David Dorfman Dance at BAM Harvey Theater, November 8-11.

David Dorfman Dance in Dorfman’s Aroundtown. (L to R): Aya Wilson, Jasmine Hearn, Nik Owens, Jordan Demetrius Lloyd. Simon Thomas-Train, and Kendra Portier. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

I came home Wednesday night wanting to crawl into bed with David Dorfman’s Aroundtown, snuggle up to it, and have better dreams. You understand, of course, that I don’t mean that literally; six dancers, four musicians, plus Dorfman and his wife (guest performer Lisa Race) wouldn’t fit in my bed. But the hour-long piece that I’d seen at BAM Harvey (a BAM commission and a New York premiere) stirred up such strong feelings—about love and friendship, about anger that seethes up under everyday good manners, about tenderness, about cooperation, about hope —that I wanted to hug it to me.

Designer Oana Botez has costumed the terrific performers as the motley bunch that they are: Jasmine Hearn, Jordan Demetrius Lloyd, Nik Owens, Kendra Portier, Simon Thomas-Train, Aya Wilson. The men wear casual clothes in bright colors and patterns, but you might not want to go around town in the women’s attire. Wilson’s plaid skirt is only two different-length pieces of one; Hearn’s orange dress has no back; Portier’s skirt no front. Equivocal attire you might say.

The projected framed scene above them initially shows a snowy night and a spreading, bare-limbed, painted tree (Shawn Hove, media designer). But there’s nothing wintry in how these people dance. The floor might as well be rubber. Together they run, leap and skip in many ways, turn and fall, get up and do it all over again. They’re interrupted when singer Liz de Lise enters, and Dorfman and Race arrive to greet her like the hosts that they are and to assist her in walking over the backs of the now-kneeling dancers until she reaches her place on the platform, where she joins guitarists Sam Crawford and Zeb Gould, saxophone player Jeff Hudgins, and Dorfman, who provides percussion. De Lise composed three of the five songs she sings, as well as collaborating with Crawford on another. Gould wrote one too.

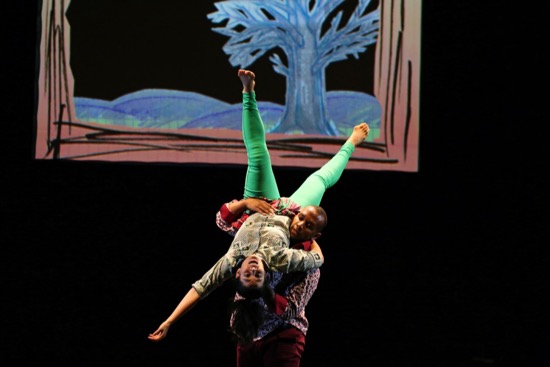

Nik Owens holding Aya Wilson in David Dorfman’s Aroundtown. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Over the course of Aroundtown, formality brings order, then crumbles, then brings the dancers together again: several times they face one another in two lines of three, their arms open wide or their hands clapping brisk rhythms. Violence occurs in dreamlike slow motion—mouths open in a silent yell, fists knocking jaws askew, bodies crumpling, hands reaching out (we see it up close too, in video images projected where the tree had been). But, when the performers are done with that kind of dissent, they smile, walk into a different configuration, and straighten out their disheveled garments

The music supports them, roughs them up, soothes them, and falls silent while they rethink. It turns jazzy for a brief, warm duet by Wilson and Owens. I try to pay attention to the words of the song, “Take What You Want,” but have to catch them on the fly. Some of lighting designer Tuce Yasak’s instruments are part of the decor; a double line of them climbs vertically, then right-angles across the top of the back wall. Near the beginning, lights glare at us, dim down, glare again.

These dancers are nimble—earthy yet springy. Their handsome, strenuous dancing turns the stage into an adult playground. Their legs may straighten and their feet point, but they seem malleable—as if their strength has been softened a little by heat. They don’t try to show you beautiful body designs; they flow and burst through their moves, making the resilient choreography look like something they could do everyday on a smaller scale. Spinning a bunch of times is nothing—a cup of coffee to start the day, a moment to unclog the brain.

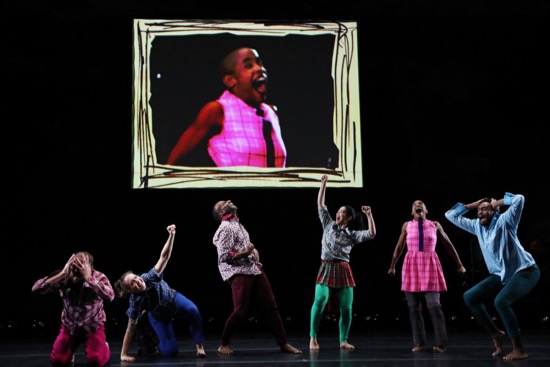

Members of David Dorfman Dance in Aroundtown. (L to R): Aya Wilson, Jasmine Hearn, Jordan Demetrius Lloyd, Kendra Portier, Simon Thomas-Train, and (hidden) Nik Owens. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Dorfman is marvelous at organizing collaborations in meaningful, even emotionally stirring ways. At one point, Lloyd is followed and encircled as he spins about; when he falls and lies supine, the clustered group lifts Portier and tips her down so she can give him a kiss; then another takes her place and does the same thing; then another. (I wonder later if this refers to the song “Baby Bird”).

When the group as a whole connects and freezes into a tableau, Portier yanks at them, trying to move the whole assembly elsewhere. No luck. Finally she succeeds. Then she backs off and, calling out “Here comes love!” races to them and is lifted high. She likes this so much that she cries “again!” and does it three more times. The fourth time, they toss her into the air. The last time, she runs, but they’ve all gone and she falls. “This won’t be my last day. . .” Is that what sweet-voiced de Lise is singing? Then all the others return and take their places in those pacifying lines—refrains that provide breathing time and re-dedication between ordeals.

Jasmine Hearn projected above (L to R): Simon Thomas-Train, Kendra Portier, Nik Owens, Aya Wilson, Hearn, and Jordan Demetrius Lloyd. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

These dancers are accomplished actors as well. The house lights come on, and Hearn walks toward the front of the stage, telling us, “I see you.” She’s quite charming, makes us think that we have something in common with her, that we “match” her. Then, smiling, she says, “I’m in hate with you.” A few seconds later, she’s having a screaming fit—hating us and letting us know it.

Thomas-Train has an outburst that starts out with a stifled memory. He mentions a church. No, there was no church. “There’s always a church.” He remembers himself and his two brothers, bored, throwing rocks at each other. But he begins to have trouble saying what he means. The others try to help. “Take me around.” They oblige. Next: “I don’t want you around.” They go. Silence. Then in one of Aroundtowns’s many complete changes of mood, he asks if we want to hear the joke about two whales going into a bar; it’s a terrible joke, but Lloyd is willing to stand beside him and be his patsy.

I should mention that the projected landscape changes. Sometimes it shows what appears to be a clumsy map, marking pockets of green that might be islands in a dry land. At other times, we see a church dwarfed by pines and pointed hills. Or the familiar tree looking beleaguered.

The final image of David Dorfman’s Aroundtown. (L to R): Aya Wilson, Jordan Demetrius Lloyd, Simon Thomas-Train supporting Nik Owens, Jasmine Hearn (hidden), and Kendra Portier. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

In the end, Portier tidies Thomas-Train up, and they begin a quiet duet; so, in counterpoint, do Dorfman and Race. The latter two are decades older, and perhaps we’re supposed to see this as a memory, as well as an affirmation. Our final images, however, are of the group reprising a few of their earlier ideas. We hear, “I will wait for you.” They’ve lifted Owens high, and from his perch, his sweet, high voice rings out: “I will wait on you forever.”

In time of trouble, it’s imperative to fight usefully, to cuddle up to those you love, and keep dancing, however thin the ice you stand on. Is that Dorfman’s message or just mine?