dancers—one or a few at a time—rushing onto the stage and stopping dead, almost aggressively, but almost immediately they erupt into a flurry of movement—expressing themselves individually and/or falling into unison with others. You feel, as you often do with Lubovitch’s works, currents that rise and fall as the dancing flows on. But within that, there’s a sense of breath, an upward arc of movement that the dancers suspend before falling softly away from it. Often as they do this, they hold one curving arm overhead, a gesture that emphasizes the suspension.

Charlotte Landreau (center) and members of the Martha Graham Dance Company in Lar Lubovitch’s The Legend of Ten. Photo: Melissa Sherwood

Lubovitch wants us, I think, to be aware of individual agency. Now and then, amid a moving cluster of dancers, one drops out of the pattern and acknowledges the audience and her colleagues with the smallest of bows before being reabsorbed into the group. At first, there are only nine people onstage (So Young An, Abdiel Jacobsen, and Charlotte Landreau are the only ones not already mentioned). They run smoothly into patterns: parallel lines, circles, curves within curves.

Souder appears as a loner, and everyone watches as Jacobsen takes her in his arms and lifts her. Is she returning to a village she knows? You can imagine that. She fits right in. After a while, with Jack Mehler’s lighting quieting down and the music calm (although played at gratingly loud volume), the two of them drop to the floor to begin a duet. Their arms and legs entangle in unusual ways; the feeling is tender—and they indulge in it lavishly, sensuously—yet not erotic in any obvious way.

As they leave the stage, the others re-enter from an upstage corner and travel slowly along a diagonal. They’re bent over, flinging out one hand rhythmically, as if sowing seeds. This last movement has the air of a peasant celebration. The performers thrust their fists into the air, dance with their legs wide apart, hold hands in a ring. As impeccably as the choreography is structured, it still has a sense of folks roistering, with the two “lovers” periodically affirming their unity within the community.

I am eager to see this dance again. The Martha Graham Dance Company will perform it this coming week during the Lar Lubovitch Company’s season at the Joyce Theater. The dancers, splendid as they are, don’t yet look fully at home as they make the transitions from one fluid, surging pattern to another. That romance-infused torrent that Brahms created in the 19th century takes no prisoners.

April is an important month in the life of the Martha Graham Company. In that month in 1926, Graham and her trio of young women made their debut on a New York stage. In that month in 1991, she died at the age of 98. Long may she live.