Paul Taylor American Modern Dance at Lincoln Center through March 25th.

The Paul Taylor Dance Company in Doug Varone’s Half Life. Photo: Paul B. Goode

I think I finally got it straight: Paul Taylor American Modern Dance is a presenting organization and the Paul Taylor Dance Company is one of the organizations it presents and for which it commissions new work. (There. That wasn’t hard, was it?) During its ongoing season at Lincoln Center’s former New York State Theater, PTAMD in collaboration with the American Dance Festival in Durham, North Carolina is presenting a program titled Icons. On it, Sara Mearns, a superb principal dancer with New York City Ballet, performs an assemblage of Isadora Duncan’s solos; members of the Trisha Brown Dance Company appear in her 1983 Set and Reset, and Taylor’s own company dances his own iconic Esplanade (1975). Doug Varone’s new Half Life, on the other hand, was commissioned for the Paul Taylor Dance Company, in part by the Harkness Foundation for Dance.

It’s always fascinating to see Taylor dancers, grown wise in his style, attack another choreographer’s work. In a program essay by Robert Johnson, Varone said his goal with the dancers was “getting them to be the energy, rather than be people creating the energy.” Of course, they are the people creating the energy, but the point, I think, is that you can’t discern what they want. Where are they going when they race offstage, and coming from when they return?

Doug Varone’s Half Life. Paul Taylor’s dancers (L to R): Sean Mahoney, Eran Bugge, Parisa Khobdeh, Heather McGinley, and George Smallwood. Photo: Paul B. Goode

The stage is their grim playground. They rush on and off, cluster, form an occasional line. They collapse, hurtle to the ground, roll, spring up. Collisions are inevitable. A few movements appear again and again: shrugging a shoulder, as if to get something off it, or raising palms in a manner that suggests, “back off” or “leave me alone.” This is indeed a half life—an endless cycle of one person pushing another away in passing, or yanking another off the floor and maybe into an uncomfortable relationship, or shoving into a space within the group. These twelve people, dressed by Liz Prince in shades of blue and purple clothes that don’t look “designed,” thrust their way through Varone’s scrimmages, never finding an unobstructed way to live. They fall into a line stretching from the front of the stage to the back, as if sucked there, but within seconds, the line is fractured by their individual tantrums.

You can follow one dancer for a while. Parisa Khobdeh’s long lashing black hair catches your attention, or Michael Trusnovec’s expert way of avoiding collisions. Eran Bugge may be lifted high. Pauses occur. Julia Wolfe’s score, played by the Orchestra of St. Luke’s and conducted by David La Marche, batters against the performer, falls silent, rises in pitch, drops into a deep shaking. Lighting designer James F. Ingalls overhangs the stage with horizontal rows of lights—one at first, the rest accumulating until they form a bright, harsh ceiling. In the end, the white backcloth slowly puddles down to the floor, and the rows of lights begin to descend too, flickering as they go.

Paul Taylor’s Mercuric Tidings: Michael Trusnovec and Laura Halzack. Photo: Paul B. Goode

This program began with Taylor’s gentle, fragrant 1985 Roses and ended with his 1982 Mercuric Tidings. Mercuric indeed! Jamie Rae Walker, Michael Apuzzo, Christina Lynch Markham, and Madelyn Ho got a rest after Roses, but Michelle Fleet, Khobdeh, Michael Novak, Heather McGinley, George Smallwood, Lee Duveneck, and Alex Clayton spent intermission wiping off the sweat, fixing their hair, and getting into Gene Moore’s pink outfits (the men bare-chested) for another kind of fray. James Samson replaced Trusnovec. I’m telling you all their names, because Mercuric Tidings is also a killer work, if a happier one. Excerpts from Franz Schubert’s first and second symphonies set the valiant performers jumping, leaping, skittering, skipping, and hitting their legs together mid-air. Encyclopedias tell of the planet Mercury’s eccentric orbit and the tidal forces that influence, and perhaps Taylor was once interested in such matters. I, however, cherish his way with what appear to be human eccentricities. Fleet, for instance, seems to be a kind of governess to the other women—now joining them in their unison dances and hand-in-hand lines, now standing off to one side scrutinizing them, making sure they frame or orbit—but don’t bother— Halzack and Samson’s exuberant lovemaking.

I have no idea how Taylor chooses the works he extracts from the annals of modern dance, but Isadora Duncan’s early solos and Trisha Brown’s Set and Reset share one quality: free flow. Although Duncan drew her imagery from Pre-Raphaelite paintings and ancient Greek statues, she moved through their poses—a free spirit in her semi-transparent tunics. Her sense of nature and the natural were a surprise to dance audiences of the early twentieth century. The dancers in Set and Reset, one of the works Brown categorized as “unstable molecular structures,” don’t reassure your eyes with positions. Movement travels circuitously through their bodies and streams from their fingertips and softly flung up legs. Duncan is heroic, as well as a sensuous wanderer in imagined wind and water, with the music of Romantic composers to buoy her up. Those performing Brown’s choreography execute extraordinary movement with everyday demeanor, taking pleasure in the task, but not dramatizing it.

Sara Mearns in Isadora Duncan’s “Narcissus” waltz. Photo: Darial Sneed

Lori Belilove, the director of the Isadora Dance Foundation and Company, created an anthology of Duncan solos and coached Mearns in them. She herself learned these from her early studies with two of Duncan’s six adopted daughters, Anna and Irma, and from their immediate generation of pupils. Of the ten short dances in this suite, seven are set to piano pieces by Frederick Chopin, two to waltzes by Johannes Brahms, and one to Franz Lizst’s Les Funerailles. Belilove’s choices, beginning with Chopin’s Prelude, Op. 28, No. 4, move from a blissful anticipation to love and wilder or darker aspects of life.

The only things that marred the suite slightly for me were a less than graceful coral tunic that Mearns wore and an odd little platform on which she began and didn’t use again. One musical selection was taken at a speed that I think Isadora would have avoided. However, these are minor quibbles. Mearns has always been able to endow her ballet roles with a certain earthiness when that is desirable, and channeling Duncan, she uses that pliant sense of weight with increasing confidence as the suite progresses. She has learned that Duncan’s joyous skips often skimmed the earth rather than escaping its pull and that when she lifted her arms to the heavens, they seemed to hold a generous offering.

A gleaming grand piano sits at one side of the stage, and Cameron Grant, the New York City Ballet’s masterful pianist, plays the music marvelously. Mearns occasionally alludes to him when the choreography brings her close to the piano. Occasionally, she exits, and he plays on, or the lights go out. The dances that she performs—barefoot, of course—may involve a scarf or a dark-colored overdress or rose petals grasped and scattered, and the moods shift subtly, as does Rob Brown’s lighting design. At some point, a dark backcloth descends.

Mearns may perform seated, as she does in Chopin’s “Narcissus” Waltz (Op. 64, No. 2), or reclining. Mazurkas bring out the boldness or the gaiety in her, especially the one subtitled “Gypsy” (Op. 68, No. 2). Others are steeped in melancholy. True to Isadora’s spirit, she seems sometimes to see something offstage or above her—something to implore, cherish, or flee—but Mearns performs these moments with admirable restraint. The two Brahms waltzes are particularly poignant, following, as they do, the deep, shuddering tones and somber mood of Les Funerailles. They come from a period when Duncan was in love, and love’s tempestuous aspect is expressed in Op. 13, No. 14 and its lulling sweetness in the familiar No. 15. Mearns, her long hair flying, her body in tune with the music and the style, deserves her standing ovation.

An earlier cast of Trisha Brown’s dancers in her Set and Reset. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Despite my words about flow, Set and Reset begins with a sharply outlined image that I have always thought of as a witty goodbye to what Brown called her “equipment pieces.” Three of the six dancers carry a fourth overhead. She’s lying on her side, flat as a board, and appearing to walk along invisible walls. Her position and our view of her echo Brown’s 1971 Walking on the Wall, in which dancers mounted ladders, hooked themselves into halters on ropes, and, attached to tracks mounted on the ceiling of the Whitney Museum, journeyed along a gallery’s two walls.

That’s the piece’s most enduring stable image. Everything else in it flickers: the black-and-white newspaper images in the Robert Rauschenberg collages that are projected onto three three-dimensional structures; the fluttering, translucent Rauschenberg costumes imprinted with the same kind of images; and the tall, transparent curtains flanking the stage’s wings, which occasionally billow in the wind of the entrances and exits. We see the dancers through a scrim as they cross from one side of the stage to another. Before the structures rise to hang above the dancing, their constantly shifting collages and the voices in Laurie Anderson’s “Long Time No See” constitute an overture that wakes up our eyes for what is to come.

Rauschenberg also collaborated with Beverly Emmons in designing the lighting that illuminates the dancers who perform Set and Reset. The fine current cast comprises Cecily Campbell, Marc Crousillat, Kimberly Fulmer, Leah Ives, Jamie Scott, and Sam Wentz. Their collisions and near collisions happen as if impelled by an uncertain breeze. Unison, as when Ives and Scott (as I recall), briefly dance the same steps, is rare. The organism that the dancer form and reconstitute is as flexible as their bodies and the complex ripples of movement that pass through them. Such beauty!

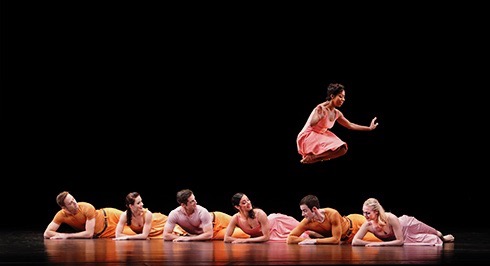

Paul Taylor’s Esplanade. Michelle Fleet jumps over (L to R): James Sansom, Eran Bugge, Michael Apuzzo, Parisa Khobdeh, Robert Kleinendorst, and Jamie Rae Walker. Photo: Paul B. Goode

It seemed to me that some members of the current cast of Esplanade perform it as if they loved it too much. But nothing can detract from the almost risky glee that Taylor built into this 1975 work, set to sections of two of J.S. Bach’s violin concertos: women launching themselves into the air and across distances to be caught by partners at the last minute; people skidding across the floor and plunging down to it. If you look carefully, you may notice that most of the steps are smartened up versions of what we do every day: walk forward and backward at various speeds, crawl on our hands and knees, run, fall, roll over, jump to avoid a puddle. The dance is an icon in terms of Taylor’s genius, but it touches something basic that we all understand in our own bodies, which is also true of Duncan’s transformed simplicity.

Am reading your review in Melbourne, a world under, and am enjoying your connecting me to the spirits of America.