Dana Reitz premieres Latitude at New York Live Arts

Dana Reitz in her Latitude. Photo: Kate Enman

“Exquisite.” That was what a colleague whispered to me as he emerged from New York Live Arts’ theater into the lobby. Maybe he spoke quietly because Dana Reitz’s trio, Latitude (the third and last presentation of the annual LUMBERYARD in the City festival), had attuned us to every nuance of sound and how it impinges on silence. That single shared word was enough. A gush of them would have been distracting.

Some of the people watching Latitude at its Friday night performance could, like me, remember solos Reitz created in the 1970s and performed unforgettably; others may have seen Necessary Weather, a duet by Reitz and Sara Rudner in 1994, and another generation of viewers possibly attended its Baryshnikov Center revival in 2011. You might be old enough to have seen Reitz dancing alone in Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach in 1976, or have been twenty years younger when she and Mikhail Baryshnikov toured a program together.

Reitz has been a Professor of Dance at Bennington College since 1994. Elena Demyanenko is on the faculty too. The third member of the cast, Yanan Yu, is an MFA Teaching Fellow at that Vermont institution, where in 1930s summers, Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey made dances and ate breakfast together. The three women range in background as well as in age: Reitz grew up in the United States, Demyanenko in Russia, Yu in mainland China.

Lighting has always been a crucial partner in Reitz’s work, whether she worked with theatrical designer Jennifer Tipton or visual artist James Turrell. She herself designed the lighting for Latitude, with Rick Martin as supervisor and consultant. Its intensity, direction, and quality alter how we perceive the women. Four parallel, horizontal paths of light with one rounded end appear at times on the stage floor; at other times, only individual ones of these are lit. A glow may descend from a single high lamp. Once, Reitz, moving alone, has her shadow as a burden. Occasionally the whole stage suddenly becomes a glaringly bright place, but other changes of atmosphere occur slowly and subtly.

Dana Reitz’s Latitude. (L to R): Reitz, Yanan Yu, and Elena Demyanenko. Photo: Kate Enman

In the past, Reitz has used compositional strategies that give the performer choices within a structure (improvisation is too broad a term and has resonances that I suspect she would rather avoid). The word “choreography” doesn’t appear in the program listings either. Demanyenko, and Yu are credited with contributing “Movement Material.” The title, Latitude, can imply room to move around in a given situation, as well as a geographic measurement.

The three of them, costumed by Charles Schoonmaker in warm, muted colors, keep close track of one another much of the time; when one is dancing, the other two stand or sit near the dark edges of the stage, watching their colleague. You get the impression of shared tasks being modulated in various ways, but you don’t ask yourself, “What are they doing?” What they are doing doesn’t get the building built or the princess wed; best not to linger on such thoughts should they occur. An insert in the program by Melanie George warns us, “There are no problems to solve or outcomes to report.”

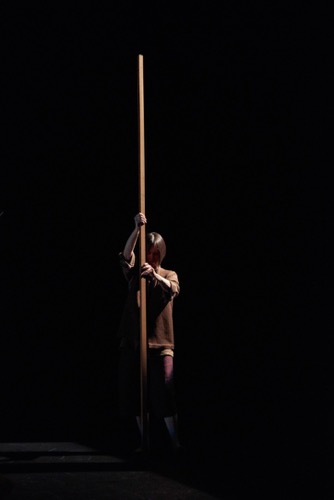

The silence itself is mesmerizing. Even the audience is still. Did I hear one person cough over the course of an hour or so? Two? This quiet means that we not only hear the sound of slim poles—four in all—when a performer clatters some together on the floor or strikes a pole’s end against it, we also hear the faint whisper of wood on marley when Yu draws one pole slowly and gently into a new place. Demyanenko, dancing alone, eventually emits a groan, then something a bit stronger. A few times, the three cluster together and consult one another in voices too soft for us to make out the words.

Yanan Yu in Dana Reitz’s Latitude. Photo: Kate Enman

Maybe the pole designs map something we can’t fathom. The objects themselves can suggest tools (Yu takes one in either hand to push a third one across the space) or pointers; when holding them horizontally at chest level, the dancers may fleetingly make you think of tightrope walkers. Movement and lighting unite to alter the terrain. When the three performers crawl on all fours across the space (a rare moment of near unison), an invisible ceiling has lowered. When they spread apart, they appear to draw the space out with them; now it’s larger.

Much of the movement is simply walking, as the performers carry out their tasks, but when it’s complex, it seems to allude to atmospheric changes or interior ones. A woman may be looking in one direction while her body swivels elsewhere. Very delicate adjustments may be followed by a strong, sudden one, or vice versa. I wonder at how Demyanenko reaches her elbows behind her, straining slightly even as she focuses on something else. Reitz’s arms fluently sketch things on the air, twist it, shape it. One of the women may raise her hands as if to mean, “back off!” or to push against a barrier, but she performs the gesture without emphasis or dramatic intent.

Elena Demyanenko in Dana Reitz’s Latitude. Photo: Kate Enman

Everything that happens in this small, beautiful world matters at the moment you watch it, and although the fastidiously crafted piece moves forward in a little over an hour, you don’t think about climax or outcome. Once, near the end, Reitz and Yu hold their poles horizontally and charge toward each until they clash, then back up and try it again. They let us see that the process amuses them mildly, but there’s no “outcome,” no “champion.” The ending of Latitude isn’t conclusive either. The three are gathered together again, turned away from us, quietly talking something over, until the slowly dimming lights make them vanish.