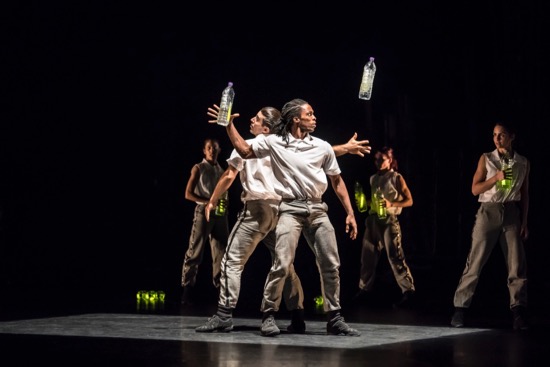

Members of Acosta Danza in Goyo Montero’s Alrededor no hay nada tossing Yanelis Godoy. Photo: Andrew Lang

Some of us may remember Carlos Acosta, when he was appearing with England’s Royal Ballet or, more briefly, as a guest artist with American Ballet Theatre. Princely. Virtuosic. He performed with other major companies as well. But he returned to Cuba, the country where he was born and nurtured. There he established the Carlos Acosta International Dance Foundation and, in 2015, his own company, Acosta Danza.

The repertory that the ensemble brought to New York, after performing in England, Germany, Austria, and Turkey, balances Cuban roots with international adventures. Three of the choreographers—Goyo Montero, Marianela Boán, and Raúl Reinoso are Cuban. Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui is Flemish Moroccan.

What’s remarkable about the fourteen dancers on view during the group’s U.S. debut at New York City Center, as part of its Adelante Cuba! Festival, is the intensity of their focus at every moment. It’s difficult to pinpoint this quality of living in the instant, but your eyes are always drawn to a performer who has it. And even quite a few celebrated dancers do not have it. Interestingly, one of the five choreographers represented, Jorge Crecis, got a PhD in London, and, according to his program bio, created a “methodology for training and replicating higher states of consciousness and peak performance.”

Jorge Crecis’ Twelve (Carlos Luis Blanco foreground). Photo: Johan Persson

Crecis’ work, Twelve, which closed the program, attests to his success at this. A dozen dancers share the stage with about four times that many green bottles that glow in the light (lighting by Michael Mannion and Warren Letton, adapted by Pedro Benitez). To muscular music by Vincent Lamagna, Reinoso picks some from a box and hurls them, one by one, at his colleagues, who arrange them in various patterns, while throwing themselves into the air and onto the ground. What’s been carefully calculated begins to look exhilaratingly spontaneous. Bottles fly across the stage. How could this person downstage left predict how another person far away on stage right could angle and time a throw so that it bypassed efforts by others? These artists can field and toss bottles while sitting on another artist’s shoulders as well. The dance resembles a strenuous game whose rules you can’t fathom, but one at which all these men and women are astonishingly expert. The audience laughs and gasps, and on the second night of the season, during the entire duration of Twelve, only one bottle fell to the floor. Picture what rehearsals must have been like.

A threesome in Goyo Montero’s Alrededor no hay nada. Photo: Andrew Lang

Montero’s Alrededor no hay nada, a work for eleven dancers that opened the evening, is equally demanding, but very different. The title can be translated as Everywhere There is Nothing or Nothing Everywhere or Everywhere: Nothing. The score consists of poems or songs, either by Joaquin Sabina or Vinicius De Moraes, with the spoken or sung sequences set off by silences. I’ve forgotten most of the Spanish I knew, so I catch only certain words and phrases, like two days of the week (“sabado” and “domingo”) repeated in a litany of sorts, or “el día de la creación” mated with Genesis.

Five male-female pairs are lined up at the back of the stage as the piece begins, rocking in their embraces, as identical as a string of mirror images. These individuals also express themselves as no strangers to ferocity. They crouch like animals about to spring. One of two men, later manipulating a woman, presses his hand over her face. Four men push a woman around. Four women step over a fallen man as if he were a discarded object. They all cluster to toss one of them (Yanelis Godoy, I believe) into the air. Whatever games this finely organized society is up to, they have a bleak aspect.

Men and women are equally strong, though, and, especially when they wear hats and dress alike (garments are discarded and put back on over the course of the work), not easy to tell apart. The piece is not entirely without humor. Once they band together to create a bizarre image of the magician’s trick of sawing a woman in half: two lines of dancers support two women who are hidden horizontally between them; one’s head sticks out, the other’s feet, so we imagine a woman with a five-foot-long body. After the dancers have bowed graciously to our applause, they back up and race toward us vaulting into the air. It’s as if they’re saying, “Here we are. Take a look. We’re yours for the evening.” And they are.

Marta Ortega and Carlos Acosta in Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s Mermaid. Photo: Johan Persson

Three male-female duets nest between these two group pieces. The first, Cherkaoui’s Mermaid, is perhaps the most enigmatic, partly because of Fabiana Piccioli’s atmospheric lighting, with tent-shaped projections of rays or showers and the smoke that pours onto the stage. Wearing a silky red dress, Marta Ortega is as fluid and slippery as a mermaid, but the stemmed glass in her hand suggests that another kind of liquid is affecting her. She does, however, seem like an alien creature to Acosta (performing as a guest artist in his own company). Supporting her as she attempts to balance, he gazes now at her face, now at her feet (she’s wearing pointe shoes). He also takes her glass away and sets it down offstage.

Words spoken in, I believe, Korean seep into the music by Cherkaoui and Woojae Park, as do singing voices. Ortega becomes insect-like. She’s standing on her head when Acosta, who has left the stage for some reason, returns to clutch her. She squiggles offstage, leaving him to move his arms sinuously and make turns in the air look as if he were groping for a solution. When she reappears, she’s barefoot and steps as if rediscovering her feet. A thread of water streams down at the back of the stage, and he fills the glass with it and gives it to her. As I said, a strange piece, beautifully performed. A mermaid prepares to live on land with her lover; a woman in love renounces her addiction, and pure water ousts gin.

Carlos Luis Blanco (L) and Alejandro Silva in one cast of El Cruce sobre el Niágara. Photo: Johan Persson

The most intense of the duets, Boán’s El Cruce sobre el Niágara (Crossing Niagara), takes its title from a play by Alonzo Alegría. The play imagines the famous 19th-century tightrope walker, Blondin, who crossed Niagara Falls in complicated ways—this time carrying a man (his manager!) on his back. Boán has been inspired to recreate this act as a relationship that must be perfectly balanced, two united as one, in order to succeed. The fine line suspended above disaster becomes a metaphor. In the cast I saw, Reinoso, wearing only a jockstrap, slowly, smoothly, carefully advances along a diagonal in a restless landscape of music by Olivier Messaien. He treads that narrow track— sometimes on tiptoe, sometimes balancing on one foot; standing in an arabesque, he slowly bends his standing leg without even the hint of a quiver. It seems to take him forever to reach solid ground at the downstage right corner of the stage, where a figure lies curled up on its side. Awakened, this sleeper, Mario Sergio Elias (also nearly naked) takes his place on the virtual tightrope, and the two begin a voyage together.

Boán has taken the historic image of two men bonded for their dangerous walk into something less specific. Yes, one lifts the other, yes they once wobble and shake slightly, but more compelling is their journey as equals. Pressed or hinged together, intently focused, their bodies glistening, they step lightly in fastidious unison, conveying not just the image of a daring passage, but something more sensual. In the end, in a sudden blue atmosphere (lighting by Carlos Repilado), Reinoso lifts Elias and travels in a circle, at the same time slowly revolving. No wonder an amber floor spotlight illumines them and red light rains down from above.

Marta Ortega and Raúl Reinoso in an earlier cast of Reinoso’s Nosotros. Photo: Yuris Nórido

Reinoso ventured into choreography as recently as 2014. His duet, Nosotros (Us), projects fondness and quiet sadness and ends with a question. Laura Rodriguez (in the cast I saw) wears a red suit that bares her legs and red socks; Javier Rojas is garbed in black trunks and black socks. The accompanying music by José Victor Gavilondo Peón is also a duet, he playing the cello and Cicely Parnas the piano. Light also plays a role in this relationship. A bright pool of it suddenly appears, and, as if it constitutes a danger, Rojas pulls his partner out of it. Their socks suggest that they’re adventuring on slippery terrain. They cling together. In the end, she walks away, but turns her head toward us, and for a second, before the stage goes dark, only her face is lit.

After this, the marvelously intrepid performers start throwing those bottles, and when they’ve finished Twelve, the audience cheers for them. Acosta Danza is planning to present new works by two highly diverse choreographers, Saburo Teshigarawa and Pontus Lidberg. I should imagine these dancers are up for anything they can devise.