Jane Comfort & Company Revisit Forty Years of Work

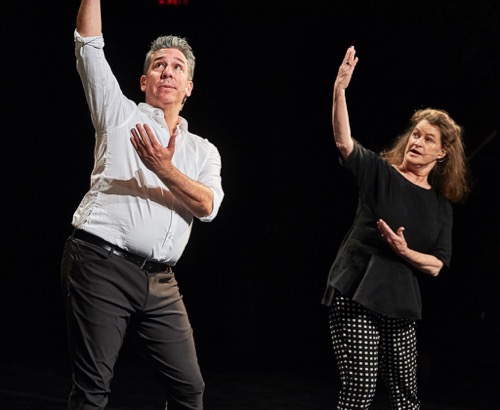

Heather Christian and David Neumann in Jane Comfort’s Faith Healing. Photo: Robert Altman

In 1978, Jane Comfort and I were both forty years younger. Not a surprise? I guess not. But that sentence may prove a snappier lead than my starting off by recounting what Comfort has accomplished over those forty years and how many dances of hers I’ve seen. (See how I snuck the facts into my non-lead? Or should I spell it “lede” as did the editors of The Village Voice, in which I once wrote my reviews?).

Jane Comfort and Company’s 40th Anniversary Retrospective of in La MaMa’s Ellen Stewart Theatre was everything such a performance ought to be. Excerpts from eight dances, a starry roster of original cast members, newcomers, film clips, slides! All these slipped behind, together, and to the side of one another. All splendidly lit by Joe Levasseur. Filmed moments of Comfort herself, reminiscing close-up and at ease in her Soho loft, bridged gaps and introduced the excavated material. She (live) also introduced her husband John, son Gardiner, and daughter, Claire (applause), since they had lived through many of those years of rehearsals. There was wine afterward.

The works—shown in chronological order, along with memories and images of others—bespeak Comfort’s ongoing discomfort with gender and racial inequality, political chicanery, secrecy, hypocrisy, and more. Not many choreographers tackle Barbie dolls and what they convey (Beauty, 2012), extradition of suspects to places where interrogations allow torture is allowed (American Rendition, 2008), governmental hearings (S/He, 1995). None, I suspect, would reimagine the two candidates in Clinton vs. Dole election as bunraku puppets with visible handlers (Three Bagatelles for the Righteous, 1996). Few choreographers approach such hot subjects with Comfort’s imaginative juxtapositions, an unflinching gaze, and a pungent sense of humor.

Peter Sciscioli and Jane Comfort in her Four Screaming Women. Photo: Robert Altman

Comfort introduces the retrospective with an excerpt from For the Spider Woman. Filmed by Neelon Crawford in 1979-80, it shows her dancing the same steps as her pregnancy progresses. With a belly about ready to discharge its inmate, she’s still going strong. She also appears live with Peter Sciscioli to begin her 1982 Four Screaming Women (already making a gender comment). This piece knocks home a stylistic choice she uses often and wonderfully well in her early work: the connection—or disconnection—between language and gesture. The two performers, standing side by side, link each mundane question and response or comment to a gesture or an in-place move. Words, such as “Is that what you want?” and “Be sure,” are repeated rhythmically over and over in shifting patterns, gradually introducing new word-plus-gesture elements (“Did you vote?” is one) Pretty soon, Nancy Alfaro and Leslie Cuyjet join them, and immaculate unison develops.

Javier Perez and Cori Marquis in Jane Comfort’s Street Talk. Photo: Robert Altman

Auchee Lee, the original percussionist for Street Talk (commissioned by Creach/Koester in 1984), is on hand to create a simmer on his tablas beneath the duet that’s being performed face to face by Cori Marquis and Javier Perez. The two, their hands like paws, keep not-quite punching each other, sneaking in a kick now and then, or a softer touch. No hostility, just a kind of gabble in which neither of them is for sure hearing the other.

Comfort drew the text for her Faith Healing (1992) from Tennessee Williams’s play The Glass Menagerie. In this excerpt, shy Laura (Heather Christian) has a conversation with the Gentleman Caller (David Neumann in his original role!). He, a bit awkwardly, begins to copy her gestures as a way of getting to know her. Before this, however, he appears as her dream date, Superman, and against a film of clouds scudding over a blue sky, they race ecstatically around the space (in 1992 the pair roller-skated) and, belly down on two stools, arms wide, they fly.

Mark Dendy (L) and David Neumann in Jane Comfort’s Faith Healing. Photo: Robert Altman

Mark Dendy poignantly revisits his original role as Amanda, Laura’s mother, after Sean Donovan (he and Cuyjet are co-directors of this retrospective masterminded by Comfort) repositions the stools and covers them to create a love seat (he’s the exasperated, mostly offstage son, Tom). And Dendy, dreaming aloud of better days, in the southern accent Comfort grew up knowing, talks of parties and gentlemen callers that Amanda has known.

In one interlude, Comfort mentions Diane Torr and her Drag Queen workshops of the 1990s (how to sit on the subway like a guy, for instance, taking up more than one seat with legs spread to show the bulge). Comfort participated in that workshop and, in male attire and character, joined its participants in a bar, maintaining the disguise. A heady moment. A filmed excerpt of Comfort’s 1995 S/He, with her in that role and André Shoals gorgeous in wig and evening gown, ends with the two matter-of factly stripping down to their underwear to reveal the gender into which they were born.

Jane Comfort’s S/He. Foreground: Sean Donovan (L) and Nancy Alfaro. At back (L to R): Stephanie McKay, Edisa Weeks, Leslie Cuyjet, and Christina Redd. Photo: Robert Altman

Appalled by the 1991 Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill hearings, in which the Supreme Court nominee was exonerated of sexually abusive conduct and Hill, his one-time assistant and victim, was embarrassed, talked down to, and vilified by the Senate Judiciary Committee, Comfort borrowed elements of that text for S/He and used both gender reversal and racial reversal as a strategy. In the LaMaMa performance, Donovan plays “Mr. Hill” and Alfaro assumes her original role as “Miss Thomas.” The senators are marvelous vocalists and mean movers; their harmonies and their rhythms make the inquisition deadly, but also reduce it to the charade that it was. These white males are embodied by four powerhouse black women: Cuyjet and (from the original cast) Stephanie McKay, Christina Redd, and Edisa Weeks.

Jane Comfort’s Underground River. ((L to R): Leslie Cuyjet, Cynthia Svigals, Petra van Noort, and Sean Donovan flying Basil Twist’s puppet. Photo: Robert Altman

The post-intermission half of the evening follows Comfort’s career from 1995 to 2016.I felt a little sorry for those in this 2018 crowd who didn’t see Underground River, even though they delighted in seeing Cuyjet, Donovan, and Petra Van Noort join original cast member Cynthia Svigals in manipulating with slender little sticks Basil Twist’s foot-high puppet made only of strips of white sheeting. While the four chant, how gaily and proficiently he/she dances, leaps, soars before being laid to rest! What not everyone may have known was that the original piece’s audio told of a child in a coma, with parental voices urging her just to blink an eye to show she heard them. Just blink? The four performers embodying her collaborated on complex feats to show just how impossible that tiny task might be for her. The puppet, originally and miraculously put together onstage by the performers, represents her departing spirit.

Asphalt by Jane Comfort. Javier Perez (L) and Julius Hollingsworth. Photo: Robert Altman

I wrote about Comfort’s dramatic 2002 Asphalt, but that week the then-editor of the Village Voice pre-empted the dance review page for a feature article, and my review was never published. I had told of the homeless young DJ Racine unwillingly descending into the hell of his origins, “an abandoned city house, where the ghosts of Racine’s family swirl from the cracks like music from the vinyl platters he spins.” In the LaMaMa excerpt from this two-act drama with music by Toshi Reagon and text by Carl Hancock Rux, these ghosts accumulate as a support group behind Perez. When he falls back, Christian, Cuyjet, Donovan, Paul Hamilton, Redd, and original cast members Julius Hollingsworth, McKay, Nunley, and Svigals are there to support him; when he should move forward, they’re behind him; they rock him, lead him. Alfaro and Sciscioli join in the singing; McKaye sings alone and marvelously.

Jane Comfort’s Altiplano. Foreground: Cori Marquis (L) and Gabrielle Revlock. Behind them (L to R): Petra van Noort, Javier Perez, and Paul Hamilton. Photo: Robert Altman

Guided by Comfort (now filmed in a car with her son), the evening moves from narrative into plotless but not entirely undramatic terrain: Altiplano (2015). Its atmosphere suggests the high desert, its denizens and its winds. Van Noort dancing some of Comfort’s big, loose, yet precise movements, conjures up mysteries. She, Cuyjet, Donovan, Perez, Gabrielle Revlock, and Darrin Wright are original cast members; Hamilton and Brandon Washington are newcomers. Garbed by Liz Prince in costumes with tiny traces of glitter, they dance to music by Brandon Wolcott. Amid their comings and goings and Comfort’s expertly designed three-part counterpoint, Cuyjet and Donovan face off, like two wary creatures trying to figure out whether they can be mates or not; he reaches to touch her; she reacts as if to a small shock. That testing, too, becomes part of a pattern.

You Are Here (2016) returns Comfort to the city and its mostly orderly congestion. Right-angled paths, near collisions, pedestrians locked into their own missions, but often gazing skyward beyond the buildings that dwarf them. A six are members of the original cast: Hamilton, Marquis, Perez, Revlock, van Noort, and Wright (who solos wonderfully and ends spinning wildly, knocked from the required equilibrium). A hat is placed atop a mic stand, and the words “border wall” are heard.

The entire cast of Jane Comfort’s 40th Anniversary retrospective in Amazing Grace (Comfort right of center in deep pink shirt). Photo: Robert Altman

At the end of You Are Here in 2016, a legion of people, folk of all ages, gradually rose from the audience and joined the cast. In 2018, on the night I attended, a token few did so. But every single cast member fed into the growing assembly (as directed by Luke Miller) and joined a meaningful if enigmatic pattern of small gestures. You could interpret one of these as throwing something over the shoulder to get rid of it, another as opening the arms wide to welcome what’s to come; other hand movements suggest tasks, doubts, common goals. Within the sound score devised by Comfort, we hear “Amazing Grace.” Indeed.

Happy 40th. Congratulations. Thank you.

Having seen Jane Comfort’s 40th anniversary performance and reading your blog, I can’t help but wonder why you mentioned Nancy Alfaro and Mark Dendy in passing. These two performers among others in the original company were a great source of inspiration to Ms. Comfort’s work. Ms. Alfaro’s voice is still amazing as was Mr. Dendy’s delivery. Is agism being perpetrated by the aging as well??

Leslie Journet wishes that I had praised Mark Dendy and Nancy Alfaro more strongly. I can’t argue with that; they deserve to be honored. Her remark about the ageing (me) possibly perpetrating ageism brought home the narrow line we writers walk in relation to calling attention to performers’ age, as if the fact that they’re still going strong were the most remarkable thing about them. Damned if I mention it; damned if I don’t. I’ll give it more thought.