Merce Cunningham’s Sounddance at the Juilliard School. Foreground: Anca Putin held by Thomas A. Woodman. At back (L to R): Mikaela Kelly, Matthew Gilmore, Eoin Robinson (hidden), and Kalyn Berg. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Watching the Juilliard School’s annual Spring Dances, I think of young racehorses turned loose on a course. The Juilliard performers aren’t as young as those ballet dancers who join companies while still in high school; after four years at the school, they’ll graduate with BFAs. However, all that they’ve learned, and are still learning, is on the line in these performances, and often, they’re being shown in choreographic masterpieces. In their careers-to-come, how many of them will have a chance to appear in Merce Cunningham’s 1975 Sounddance or Twyla Tharp’s 1973 Deuce Coupe IV, or even in Crystal Pite’s more recent Grace Engine (2012)? The contrast between these works on this spring’s programs is so marked that just watching the pieces (each is double cast), the student dancers surely get a jolt of education.

Watching Sounddance, as staged by Jean Freebury, is like attending a three-ring circus in the stratosphere. Mark Lancaster’s set is an immense, intricately draped gold curtain, and to begin the show, Eoin Robinson (in Cunningham’s role) spins through a gap in its center, a ringmaster who doesn’t hesitate to intervene. The other nine dancers in the cast that I saw arrive one by one, or two at a time, until all ten are onstage. (Here comes Kalyn Berg. Now Anca Putin. . .what a jump!). Some arrive late. To David Tudor’s wild, unsettled Untitled (1975-1994), manipulated by Trevor Bumgarner, they race through encounters—distracted here, pulled there. This being a dance by Cunningham, their torsos are usually erect, their legs turned out and lifted high, their toes pointed. But their composure is easily disarranged.

Merce Cunningham’s Sounddance. Foreground: Peter Farrow lifting Mikaela Kelly. On floor: Madison Hicks prone on Matthew Gilmore. Behind them (L to R): Miranda-Ming Quinn atop Eoin Robinson, Anca Putin, Thomas A. Woodman. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Sometimes I stop thinking “circus” and think “construction site,” with all its delays and speed-throughs. Six people may join together in unison or four start jumping. One man grasps the hands of two others, braces himself, and holds them firmly, while they, bent over, jitter their feet in place. A woman is lifted, straight and doll-like. Another woman gets hoisted by two guys as if she were a plank needing to be put down somewhere else. The most complex, cooperative tangles dissolve before you know it, and there are always at least three things happening to draw your eyes.

The dancing never stops. In the end, the dancers peel off from it and disappear behind the gold curtain: one, then another, then another, as if being sucked away. The last person onstage (Robinson) exits rapidly and without fanfare. The show’s over. I once learned that shortly before Cunningham created Sounddance, he had been given a microscope and was enthralled by the wiggling organisms it revealed. Circus, construction site, lives too tiny to see with the naked eye? Call it a great dance.

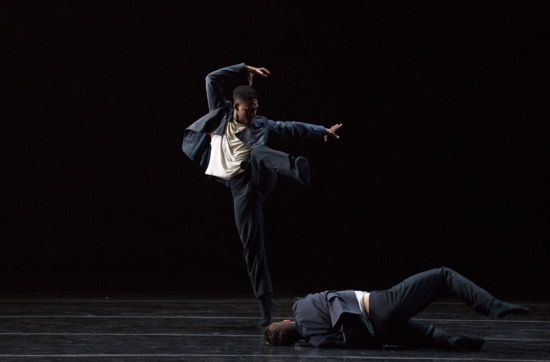

Jared Brown (jumping) and Barry Gans in Crystal Pite’s Grace Engine. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Pite choreographed Grace Engine in 2012 for Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet, once a part of New York’s dance scene, and Alexandra Damiani staged it for Juilliard. The piece shows, to some degree, the influence of Pite’s acknowledged mentor, William Forsythe. Its dark, violent world may excite you, but you’re glad (at least I am) not to be a part of it. Sometimes, the fifteen dancers unify in some way, but more often it’s hard to tell whether they’re instigating mayhem or fleeing it. Wearing black shoes, black trousers, and unbuttoned black jackets designed by Nancy Haeyung Bae, they race into and through this very dangerous place, as if hurled there by strong winds or inner turbulence.

In the beginning, Jim French’s lighting design consists of a line of overhead lamps at one side of the stage, stretching from the front to the back. This changes, of course (at times, lights flash), but it sets the disorienting mood, as does the appearance of a single dancer (Alex Soulliere), whose footsteps across the stage are amplified to an ominous degree. From time to time, a dancer opens his/her mouth in a silent howl or forms a hand into claws. Much of the time, they’re low to the ground, hunkered down, legs wide apart; they could be jockeying for position in a football game. Or fighting the air around them. If they push off the ground, it’s the landing you notice. They skid across the floor, drop as if shot, roll or scrabble along, rebound, and race away or into tangles with others; one person may shove another out of the way, then wrench someone else around. More disturbingly, they often put one hand on a colleague’s head to pull or push that temporary victim.

Paige Borowski (L) and Hannah Park in Crystal Pite’s Grace Engine. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Owen Belton’s score is a pulsing repetition of loud sounds that increase the intimations of peril. Goaded by it and the nature of the movement, the Juilliard dancers perform full-throttle—marvelous in their commitment to this maelstrom. After a while, one of the men peels off his jacket and tosses it into the wings; the other guys follow suit.

Pite, however, has a fine sense of when to simplify what we see; one dancer (Hannah Park for instance) or two (Mykal Stromile and Naya Lovell, say) or four spend some time onstage. Once, they form a chain in profile to us, each with a hand on the person ahead of her/him. When they’re affixed like this, a movement rippling down the line affects each of them differently, but pushes all off balance. Individuals may pull away or fall or explode out of the formation, but they always return. At some point, they pass one of the women (Paige Borowski, I think) down a line. In the end, a single dancer, staring into the distance, is left alone. Who knows what’ll happen to her?

This isn’t the first time that Juilliard students have performed Deuce Coupe. William Whitener, who danced in the original version, staged it for Juilliard in 2007. By then it had already been altered. When I saw the work in 1973, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. It was the first piece that Tharp had set on a ballet company, and not every dancer in the Joffrey Ballet was sold on it immediately. Tharp put herself and her dancers into it as well. Actual graffiti artists spray-painted a backdrop while the dance unfurled. I remembering reading (or hearing?) that when the Beach Boys saw this work that Tharp had set to their recorded songs, they cried. They were that moved.

What was surprising back then was that Tharp’s approach to ballet made the piece look as fluent as the style she had developed in such dances as her 1971 Eight Jelly Rolls and The Bix Pieces. I loved Deuce Coupe II (the version edited by Tharp for the Joffrey dancers alone) much less. Still, its offspring, Deuce Coupe IV, is exhilarating in its shrugged-off complexities and requires an uncommon versatility from the performers. The only cavil I have with some of the Juilliard dancers in this staging by ex-Tharpist Richard Colton is that they have trouble being cool in something so demanding.

Foreground: Katerina Eng in Twyla Tharp’s Deuce Coupe. Behind her (L to R): John Hewitt, Libby Faber, Alexander Sargent, Mio Ishikawa and Lúa Mayenco Cardenal (both hidden), Myles Hunter, Zoe Hollinshead, Cassidy Spaedt Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

The piece begins with three people dancing to a piano version of “Cuddle Up” arranged by David Horowitz. A woman and a man (Taylor Massa and Sean Lammer in the cast I saw) begin working together quietly in the shadow of Katerina Eng, who will appear frequently as a reminder that ballet is a thing of beauty, Dressed in white, forming the familiar shapes, she’s alone among the many, and if she needs a moment by herself simply to rotate slowly balanced on one leg, we appreciate the concentration and strength that maneuver involves.

Then the Beach Boys’ “Little Deuce Coupe” kicks in and the cast enters slinkily, one at a time from downstage left. The increasingly long line snakes from left to right, traveling upstage as it goes. We’re seeing the reverse the “Kingdom of the Shades” procession that opens Act IV of of Marius Petipa’s 1877 ballet La Bayadère! These dancers, however, are no ghosts in white tutus. Their attire riffs off Scott Barrie’s originals: knee-length orange dresses for the women, red pants and Hawaian shirts for the men. And everyone in the cast attacks this parade and the dozen or so songs to come as if they were appetizing courses in a banquet.

Tharp ingeniously probed different rhythmic and stylistic elements from the songs, drawing the sweetness out of one, getting clumsy with another. The words, too, provide thematic touches. “How She Bugalooed It” incites rascally zest. Zoe Hollinshead and Myles Hunter have disputatious fun with “Shut Up/Go Home.” “Alley Oop” brings out the apish instincts of Mio Ishikawa, Lúa Mayenco Cardenal, Kolton Krouse, Alexander Sargent and Benjamin Simoens; spraddle-legged, bent-kneed walks are one way to get around. In “To Catch a Wave,” Libby Faber, Kylie James, Myles Hunter, Nicolas Noguera, and Hollinshead run and skid across the stage, legs frozen mid-stride. Cassidy Spaedt soloes in “Got to Know the Woman.” Massa and Lammer get together again in “Mama Says.” Everything slides or edges into what follows, eluding Big Statements. And Deuce Coupe ends with “Cuddle Up”— its first words, “The night has come,” issuing in an anthem to tenderness. Individuals join an ongoing dance, each finding his/her own occasion to fit in, until all are doing the same steps, united.

Some people in the audience may never have seen Deuce Coupe before. As I watch these talented dancers nudging their way into its complexities, I can’t help viewing it as a palimpsest through which I glimpse earlier versions and end up—even as I applaud the Juilliard dancers’ zest and diligence—wishing that Twyla Tharp still maintained a company of her own. How they once bugalooed it!