The Stephen Petronio Company performs new and historic works.

Nicholas Sciscione in Stephen Petronio’s Wild Wild World. Photo: Robert Altman

It has long been something of a tradition that so-called modern dancers forge their own styles, train those who perform their works, and, inevitably, appear as a central power onstage. However, New Yorkers attending Paul Taylor’s recent American Modern Dance season were treated to guest artists performing works by Isadora Duncan and Trisha Brown, as well as commissioned works for the company by others. This past week, the Stephen Petronio Company performed Merce Cunningham’s 1970 Signals, as part of Petronio’s five-year Bloodlines project. Staged by former Cunningham company members Rashaun Mitchell and Melissa Toogood, it’s the second Mercian work that Petronio has revived: Rainforest (1968) appeared in the repertory in 2015.

Signals is a spare, yet witty and oddly convivial work. The six dancers wear loosely fitted body suits in pale colors, with binding wrapping their limbs intermittently. Several hard-backed chairs are available for them to lounge on while waiting to enter the dance or taking a rest. The chairs can be repositioned wherever they’re desired. Richard Nelson designed the lighting.The music is supplied by Paula Matthusen, Ron Kulvila, and Margaret Anne Schedel of Composers Inside Electronics, who are stationed before their equipment at the front of the Joyce Theater.

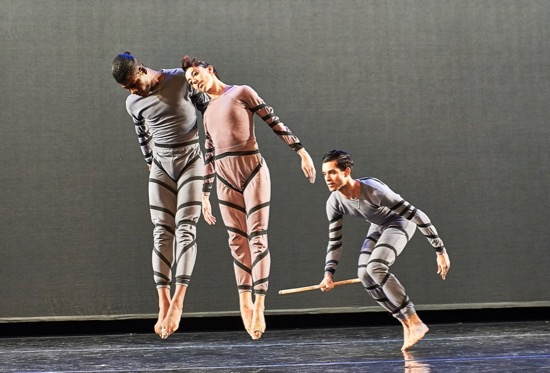

Merce Cunningham’s Signals: Elijah Laurant and Jaqlin Medlock jumping, Ernesto Breton wielding the stick. Photo: Robert Altman

Many of the movements are familiar; you see them in other Cunningham works. Sometimes the dancers travel sideways, kicking an occasional leg high. Facing us to do this, they are as flat as if pressed between two invisible panes of glass. Like ballet dancers, they establish their verticality, chests lifted, gaze steady. And, of course, they also perform moves that upset that serenity, that confidence, and our expectations. Nicholas Sciscione, for instance, partners Tess Montoya by turning and raising his knife-straight legs while seated, giving her barriers to negotiate. All six dancers (Bria Bacon, Ernesto Breton, Elijah Laurant, Montoya, Jaqlin Medlock, and Sciscione) are adept at little fast-footed steps and slow balances, their rhythms nuanced as they worm and dart in and out of the music’s delicate moments and sudden explosions. You may hold your breath while one of them, Montoya, inches into a full turn while planted on one foot and holding her other leg high to the side.

The past inevitably seeps through the present. When Breton, assuming Cunningham’s role, thrusts a stick in various ways into a close-knit duet between Laurant and Medlock, I don’t see a master choreographer measuring their strategies, but a fine third person playing a serious game. There are other kinds of games on view, since Signals has indeterminate aspects. Where and how a chair is moved may send a signal, and when the dancers line up side by side and hold up various numbers of fingers, peering to see who presents what, that action may instigate something. When they band together to dance in unison, the clamorous music can’t supply a pulse, so Breton vocally gasps out the cues.

Stephen Petronio’s Wild Wild World. Foreground: Megan Wright and Miriam Gabriel; restrained at back: Ernesto Breton

When these dancers (plus Miriam Gabriel, Ryan Pliss, Mac Twining, Megan Wright, and guest artist Joshua Tuason) leave Cunningham’s choreographic world and enter Petronio’s via Wild Wild World, they get, in a sense, roughed up—and by that I don’t mean they’re inexact. The title for this excerpt from the evening-long 2003 Underland, comes from Nick Cave’s recorded score; those are some of the first words we hear intoned. And Sciscione, alone and dancing furiously (and magnificently) at the beginning, is wearing one of Tara Subkoff’s costumes that looks as if something or someone has ripped it.

In fact, all the dancers appear to have dressed for a strange party in dark, subtly glittery clothes, and bits of Cave’s songs of death, disaster, and possible redemption emerge through a soundscape of elements sampled and manipulated by Tony Cohen, as well as through Ken Tabachnick’s dramatic lighting. Is it my imagination, or does the theater suddenly become colder? Regardless of what we know to be the truth—that these superb dancers are in full control of their movements—these people might be being tossed about in a maelstrom. Since they’re almost never limp, their straight, scything arms and legs can—almost—make them look like puppets. I think not just of weather gone crazy, but of architecture exploding.

The Stephen Petronio Company in his Hardness 10. Ernesto Breton (kneeling), Megan Wright and Nicholas Sciscione supporting Tess Montoya; Jaqlin Medlock; and (rounding the corner) Elijah Laurant. At back: Liam Byrne. Photo: Robert Altman

The title of Petronio’s brand new work, Hardness 10, made me think about the power of his dancers. But he has explained in a video (https://vimeo.com/259378338) that he was referring to diamonds, which rate a 10 (the highest number on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness). You can think of them as originally embedded in rock; the excess must be cast off and the jewel shaped. I wouldn’t deny that his dancers are such jewels, both the men and the women are paragons of strength and clarity. But not everything is hard-edged about the dance. Musician Liam Byrne sits atop a platform to play Nico Muhly’s composition on his viola da gamba, although I believe that some of the other sounds we hear are recorded. And the seven dancers’ costumes both confuse and emphasize the image we have of them. Patricia Field ARTFASHION has costumed them in outfits that have been hand painted by Iris Bonner/These Pink Lips (several dancers spot bright pink lipstick). Phrases and sentences circle the performers’ bodies and limbs: black letters on orange costumes, white letters on dark blue ones. One costume, for example, reads “Look, don’t touch” and repetitions thereof. A strip of lights high on the back wall—just one element in Tabachnick’s design— projects toward us, as well as down onto the stage.

Stephen Petronio’s Hardness 10. Bria Bacon dancing and (L to R): Nicholas Sciscione. Elijah Laurant, Jaqlin Medlock, Megan Wright, Tess Montoya, and Ernesto Breton. Behind them: musician Liam Byrne. Photo: Robert Altman

The dancers begin in a phalanx, simply walking on clear paths—say, on a diagonal from one corner of the stage to its opposite. They’re focused, but matter-of-fact, and in no hurry at first. It’s intriguing to see how that theme alters. Occasionally, individuals burst out of the pattern for a few seconds of individual expression, but it’s as a unit that they occasionally wilt slightly and twist back, as if in aversion, without breaking their rhythm. A group may become two groups with differing plans. Eventually the pace may speed up. Once we get used to the walking, we see it everywhere—as if someone must always be walking, whether that’s actually true or not.

Nuggets of other kinds of dancing are not so paired down. Bacon and Laurant run onto the stage holding hands. Three people tangle, while others walk away. The four women take over the stage and partner one another handily. The three men become a unit. Diamonds can scratch a hard substance like glass, but there’s no conflict in Hardness 10 between walking and the more complex activities. Each has its own facets, its own ways of shining.

Deborah: mistress of metaphor! Many thanks for vivid review and once again putting me in the theater with you.